Recent Articles

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS and the Cost of Passion: SPIELBERG SUMMER Continues!

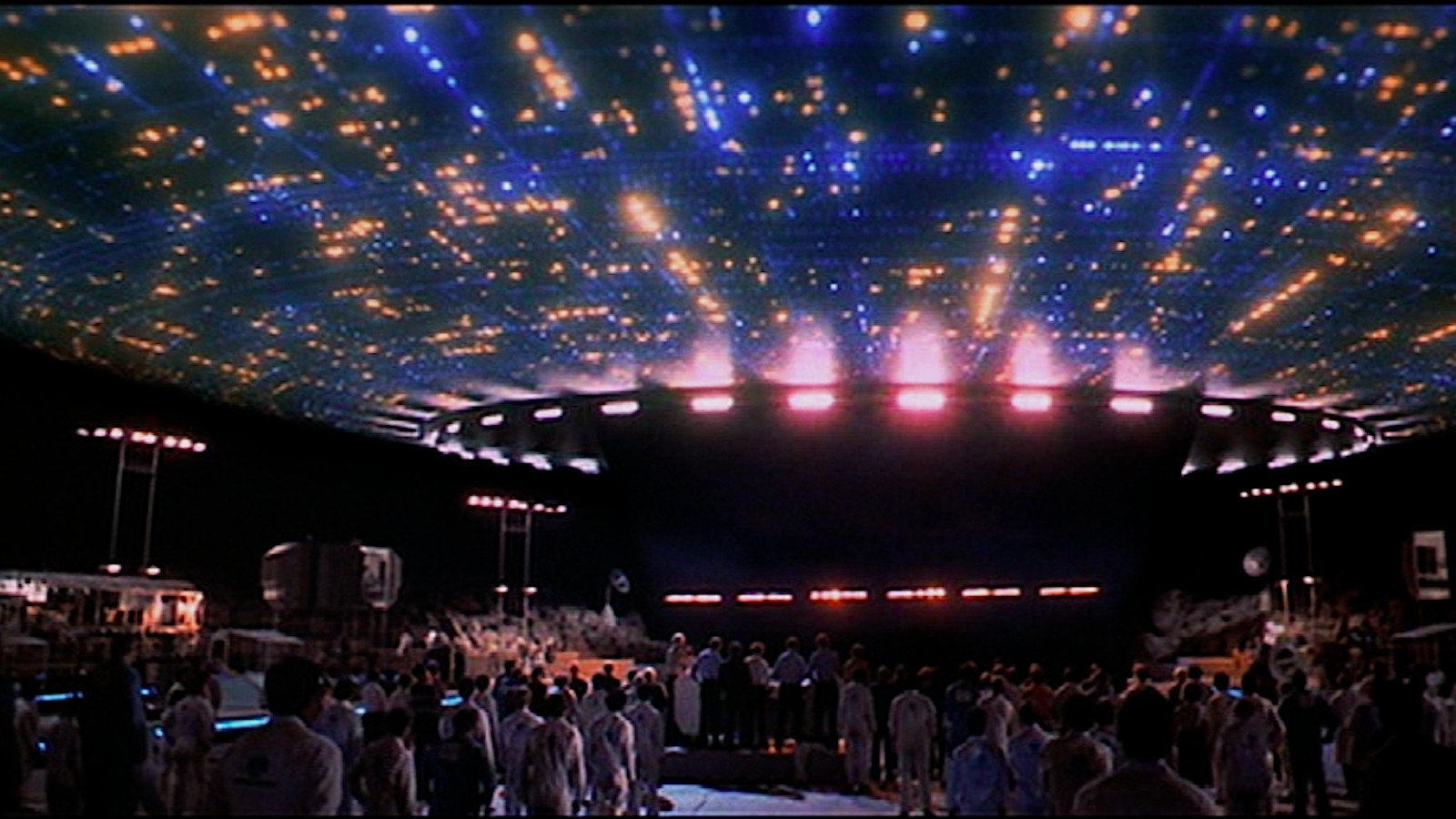

This week, our trip through the 70’s Spielberg canon continues with CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND. As captivating and filled with wonder as you remember, there’s also a bleak undertone to the film that may reveal more about its director and his then-place in the world than he even intended. Grab a plate of mashed potatoes and read along!

Welcome to Week Four of our first Annual Summer of Spielberg! This summer, we’re working our way through the 70’s canon of Steven Spielberg and we’ve reached yet another notable film in his then-young career that warrants much discussion.

It’s an early Spielberg epic exploring humanity’s response to seeing colored lights in the sky, where people and animals begin disappearing from a sleepy town in Southwestern America, and true UFO believers become obsessed with proving their creeds to their families and loved ones. It all ends, as you remember, with first contact officially being made, and the true intent of our alien visitors being revealed.

I speak, of course, of 1964’s FIRELIGHT.

It was technically Spielberg’s “first film”, a distinction that could just as easily be made about 1971’s DUEL and 1973’s THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS. He famously made it at the age of 17 on a budget of $500, and even more famously turned in his very first profit after screening the movie for one night in Phoenix, AZ and making $501 at the box office (Spielberg figured in an interview with James Lipton in INSIDE THE ACTORS’ STUDIO that they got 500 people in the theater, charged one dollar a head, and someone must have ended up paying two, hence the profit).

The vast majority of FIRELIGHT is unfortunately unavailable to the public; something like three minutes of its semi-unfathomable 135-minute run time remains. On the other hand, considering the cast was mostly theatre students from the local high school, as well as Steven’s sister Nancy, one has to imagine three minutes is more than enough to pull whatever you need out of what is ultimately a curiosity, the Steven Spielberg movie before there were Steven Spielberg movies.

Everyone seemingly moved on after FIRELIGHT’s one-night-only release date of March 24, 1964. But Spielberg clearly never shook the idea of aliens visiting our world, a story borne from a lifelong obsession with unidentified flying objects and watching a meteor shower with his father. The reason we know he never shook it is because FIRELIGHT more or less got remade as an actual Hollywood-backed film, CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND. Only this time, there was way more pressure on Spielberg, who in the thirteen years since FIRELIGHT had made a genuine paradigm-shifting blockbuster in JAWS and was now being looked at to deliver once again.

And…he did! Spielberg managed to match the lofty expectations generated from his water-bound blockbuster and made a film that is much bigger in scope that JAWS ever was. It’s also much more melancholy in ways I had forgotten about. Most importantly, it’s a movie that reflects more of its creator’s obsessions and state of mind than maybe was even intended at the time.

Let’s do it! It’s CLOSE ENCOUNTERS time.

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND (1977)

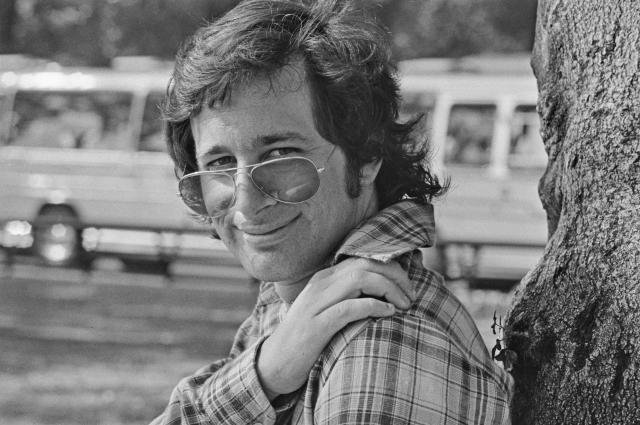

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Written by: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Richard Dreyfuss, Teri Garr, Melinda Dillon, Francois Truffaut

Released: November 16, 1977

Length: 135 minutes (theatrical version), 132 minutes (special edition), 137 minutes (director’s cut)

As one might imagine in a movie entitled CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, Spielberg’s fourth feature-length film, like many classic sci-fi stories before it, asks what might happen in a world where extraterrestrial beings finally reveal themselves to Earth. Its story consists of several threads that eventually weave together like a tapestry. There’s the tale of Roy Neary (Dreyfuss), who almost literally crosses paths with a UFO and becomes compelled to find it again. There’s Jillian Guiler (Dillon), whose little boy Barry is abducted by mysterious lights in the sky. There’s Claude Lacombe (Truffaut, the seminal French New Wave director making an extremely rare appearance in an English-speaking film), a representative of the French government who finds himself collaborating with the U.S. government on something incredible: establishing first contact. All parties will eventually find themselves in Wyoming, hoping to communicate with the aliens utilizing an established five tone sequence (you know the one, even if you think you don’t know it).

The most notable thing about taking CLOSE ENCOUNTERS sequentially is that, even though it’s not even close to being the first Spielberg movie, it may be the very first Genuine Spielberg Movie, one you’d be able to spot from a mile away. It has all the hallmarks one expects from his classics: we’ve got a fractured family (the Nearys), a lost child* (Barry), the wonders of space and the great beyond, benevolent alien beings, shadowy faceless government enemies and vehicles, and, most important of all, the Everyman selected by his circumstances to become the hero of an incredible story.

*Although, something I haven’t yet noted: essentially every one of Spielberg’s films prior to this have also included a missing child in some way. It’s more literal in THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS (the Poplins are trying to regain custody of baby Langston) and JAWS (the death of Alex Kintner), while in DUEL, the loss is more implied (David Mann’s family life is on the rocks). Steve’s been doing it from the beginning!

It’s all the more impressive that Spielberg was able to establish such a reliable template for himself when you consider how turbulent the movie’s creation really was. JAWS has taken up all the oxygen when it comes to “troubled 70’s Spielberg productions”, but CLOSE ENCOUNTERS did not itself have much of a smooth birth. Its initial conception goes back to 1973 as a film entitled WATCH THE SKIES, with Paul Schrader working on a first draft of the script. JAWS pushed everything back a year or so, and a major setback occurred when it turned out Spielberg fucking hated Schrader’s draft, eventually referring to it as “one of the most embarrassing screenplays ever professionally turned in to a major film studio or director”. Seems a bit harsh to me, but suffice to say, Spielberg and Schrader split over creative differences soon after. After several rounds of rewrites from folks like John Hill, David Giler and Matthew Robbins, Spielberg began taking a crack at the script himself, using the famous Disney song “When You Wish Upon a Star” as influence.

A couple of years later, once JAWS was in the rearview mirror and Spielberg’s alien project was finally ready to go, its producing studio, Columbia, ran head-on into financial issues. This already huge problem was exacerbated by the fact that CLOSE ENCOUNTERS’ budget grew exponentially. Spielberg had quoted the studio about $3 million in 1973; by the time its filming was completed, it sat at about $20 million. Lightning strikes and hurricanes destroyed much of the Alabama soundstages. A producer, Julia Phillips, eventually got fired for doing too much cocaine. Spielberg himself said the shooting experience for CLOSE ENCOUNTERS was “twice as bad” as JAWS, just to set the bar.

One of the seemingly biggest factors in the shoot being prolonged is the fact that Spielberg’s own vision for the film kept increasing in scope throughout the life of the movie, all the way up to and including its release. The production schedule kept lengthening as new ideas kept generating in Spielberg’s head, and he had issues defining the movie’s “wow-ness” in various cuts. Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond eventually had to drop out of reshoots due to other commitments (although a team including Douglas Slocombe took over, so perhaps everything worked out).

This all leads to one of the most famous aspects of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS: the existence of several cuts. The theatrical version was released in November of 1977, but Spielberg never seemed truly satisfied with the way it turned out. Despite having final cut privileges and a request to the studio for six more months, Spielberg agreed to have the movie released as it stood, only later leveraging its success to make a director’s cut in 1980. Famously, that director’s cut actually wound up being five minutes shorter, as he wound up going back and removing or shortening many other scenes (most notably the scene where Roy throws a bunch of bricks and dirt into the family kitchen), exercising an artist’s right to fuck with a completed work that his friend and colleague George Lucas would take to its absolute breaking point.

The Director’s Cut also features the addition of several minutes of footage, including an infamous, studio-mandated look at the insider of the mothership, a move that Spielberg regretted so much that it generated a third cut of the film, a VHS “Collector’s Edition” that included all the new and old footage, minus the mothership interior. There actually appears to be a fourth recut version floating out there, a syndicated television edition that was available on a 1990 Criterion Laserdisc.

(For what it’s worth, the version I watched was the theatrical version. It may be the only version I’ve seen. Maybe somewhere down the line, I’ll check out the other two versions just to say that I did. The Director’s Cut has its ardent supporters, up to and including the late Roger Ebert who called it better than the original. I just…man, Spielberg’s right, he shouldn’t have given in on the mothership interior. It seems so anti-imagination and, thus, anti-Spielberg. One of these days.)

The reason I bring all this extensive recut history up is that, whether he intended it or not, nothing could be more illustrative of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS’ main themes of single-minded obsession in the face of something extraordinary than this driving need for Spielberg to get the movie right. One can easily imagine him sifting through the footage of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS at various points of his life and looking much like Richard Dreyfuss hovering over those mashed potatoes. Hell, one can just as easily imagine him seeing that fateful meteor shower as a kid and getting that obsessive idea implanted in his head: “I have to tell this story.” He tries it once with FIRELIGHT, he tries it several times over several decades with CLOSE ENCOUNTERS, he comes back to it over and over in his filmography (picking it up next with E.T.). He keeps plugging away at that five-toned tune, hoping to finally make contact.

In that sense, you get more of Steven Spielberg’s psyche in Roy Neary than maybe he even meant to, which may be why subsequent editions tried to sand the edges off that particular storyline, even if said edges are just too jagged to ever be made smooth.

Oh yeah, that ending. I guess we should talk about that ending.

What really struck me about CLOSE ENCOUNTERS on this rewatch is just…how kind of sad the ending is, even a little bleak. Oh, sure, on the whole, the final half-hour or so is Spielberg firing on all cylinders. Humans and aliens slowly and successfully communicating via the usage of simple musical tones is pure Spielbergian fantasy (I mean this as a compliment). It’s thrilling and is perfectly paced, perfectly scored. It’s maybe the most parodied and memorable part of the whole film. Tonally and textually, the ending of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS is quite the crowd-pleaser.

No, I mean the way Roy Neary’s story actually concludes. Neary’s journey is, of course, the backbone of the entire picture. To recap, he is a lonely electrician who is merely in the right place at the right time to get an up-close encounter with a UFO. From then on, he becomes singular-minded and obsessive about an undefined shape. He sees it in his pillows, he draws it on his work notes, he famously builds it at the dinner table with his mashed potatoes.

The shape is revealed to be Devils Tower in Wyoming, the agreed landing spot of our alien visitors, the area where first contact will officially be made. Roy eventually begins to make his way over to Wyoming in order to fulfill his new destiny, but not before successfully scaring off his wife and kids. Prior to his departure to Wyoming, a morning of throwing bricks and dirt into the kitchen is enough to cause his wife Ronnie (Garr, in peak heartbreaking form) to take the kids to her sister’s for a while.

As I had correctly recalled, the movie ends with Roy being chosen by our alien visitors to come back with them into space, where he’ll be able to embark on the most incredible adventure any human could ever imagine being on. What I had forgotten, however, is that the scene of Ronnie leaving for her sister’s is the last time we see her or the kids in the movie ever again. There’s no resolution beat at the end where Ronnie realizes her husband was correct, no cut to them catching up with this incredible event over the broadcast news, no nothing. Frankly, positive resolution between Roy and Ronnie may not even be a realistic thing to hope for; I turned to my wife at the end of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS and asked her, “if I had all of a sudden starting acting like a lunatic, obsessed with a location and convinced aliens are speaking to me until you literally left the house, would it matter at all if I was later proven to be 100% correct in my beliefs?”, her immediate answer was “no”. It’s reasonable to believe Roy never sees Ronnie or his children ever again.

But then, such is the Great Theme of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS, that of single-minded devotion and obsession, bordering on religiosity. No matter what happened in their lives previous to the movie’s start, all of our principals have undergone a soul-rattling, magnificent experience. From the second the spaceship first arrives, the lives of Roy, Claude, and Jillian (and many nameless others) have diverged from their relatively normal paths. They are now responding to a higher calling, not unlike the many in history who have turned their backs on their loved ones and the lives they had built in order to better devote themselves to God, shaving their heads and vowing poverty and charity.

So, yeah, although it’s a wonderful and uplifting ending in terms of tone and texture, it’s difficult to call the conclusion of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS overall “happy”. The lives of those left behind have quite literally been ruined, or at least altered irrevocably. Subsequent editions have tried to trade out some of Roy’s crazier moments for scenes that play with more sympathy (like him breaking down inside his shower, for instance). But, it’s hard to edit or tinker around the fact that Roy ditches his life and loved ones to pursue a higher calling. It’s magical and devastating in equal measure.

In that sense, CLOSE ENCOUNTERS seems to be a story of emerging genius (and how closely it can be linked to genuine insanity), and I don’t think it’s an accident that this is the version of the UFO story that emerged once Spielberg took over the script himself. It’s also not surprising to me that Spielberg seemed to struggle with articulating it all, going back and tinkering with it two or three times. It’s sort of a movie about Spielberg at this time in his life, having changed Hollywood irrevocably and forging his path as an industry great while barely entering his thirties. Not that Spielberg broke the hearts of all of his loved ones in order to make fucking JAWS or anything, but there’s the feeling of truth to how Roy is drawn by a higher power to this jaw-dropping turn in his life.

That’s the power of lights in the sky. And meteor showers. And getting all your friends together to make a too-long movie that earns your first dollar. It just may trigger something in your brain and soul that kicks off a lifelong passion.

And the world may change along the way.

JAWS REDUX: SPIELBERG SUMMER Continues!

This week, the First Annual Spielberg Summer begins with almost certainly his biggest movie of the 70’s, JAWS! It’s a movie we all know well and have likely discussed in granular depth over and over (I’ve even written about it in this space before!). But it turns out, when you see JAWS in a packed movie theatre, like I did earlier this month, it feels like a brand new film all over again. The magic of the movies!

Hello, friends! Our little stroll through the Steven Spielberg films of the 1970’s resumes this week as The First Annual Spielberg Summer continues.

Today, we’ve reached the first truly bigger-than-life, overwhelming movie in his oeuvre. JAWS is on the short list of most important movies ever made, even if you’re only measuring individual impact on the trajectory of Hollywood and filmmaking (and to be clear, JAWS stands on its own fins even when stripped of that context). If you’re part of a certain generation of film fan, it’s almost certainly one of the movies that got you into movies in the first place.

It’s possible some of you have been waiting for this article since Spielberg Summer began. Perhaps you’ve been looking forward to a brief history of the famously-snakebitten production, and how Spielberg managed to turn chicken shit into chicken salad by allowing significant mechanical failures (say it with with me now, “they couldn’t get the shark to work”) to actually enhance the film’s drama, conflicts and terror, cloaking the titular beast in the shadows of the audience’s mind and imagination. You likely are anxious to celebrate JAWS’ second-to-none cast, especially the main trio of Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw. It’d be wise to talk about how fully developed Sgt. Brody really is, and how his fear of the water and his drive for integrity are constantly thrown into conflict by a never-ending set of exterior circumstances. Hell, a good discussion could be had about how beautifully the largely land based first half informs the waterlogged second half, by establishing stakes and psychologies before sending everybody out to sea.

It’d be a good article to write this week.

Except, well….I’ve written it already.

Yeah, I’ve previously talked about JAWS, and it wasn’t even that long ago. About two years ago, in this very (differently branded) space, I did a summer series on the entire JAWS franchise, including the famous 3D sequel, as well as the not-so-famous Italian knock-off sequel CRUEL JAWS. I can’t speak to the actual quality of that article, although I was two years less good than I am now, so you can run your own math and make that determination for yourself. My point is, what was created in 2022 is more or less the same article I would have written now.

It’s a mildly interesting conundrum I find myself in; this is the first time I’m writing a second article about a movie. Obviously, I knew this was going to be a problem going into this first round of Spielberg retrospectives, and I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about what fresh angle to take. I tried to resist the idea of just rerunning that one under the Crittical Analysis brand, as that comes with an implied level of laziness there that I wasn’t ready to reconcile within myself. But, I’ll be honest, I wasn’t coming up with a better alternative; after all, JAWS is a difficult movie to find new unique angles about fifty years later.

But, then…the Monday before the Fourth of July, I had the opportunity to see JAWS in an actual, genuine movie theater for maybe the first time ever.

And it was like seeing it for the first time.

“Oh, new angle.”

This week’s article might be a little briefer than others in this series, and certainly a little different. But my last experience with JAWS was a genuinely different one, and I would remiss if I didn’t take the opportunity to document it.

So here it is. JAWS!

JAWS (1975)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Written by: Peter Benchley, Carl Gottlieb

Starring: Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss, Robert Shaw, Lorraine Gary, Murray Hamilton

Released: June 20, 1975

Length: 124 minutes

The ability to watch a classic film on the big screen is one of life’s amazing little treats. It can often feel like the difference between seeing the Mona Lisa actually hanging in the Louvre and looking at a photo of it on your phone. You get the idea either way, but actually being in Paris, seeing it at its actual intended size, surrounded by other human beings, all there to do the same thing…it’s just a whole different experience.

Unfortunately, the ability to actually see classic films in a theater often depends on where you live. If you live in a major city, or at least within the proximity of one, you’re usually in good shape. You will likely have the ability to throw a dart randomly at the newspaper movie listings* and land on the opportunity to see one of the greatest movies ever made, usually well within driving distance.

*I know that there are no such things as “movie listings” or “newspapers'' anymore, but I don’t think the dart metaphor works as well with a laptop or phone screen. Don’t want anybody cracking their screens, ya know? You’ll just have to indulge me on this one.

If you live in a mid-to-small market like I do, however, you’re usually at the mercy of the small handful of revival houses that you have. I can only speak for myself, but in Sacramento, CA, there are three places in town and one of them (The Dreamland Cinema) is teeny-tiny. That leaves The Tower and The Crest for your revivals and that is literally it. Oh, sure, we have lots of regular movie theaters, but most of the chain mega-plexes in town have stopped doing Flashback Features long ago. So it’s just these three locations holding down the fort right now. At least two of them feel under constant threat of closure.

Luckily, I live down the street from one of them (the Tower), and they seem to be relatively awake at the wheel. Not only is there a consistent stream of repertory screenings throughout the year, they appear to be paying attention to the time of year in which they’re screening. It’s how people in town can see a whole festival of Hitchcock movies in October. It’s how my wife and I got to see WHEN HARRY MET SALLY… on New Year’s Eve last year. It’s also what allowed us to see JAWS on a big screen the week of July 4th.

We had seen other classic screenings at this theater before, and we had never been in danger of being the only people there or anything, but it truly shocked me at just how many people showed up to JAWS that night. It probably shouldn’t have been a surprise; after all, we’re talking about one of the most famous and popular movies ever made even to this day, the movie that more or less invented the “summer blockbuster”*. But, really, I had never seen the Tower lobby that full before that night. Again, this was a Monday night. That was the first sign that we were potentially in for a special night.

*Yes, this means you can technically draw a straight line between JAWS and DEADPOOL & WOLVERINE. Whether this is a mark for it or a knock against it, I’ll leave for you to determine.

The second sign that magic was in the air came relatively early on, when the entire town of Amity gathers in the police station following the gruesome death of little Alex Kintner, crowding around Sheriff Brody (Scheider) and Mayor Larry Vaughn (Hamilton), demanding an explanation and plan of action from their leadership. As Brody struggles to wrangle the masses, the nasty sound of fingernails scratching across a chalkboard cuts through the din. Everyone turns around to see the grizzled shark hunter Quint (Shaw).

The scene becomes dead silent.

In the movie theater, however, the room filled with the sound of something like four beers all cracking open at once.

The crowd was locked in. Summer had begun.

It really is something to watch a classic crowd-pleaser work its magic and…well…please the crowd! What follows is a list of just ten of the endless amounts of JAWS moments that absolutely crushed that night:

Brody telling a fellow beach-goer “That’s some bad hat, Harry.”

The guy who exclaims “A whaaaaat?”

The corpse popping out of the busted hull of that sunken ship (no, seriously, this one killed. Screams in the audience and everything).

Brody filling his glass near the brim with red wine.

“Michael, did you hear your father? Get out of the water now!”

Quint crushing his beer can with one hand, followed by Hooper weakly crushing his styrofoam cup.

Hooper screaming “aye aye” to Quint in that intensely sarcastic pirate voice.

The USS Indianapolis speech (the room was dead silent, no beer cracking this time).

Pretty much every Quint rendition of “Farewell and Adieu”.

It all reminded me of two things: one, I reflected back on the Big Important Issue in the far-away year of 2019, where Martin Scorsese declared Marvel movies as not cinema, but theme parks. As you may remember, this triggered responses from James Gunn and Joss Whedon (back when Whedon felt compelled to make a statement about anything at all). It also drew ire from superhero fans all across the Internet; it still appears to be a sore spot for some to this day.

And, look, I’m not here to re-litigate a wound. Although I do find the reaction overblown relative to what is ultimately just a qualified opinion (as far as I know, Scorsese didn’t say “and you’re all dipshits for watching them”, he just said they weren’t cinema to him), I get that it can be annoying to devote your free time to something that gets dismissed so broadly by somebody with authority. That said, speaking as someone who has found enjoyment in both the MCU and Scorsese films, the reason I never got worked up about Marty’s comments is because “theme park attraction” is neither an inaccurate description of what modern superhero movies ultimately are, nor does it need to be a pejorative term in and of itself, so long as the movie in question is a well-built and thoughtfully constructed roller coaster.

What are theme park rides, after all? They are mechanisms for us to take a break from our lives, even if just for a little bit, in order to put ourselves in some artificial danger and generate some thrills and emotions together, even if we’re all walking in as strangers. It’s something for us to enjoy together as people. The best ones work even if you’ve ridden it over and over. At their finest, movies are roller-coasters.

JAWS is a pitch-perfect example of that. On July 1st, 2024, a bunch of people filed into the main room of the Tower Theatre with just one commonality (“I wanna watch JAWS tonight!”), paying to see a movie we all probably already owned at home and had almost certainly all seen multiple times since childhood. And, you know what? The roller coaster was just as fucking good today as it was when we all first rode it decades ago. In truth, it hits all the more when you have a forged, temporary community to ride it with.

(Of course, JAWS isn’t just mindless thrills and chills, it’s also well-built in terms of setting up its characters and stakes, which makes us as an audience care, which makes the moments of action and terror hit all the more because we’re bought in, but now I’m getting into first article territory here. I just bring it up because this is the element that some of the MCU movies lack, especially some of the latter-day ones, after characters got firmly established and the ability to coast on good vibes became available. Again, just in my opinion as a fan. Anyway.)

That brings me to my second thing: it’s more fun to see a movie in theaters. It just is. And there so many things currently working against the in-person experience right now. For one, watching movies at home has never become more technically convenient; even the ability to afford one or two streaming services gives you access to a never-ending array of movies of all types, age, and quality. For two, movie tickets have obviously skyrocketed in price, just in time for inflation to grow out of control and wages to seemingly stagnate across the board, making a trip to the movies an easy luxury to cut in tough times (especially if you have a child or two).

For three (and, I think, final…I know I’m currently in a numbered list within a numbered list, I promise I’m going somewhere), the in-person experience just may not be available depending on where you live. Going back to the beginning of this article that is technically about JAWS, especially when it comes to classic cinema, you may just be completely fucked if there’s no house in town that screens them. This can be especially brutal considering, if you run in any sort of cinephile circles for more than ten minutes, you’ll run into the common piece of wisdom that “if you didn’t see [insert movie], you didn’t see it right”. It’s a frustrating thing to come across when your options are to watch a movie on the Criterion Channel at home, or not see it at all.

My point being…if you have the opportunity to see a beloved movie from any decade, and it even slightly works for you in terms of time, distance, and finance…grab it with all ten fingers and just do it. You’ll be very unlikely to regret it. JAWS on July 1st, 2024 was a good illustration as to why. Here is a movie playing out in front of me, one that I had seen probably a dozen times in my thirty-six years on Earth, and it was like a brand new adventure. People were screaming. Hooting and hollering. Cracking open their beers when something cool as fuck was happening.

There was nothing like it. It was clear as day at that moment why JAWS and Steven Spielberg helped change Hollywood filmmaking forever.

I can’t wait to do it again. After all, the damn thing is turning fifty next year.

But until then….farewell and adieu.

On the Road with THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS: Spielberg Summer Continues!

Spielberg Summer continues with THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS, another road movie from the up-and-coming director. However, with an increase in scope and a set of terrific performances, Steven Spielberg’s first venture onto the silver screen becomes a slept-on gem.

Hello! All summer, I’ll be working my way through the five films Steven Spielberg directed in the 1970’s. Two weeks ago, we kicked things off with DUEL, and things continue forth this week! If you like what you read, stick around! More to come…..

As mentioned in the first installment of Spielberg Summer two weeks ago, one of the aspects of working through Steven Spielberg’s filmography I was most looking forward to was knocking out the not-insubstantial amount of his movies I hadn’t managed to watch already, especially the blank spaces from the twentieth century. Yeah, obviously, I’m eager to revisit stone-cold classics like JAWS and CLOSE ENCOUNTERS, but each decade of his career contains at least one movie I just straight up haven’t seen, like little Christmas presents waiting to be opened.

Well, here we are, Week 2 of the First Annual Spielberg Summer and I’ve already reached my first first-time watch!

Up until about two weeks ago, I knew THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS primarily as that movie one sees in the form of clips near the beginning of any given Spielberg documentary or retrospective. Operating under fifty years worth of hindsight, SUGARLAND EXPRESS feels like a movie hidden between Spielberg’s television career culmination in DUEL and his stratospheric jump into popular culture in JAWS. It’s a film not talked about much in 2024 outside of the context of “Steven Spielberg’s first theatrical film”. All I really knew about its story (again, just off of very brief clips) was that Goldie Hawn was in a car and she’s looking for…a baby, I think? I presumed it was her baby? I never ventured forth to find out. There were just always bigger Spielberg movies to jump into or revisit, and the opportunity to knock this one off the watchlist never arrived.

It’s my pleasure, then, to report that it was a delight watching THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS with a clear heart and fresh mind (aka, what if I didn’t know this was directed by the man soon to become the most famous and powerful director of my lifetime?). It turns out I was right about Goldie Hawn being in a car, and she’s absolutely looking for her baby, so I was off to a good start immediately. What I hadn’t gleaned was that THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS is a scrappy, sad, spookily prescient movie about America’s unique intersecting relationship with desperation, crime, and media, featuring a trio of lively and shifting performances from Goldie Hawn, William Atherton, and Michael Sacks. What’s not to like about it? Seriously, what?

THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS (1974)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Written by: Hal Barwood, Matthew Robbins

Starring: Goldie Hawn, William Atherton, Ben Johnson, Michael Sacks

Released: March 31, 1974

Length: 110 minutes

THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS tells the fairly straightforward story of the recently released Lou Jean Poplin (Goldie Hawn) and the still-incarcerated Clovis Poplin (William Atherton). One fateful day in Texas, Lou Jean visits Clovis at his minimum-security prison with a mission: their young son is being put into foster care in the town of Sugar Land, and she’s determined to get him back. Following a relatively efficient break-out, almost nothing about this plan works out in any way. After the elderly couple they’ve convinced to give them a ride get pulled over by Patrolman Maxwell Slide (Michael Sacks), the Poplins are forced to commandeer the patrolman’s vehicle, as well as the patrolman himself. As the three improvise their way towards Sugar Land, it’s up to Captain Harlin Tanner (Ben Johnson) to figure out how to guide this situation to a non-tragic conclusion, even as the Poplins’ increasing media profile (as well as the fact that - and this cannot be emphasized enough - they have no idea what the fuck they’re doing) and notoriety may prove that an impossible mission.

The first thing that leaps out about THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS after watching DUEL is that…hey, it’s essentially another car chase movie! The scope has definitely increased exponentially; instead of one lone visible character, we have somewhere around ten speaking roles. Instead of two vehicles, there are seemingly hundreds of cars getting demolished by the film’s end. But, at its core, it’s another Spielberg movie exploring characters trapped in their cars trying to get from Point A to Point B in desolate America. One wonders if those who had caught both movies at the time just viewed Spielberg as “that car chase guy” (as opposed to the smart person I would have been at the time; I likely would have walked out of the theater in 1974 and said something like, “I bet the fella that made that movie is going to do a shark movie that’s going to alter Hollywood forever, just you watch!”).

The second thing that leaps out about THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS is how many other pieces of popular culture are conjured in the mind as its story unfolds. In particular, the growing media scrum surrounding Lou Jean and Clovis lightly evokes Billy Wilder’s deeply cynical ACE IN THE HOLE (although Spielberg never gets anywhere as bitter or acidic as that particular Kirk Douglas masterpiece). Of course, one cannot watch a pair of criminals running towards a tragic end without thinking of BONNIE AND CLYDE. However, when you watch enough moments of people cheering Lou Jean on, imploring the young couple to not give up, of crowds gathering around the car with signs of encouragement…you can’t help but think about O.J. Simpson when watching SUGARLAND EXPRESS in the here and now.

It’s worth mentioning at this point that the tale of Lou Jean and Clovis is based on the real story of Ila Fae Holiday and Robert Dent, although like all factual accounts in film, SUGARLAND EXPRESS understandably plays somewhat fast and loose with the details (Bobby never broke out of prison, for instance). What does appear to be true, though, is the fact that they led a very slow-moving police chase through Texas, one that eventually caught the eye of local TV crews and bystanders. For a brief moment, Holiday and Dent held court against the state, and everyone just…watched and rooted them on. The O.J. story became a circus for a million reasons that are way above the weight of the Holiday/Dent story, but little forgotten sensations like theirs (and THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS) prove that, even if O.J. wasn’t a beloved athlete and pitchman,even if the country hadn’t been in the middle of yet another of its famous “racial reckonings”, even if the whole thing didn’t go down in Los Angeles (the epicenter of front-facing American scandals), people might have been sucked in anyway. Folks love a good story, and they especially love an underdog Besides, who can’t relate to a mother trying to reunite with their child? Screenwriters Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins understood this even at the time, and their screenplay reflects that deep knowledge.

THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS is one of those movies full of interesting faces embodying interesting characters. Consider the moment where the gas station guy whose store gets commandeered by the police and is implored to take it up with the captain, leading to him wandering in the background from car to car asking who the captain is. It’s ultimately throw-away, only there to add to the chaos that surrounds the Poplins from the jump. But it’s a moment so filled with life and relatability (how the fuck would he know who the captain is, anyway?) The whole movie is like this; everyone is anchored in Spielberg-world as someone with feelings and perspective; even a character that could have been easily made a villain (the foster mom) ultimately ends up being sympathetic, capable of love, and worthy of protection.

However, THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS lives and dies on the four performances at its center. That brings me to the third thing that stood out to me about it: why didn’t any of you tell me William Atherton was in, like, every frame of this? A long time menace in the minds of people my age and ten years younger/older as the dickless EPA agent in GHOSTBUSTERS, it was stunning to see him ten years younger and so human and sympathetic. What struck me the most about Clovis is his dichotomy; he is alternately just as motivated to reunite with his child as he is terrified about the escalation of possible consequences if they move forward with their highly-improvised plan.

When I reflect on Atherton as Clovis, I think about maybe my favorite scene in the whole movie: Clovis and Lou Jean have holed up in a used car lot and begin watching a Wile E. Coyote cartoon playing at the drive-in theater across the street. Although they have no sound, Clovis provides all of the wacky sound effects for Lou Jean. As the cartoon continues, Wile E. makes one of his classic errors* and careens off a cliff. As the woeful cartoon coyote makes contact with the canyon, Clovis stops making noises and just kind of takes it all in. He seems to be relating to Wile E.’s plight and fate at that moment; the Poplins seem fated to crash and burn off the side of a cliff themselves.

*Undoubtedly off the back of trusting his hard earned cash with the ACME Corporation once again, but never mind.

Ben Johnson and Michael Sacks are also quite effective in their respective roles as pseudo father figure and unexpected ally. But it’s Goldie Hawn that was the biggest revelation at the time of release. I’m not a Goldie scholar, although I’m aware that her early shtick was that of a dizzy blonde on projects like Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In and the film CACTUS FLOWER, which won her an early Best Supporting Actress Academy Award in 1969. Her Lou Jean feels somewhat like a riff off that persona; Lou Jean is definitely excitable and highly naive, and one could argue her lack of any plan characterizes her as ditzy. But there’s a real pain and emotion behind all the outer chaos that makes her quite compelling, and makes the SUGARLAND EXPRESS finale hurt all the more. I thought a lot about a similar trick Paul Thomas Anderson pulled with Adam Sandler’s famous manboy act in PUNCH DRUNK LOVE. In both cases, an inner humanity is found through a comedic persona. To my knowledge, Hawn and Spielberg never worked again, and it’s a shame.

THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS also begins Spielberg’s ability to collaborate with major Hollywood talent, even at the unfathomable age of 27 (!). The cinematographer for SUGARLAND EXPRESS was none other than Vilmos Zsigmond, one of the biggest keys to the way the New Hollywood movement looked. The amount of major directors he shot movies for is staggering: besides future collaborations with Spielberg, he also worked with Brian De Palma, Robert Altman, Peter Fonda, George Miller, Jack Nicholson, Sean Penn, Richard Donner, Woody Allen, Roland Joffe, Martha Coolidge and, of course, Kevin Smith. With SUGARLAND EXPRESS, you couldn’t ask for a movie that has the texture and feel of a great 70’s American movie more; it’s equal parts dusty, melancholy, and bittersweet.

Zsigmond actually ended up being a key mentor to Spielberg, and was able to filter the young up-and-comer’s unique emotional style through good old-fashioned functionality. In particular, Zsigmond would refuse to start shooting a particular shot until Spielberg could articulate from whose point of view it was meant to express (i.e. justifying the shot by saying “it looked pretty and interesting” wasn’t going to be acceptable). To Spielberg’s credit, he accepted the on-the-fly mentorship. In short, even if THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS is a more minor film in the Spielberg canon, the things he learned throughout its creation would be indispensable in his approaches toward his own future masterpieces.

Then, of course, there’s that score. Yes, perhaps the most consequential thing about THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS is that it’s the first collaboration between Spielberg and John Williams. By 1974, Williams was already a well-accomplished film composer in the 50’s and 60’s, having worked on projects as diverse as a handful of GIDGET flicks, William Wyler’s HOW TO STEAL A MILLION, the Peter O’Toole musical GOODBYE, MR. CHIPS and the infamous camp classic THE VALLEY OF THE DOLLS. By 1971, he had already secured an Academy Award for Best Scoring off his work with FIDDLER ON THE ROOF. However, his initial collaboration with Spielberg here would prove to be the start of a path that led to his Hollywood canonization.

(As far as Williams’ specific score for SUGARLAND EXPRESS, it’s solid, although I couldn’t help but notice that the main harmonica theme sounds like somebody was trying to sneak in the melody to The Twelve Days of Christmas before chickening out at the last second. Listen to it and decide for yourself, just as long as you understand that you’re going to think I’m right.)

Funnily enough, THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS stands as the only movie Spielberg ever submitted for Palme d’or consideration, a ballsy move that I’m forced to extend my respect towards. Alas, didn’t win (the 1974 Palme d’or went to THE CONVERSATION instead; whatareyagonna do?), although he, Barwood and Robbins walked away with a Best Screenplay award at that year’s Cannes festival. That would do it as far as major awards. As far as critical reception, reviews seemed mixed. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert were individually low on it, while Pauline Kael was quite taken.

As far as the general public, there weren’t a ton of people that showed up for it. THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS only made about $12 million worldwide, which was anemic enough for Universal to call off the game and pull the film from theaters after only two weeks. This seems unfair considering the movie was made for $3 million, but then I guess this is why I don’t make the big bucks. One would imagine, in any other world, Spielberg’s goose might have been a bit cooked here.

Thankfully for the rest of us, we live in this world, one in which Spielberg’s next project for Universal was already underway and, in fact, had begun before THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS had even been released. That project is a little beach movie called…..well, we’ll talk about it in two weeks.

(I like to imagine there’s a hypothetical reader out there who voraciously read an essay on THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS from start to finish but has managed to never hear of JAWS in any way, shape or form. If you’re that reader, uh….spoilers, I guess.)

Driving Around With DUEL: SPIELBERG SUMMER Begins!

This week, we begin our dive into the 70’s filmography of Steven Spielberg by taking a look at one of the finest television movies of them all, DUEL. The thing everyone remembers is that truck, but what makes the flick sing is the relatable sad sack driving the other car. Welcome to SPIELBERG SUMMER!

From the time I started writing about movies as a hobby, a thought had been rattling around in my brain.

How am I going to do it?

It’s one of the first things that crossed my mind after working my way through the filmography of Martin Scorsese during 2020, a project from an earlier iteration of this blog finally completed. As I got to thinking of other legendary directors with a varied and rich body of work, I had to ignore the voice in my head that kept repeating a simple phrase.

You should do it.

I had brought up the idea to friends in the past, and they would say the same thing I had been telling myself for four years.

Do it.

Just do it.

So, fine. I’m doing it.

Just like I’m guessing pretty much every film fan born between 1970 and 1990, Steven Spielberg was the first director whose work I fell in love with. I have my mom to credit for that one; she made damn sure I was going to be growing up seeing stuff like JAWS, RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, and JURASSIC PARK. I get the instinct; all three of those movies were and remain stone cold classics, the type of movies you’ve literally never heard anyone say a bad word about. But, in truth, I think my mom has always pulled inspiration from Spielberg’s personal story: born into a family directly affected by the Holocaust, Steven had to rise above both antisemetic attacks in school and struggles with his faith by burying himself into his obsessions with watching and making movies. I never suffered anything even remotely close to that in my own life, but considering I was a kid who sometimes felt aimless and anxious even at the age of nine, I think my mom found some sort of path forward with sharing Spielberg’s biography and career with me. (Does this make me the Steven Spielberg of writing intermittently about movies? Who’s to say?)

So okay, fine, I’m doing it. But it didn’t solve the bigger issue….how do I do it? As of this writing, Spielberg has made a grand total of 36 feature length films* which, by my math, is sixteen weeks shy of 52. To tackle Spielberg’s filmography the way it deserves to be tackled (individually, week by week) would essentially make this a year-long project. And that presumes I don’t get distracted by a shiny object somewhere along the way, and lord knows I have too much ADHD flowing through my veins for that.

*Yes, for the purpose of actually being able to get through this without running the risk of passing away before its completion, I’m skipping his episodic television work, as well as his producing credits, although I could likely do a whole year on just TINY TOON ADVENTURES, ANIMANIACS and FREAKAZOID alone.

But then, I realized….why not take it decade by decade? After all, the last half century has yielded specific ups and downs in Spielberg’s career, and each individual decade has at least one masterpiece that will be a treat to revisit, as well as some less popular works I’ve never seen. Why don’t we just slow roll this thing and dedicate the next few summers in this space to going through every Steven Spielberg movie ever made? What are you going to do, fight me on it?

So…let’s do this! I’m finally doing it. I’m finally working my way through the works of Steven Spielberg. Starting today, and every other week for the next ten weeks, we’re going to explore the five feature-length movies he made between 1971 and 1979! For reference, we would begin with today’s subject, DUEL. Following that will be THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS, JAWS, CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND and, of course, 1941. Good times.

Even if we weren’t going chronologically, the seventies would make for an excellent and intriguing starting point for a Spielberg career retrospective. It’s easy to forget, now that the Steven Spielberg Brand has been so well-established, but he was an important thread in the New Hollywood movement. Of course, he was arguably an equally important thread in putting an end to what New Hollywood typically stood for. By cutting his teeth on more character driven (and moderately budgeted) work such as SUGARLAND EXPRESS, Spielberg ushered in a new era of busting blocks and popping corn with JAWS and CLOSE ENCOUNTERS. By the end of the 70’s, Hollywood had seemed to form into something more populist. As a result, it sometimes feels like Spielberg’s artistic integrity has been mildly questioned, as least in comparison to other seventies titans like Martin Scorsese, Terrence Malick, John Cassavetes and Stanley Kubrick.

But, I would argue the reason “Spielberg” became a genre all its own is because he never lost that knack for character-driven drama, even amidst the spectacle of his most famous works. Yeah, you show up to JAWS for the scary shark, but it’s the beautifully understated performance of Roy Scheider that stays with you. It’s the persistent quest of Roy Neary that makes CLOSE ENCOUNTERS what it is. It’s even, as you’ll see, the relatable loserdom of David Mann that makes DUEL so potent. Although it’ll be interesting to track the quality of his output as we get closer to modern day, it seems to be that he rarely loses at least that key quality.

Taking his seventies’ work as a single set is to watch him navigate his inherent skills behind the camera, and his natural interests as a human, and filter them through an increasing scope before it arguably grows too unwieldy and blows up on him. Needless to say, I’m excited. I hope you are as well.

Welcome to SPIELBERG SUMMER: YEAR ONE - THE SEVENTIES!

DUEL (1971)

Starring: Dennis Weaver

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Written by: Richard Matheson

Length: 74 minutes (expanded to 90 minutes for 1983 theatrical run)

Released: November 13, 1971

I can’t say with any confidence how many people reading this have ever truly tried to commute within the confines of California. What I can say, though, is that I spent four years of my life driving the 53 miles between Sacramento and Stockton twice a day, five days a week. I don’t know that the entire 110,240 miles really looked like the stretch of road that serves as the setting for DUEL, but I promise that every miserable inch of that commute 100% felt like it.

Even if you’ve never seen DUEL, you’ve almost certainly heard of it, even if just as “Steven Spielberg’s first film!!” You likely know it vaguely as “that movie where a guy gets chased around by a truck”. If your awareness only runs that deep, then, you’ll be surprised to hear that DUEL is...a movie where…a guy gets chased around…

…by a truck.

It turns out that DUEL is a masterpiece in high-level summary. It’s a TV movie made with all A-plot in mind; David Mann (Dennis Weaver) is a salesman who has hit the road in order to meet with a client. His loping, winding, boring drive from Point A to Point B is interrupted when a truck allows him to pass through the one-lane highway they’re both on, only to immediately begin to try to run David off the road. The aggressive driver is never seen, turning the truck itself into a character, one that billows enough smoke to connote the devil himself. Along the way, David makes several pit stops, including a diner, a phone booth on the property of an exotic animal trainer, and an abandoned school bus. By the end, either David or the truck driver will find themselves in a fiery inferno. Who will it be? Man or machine?

(You should know, by the way, that I resisted making that last sentence “Mann or machine?”, but only because I saw somebody else make that joke already. Anyway.)

I remember seeing DUEL for the first time about twenty years ago when Universal first released it on DVD back in 2004. Up to that point, I had known DUEL exclusively as that aforementioned mythical “first Spielberg movie”, the one that launched the wunderkind TV director’s career, the best TV movie of all time, the cult classic to end all cult classics. To be honest, though, I don’t have much of a memory of that first watch. It’s entirely possible I didn’t even finish it. For better or worse, I found it to be the exact movie I was sold. A guy is driving down the road and starts getting increasingly harassed by another guy in a truck. Extend and escalate for 90 minutes, bada bing, bada boom, you’ve got DUEL. As a (extremely relative) longtime Spielberg fan, I was glad I saw it. But it was mostly a curiosity and nothing further.

DUEL, then, gains a ton of power as one marches into adulthood and you begin to realize how much of your life is spent sitting in a car, zoning out and winding through some unremarkable road or highway. There are days when you reflect on your commute and wonder how you even managed to get home at all, for as little brain power as you were putting into it all. Drive long enough, turn your brain down enough, and it’s entirely possible you could find yourself in a life-or-death struggle between you and some asshole in a truck.

As it turns out, the genius of the November 13th, 1971 ABC Movie of the Week is that the horror is plausible. It could even happen to you later today.

Needless to say, I found DUEL wildly compelling this time around.

———

By 1971, Steven Spielberg was already a director on the way up; after making his debut by directing Joan Crawford in the 1969 pilot of Rod Serling’s Night Gallery, Spielberg became a TV director for hire, working on famous programs such as Columbo and Marcus Welby, M.D., learning old-school techniques on the way, while also finding room to experiment where he could. Eventually, his reputation was steady enough that Universal commissioned him to do four television movies, a deal that ended up yielding only three. The second was 1972’s SOMETHING EVIL (CBS), the third was 1973’s SAVAGE (NBC). The first, and easily most famous, was 1971’s DUEL (ABC).

It should be noted that the version of DUEL that aired in 1971 was a lean, mean 71-minute cut of the film, perfect for the 90-minute time slot it had been afforded. The version of DUEL I suspect most people have seen is the 90-minute cut that was created for a 1983 theatrical run, a project commissioned off the back of Spielberg’s remarkable run in 1982 (his directing of E.T. and his co-writing and producing of POLTERGEIST). Some of the extra scenes feel fairly obvious and perfunctory (I’ll talk about one of them in a second); some scenes surprisingly fit right in, the primary of which being a sequence with the broken down school bus. People seem a little split on this part, with some characterizing it as too Disney-esque. I actually kind of dug it, as it’s a moment where the unseen truck driver varies up their method of torture, shifting from aggression to something more beneath-the-surface sinister. In this sequence, David is hesitant to help push the stranded school bus, not only because he’s in fear of his life, but because he’s not particularly thrilled about his hood getting scratched up. When the truck reappears to continue chasing David, it takes a quick time out to pleasantly push the bus back onto the road. For lack of a better phrase, David’s cucking is complete.

That’s another aspect of DUEL, by the way, that you just don’t get as a kid: how the main tormentor for David Mann isn’t the mysterious aggressor in the truck, it’s life itself.

The obvious question regarding extending out the premise of DUEL more than a few scenes, let alone to ninety minutes, is “why doesn’t David just let this go?” Yes, obviously, both he and the truck driver eventually reach a point of no return, where both pairs of heels have been dug in too far for this not to end in someone’s death. However, the genius of the storytelling here is how deftly, but emphatically, it shows us just how powerless David really is in his day-to-day life. His commute is constant and extremely boring. His job is vaguely defined, but involves him selling something nondescript to various faceless clients. It’s implied that his private life provides no relief, as he quips to a gas station attendant who just referred to him as boss, “not at home, I’m not”.

(It should be mentioned that the ninety minute cut makes a bigger deal of the home life thing, with an entire added sequence of David on a pay phone having a tense, emasculating conversation with his wife. We get to see the wife and everything. It’s filmed with competence and well framed, and if you’re trying to add 18 minutes to a movie, it’s a logical place to expand. But…I don’t really like it. The scene is proof positive that one need not visualize what can be expressed in a single sentence. Sorry, I just wanted to vent about it. Moving on.)

David is just kind of a loser, or at least (more importantly) he perceives himself as one. So when a truck loping along the same stretch of road as him starts being kind of a dick, he decides to stand his ground for once and be a dick right back. And, as it goes for most of us, this proves to be his folly. It’s maybe the ultimate inciting incident for a story, one that makes you yell at the screen for a character to just drop it, while knowing deep down that you may have done something similar yourself. It’s an understandable and recognizable human instinct and that’s why it’s so compelling. It helps that Dennis Weaver plays David with such an Everyman quality; even when he’s panicking and making poor decisions, you can’t help but recognize parts of yourself within him.

There are issues with the script, a Richard Matheson adaptation of his own short story, the primary of which being the overwritten voiceover monologues for Weaver. It’s got to be terrifying to write a script with almost no dialogue, and I’m sure it felt like there was a need to verbalize something about this crazy situation David finds himself in. But the voiceovers are almost uniformly unnecessary, to the point where I was convinced these were additional theatrical cut extensions, meant to streamline the emotions of the picture. Alas, no, they were there from the jump, an unusual misstep for an otherwise tight film.

One has to figure, though, that these voiceovers stand out all the more because there’s so much else right about DUEL. The constant creativity; its sense of rapid, but never overwhelming, pace; its Hitchcock-ian sense of tension building (the best moment of the movie might be David trying, and failing, to track the type of boots his assailant wears). A special note must be made of its sense of world-building, as well. A key piece of exposition comes not from a David Mann voiceover, nor really from anybody talking to David at all. It comes from the AM radio talk show David is listening to in the car. It’s a bunch of dudes calling in talking about how they no longer feel like the man in their own homes. It’s another reason why the added scene with David on the phone with his wife is so unnecessary; anything that sequence might have established, Spielberg and Matheson have already baked into DUEL, practically in the background.

———

So, where does DUEL stand in the greater Spielberg canon? Well, it’s hard not to watch it without immediately reflecting on JAWS, a movie with the same general idea (swap out a truck with a shark and you’re already halfway there), although given the new brand of Hollywood polish that would go on to define the work of Spielberg and most of his contemporaries for decades to come. Funnily enough, this was the movie that made Universal realize that he was ready for a movie with the scale of JAWS, although there’d be another theatrical movie in between, THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS, which we’ll break down in full in two weeks.

More to the point, however, is that DUEL’s major legacy is as Spielberg’s first major shot across the bow. At just twenty-five years old, and after doing consistently solid work on television (including the first Columbo episode), he had shown that he was special in a way that not many others at the time were. In a world where TV movies could be a legitimate launching point for major filmmakers (i.e. an extinct world), Spielberg completely took advantage of the training ground he had been afforded. As mentioned, the only real issues with DUEL come from the script, and even those are easy to forget when taking the movie in totality. From a directorial standpoint, Spielberg already had the steady hand of a seasoned pro, establishing a character expeditiously, then putting him through the ringer in the way any average reasonable person could relate to, heightening the stakes all along the way.

All in all, DUEL isn’t quite a masterpiece, but it’s close. As it turned out, it didn’t need to be anything more.

In two weeks: 1974’s THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS!

Jabbin’ About JAWS: A New Summer Series!

This summer, we’re jabberin’ about JAWS! We start, as always, at the beginning. Let’s dig into the original blockbuster and why it stands apart from most of its contemporaries all these decades later.

One of the strange, ironic anomalies about American film in the 1970’s is that, mixed in with some of the strongest and most daring independent voices Hollywood would ever produce, the decade includes the definitive starting data points of where the industry stands now, a sequel-and-IP-driven industry that has done a ton to choke out those very same independent voices.

The same decade that gave us ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST, THE FRENCH CONNECTION, TAXI DRIVER, DOG DAY AFTERNOON, AMERICAN GRAFFITI, CHINATOWN, BARRY LYNDON, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE and, oh yeah, the first two GODFATHER films also gave us THE EXORCIST, ALIEN and the very first STAR WARS. Through those kinetic crowd-pleasers, we can track the birth of the “blockbuster” all the way to today, where we are practically drowning in Marvel and Lucasfilm streaming content (to almost inarguably diminishing returns).

Of course, the first “real” blockbuster, at least the one that popularized the term for all intents and purposes is Steven Spielberg’s 1975 thriller JAWS. Based off the 1974 Peter Benchley novel, JAWS was an immediate sensation, making $472 million against a $9 million budget, made generations of people irrationally afraid of sharks (on the whole, not that interested in people!) and, most importantly, sparked a major change in movie studio priorities. Slow-burn, expensive character dramas were out. Populist popcorn flicks were in, the more special effects, the better.

This, of course, feels like the absolute wrong lesson for studios to have pulled from JAWS. This is because, nearly fifty years on, after the movie no longer has any ability to scare you, so familiar are its tropes and beats, Spielberg’s first major break still stands out due to the actual legitimate character work that it does, giving us three fully realized human beings as the stars of the film, as opposed to a shark that ominously (and accidentally) is rarely seen onscreen.

It’s a JAWS summer, y’all! Let’s dig in.

JAWS (1975)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Written by: Peter Benchley, Carl Gottlieb

Starring: Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, Richard Dreyfuss, Lorraine Gary

Released: June 20, 1975

Length: 124 minutes

JAWS is a surprisingly difficult movie to talk about in 2022, if only because it feels like everything that can be said about it, has. It’s even a couple years older than the original STAR WARS, maybe the most single over-analyzed movie in the history of American film. JAWS’ troubled production history is well-documented, with its profound technical failures planting the seed for the movie’s single most important contribution to film: the ominous, minimalist score by John Williams serving as superior substitute for actually seeing the shark.

Compounding the issue, ironically, is the fact that JAWS still holds up! Oftentimes, big broad masterpieces like this speak for themselves, making it kind of difficult to break down what makes it fun without getting into the territory of the obvious (“the scene where the shark explodes was exciting!”). But I think it’s worth it to try, mainly since…well, I have to. It’d be profoundly weird to start a month-long JAWS series by skipping the one everybody has seen. But it’s also worth it to remind people that big ol’ blockbusters can still come with a considerable amount of craft behind them. JAWS also serves as a great way to advocate for arbitrary restrictions in film-making to allow for creativity to flourish.

JAWS is a movie that operates in two halves. The first half of JAWS feels like a broader character study of the psychological makeup of a small seaside town. Martin Brody (Scheider) is working his first summer as sheriff of Amity Island when he receives word that a young woman, Chrissy Watkins, has gone missing after going swimming. After her partial remains are found on the beach and a subsequent medical examination reveals injuries consistent with a shark attack, Brody finds himself in the middle of what is right and what is convenient. The beaches obviously have to be closed, but Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) stands in the way of this, since the upcoming Fourth of July weekend is the biggest of the year for the town’s economy.

The arrival of young oceanographer Matt Hooper (Dreyfuss) adds to the tension, as he deflates the excitement of the recent capture and killing of a large tiger shark that seemed to put an end to the vicious threat. He asserts, judging from the bites on the bodies, that the town is being terrorized by a great white, and Amity now needs to figure out what it’s going to do. Do we keep the beaches open, or close them? How do we end our shark trouble once and for all? Local fisherman and Captain Ahab stand-in Quint (Shaw) offers his expertise and services to kill the shark….if Vaughn will put up $10,000 as a reward.

Of course, the parallels between Amity’s reaction to an unseen threat endangering the economy and “our current times” can’t be ignored. In fact, it’s already been discussed in some detail over the past couple of years. Suffice to say, however, government officials valuing the safety of the economy over its populace, the dismissal of experts as nerdy kill-joys, the belief that a natural threat can be negotiated with or is interested in working on a human timeframe….it all would be aggravatingly on-the-nose if JAWS hadn’t predated current reality by over forty-five years. So, yeah, the emotions and motivations being tracked amongst our principals in Amity 100% track.

Act I of JAWS contains most of the movie’s super-signature moments. There’s that famous dolly zoom on Brody’s face as Alex Kintner bites the dust. There’s the infamous “that’s some bad hat, Harry” line that should sound familiar to anyone who’s watched an episode of House to completion. There’s that fisherman corpse jump-scare. And the scene where Brody pours himself an entire Collins glass of red wine. And that shot of Brody reading up on sharks, where we see him flipping through the pages via the lenses of his glasses, almost as if we can see him absorbing the information into his brain in real time. And, of course, we hear the iconic John Williams bass notes right in the opening seconds. On and on and on, it goes.

Although he didn’t get a Best Director nomination, there’s little flourishes like this that made it obvious the 26 year old Spielberg was someone to keep your eye on. And the movie often looks gorgeous. But it wasn’t just Spielberg that makes this first half sing. No, an equal amount of credit goes to the script, more or less cowritten by Benchley and Carl Gottlieb. Benchley did the first three drafts before tapping out and handing the script over to other screenwriters. He ultimately provided the plot’s structure and a lot of the “mechanics” of the sailing and oceanography. Playwright Howard Sackler (who was absolutely not one of those Sacklers, I already checked) did an uncredited rewrite, who focused in on characterization, including the crucial detail of Brody being afraid of water.

In an attempt to add some levity, Spielberg asked his friend Carl Gottlieb what he would change were it up to him. Three pages of notes later, he ended up becoming the primary screenwriter the rest of the way, with much additional dialogue pulled from improvisations generated from cast and crew dinners. John Milius provided some dialogue additions, and SUGARLAND EXPRESS writers Matthew Robbins and Hal Barwood did some uncredited contributions.

But all this work, and facilitation of multiple contributors, paid off. Why the first half of JAWS works so well is because the script deals with the fallout of the shark’s destruction honestly. As just one example, both Mayor Vaughn’s early insistence on keeping the beaches open and Brody’s ultimate reluctance to stand up to him, have deadly consequences. The aforementioned death of Alex Kintner serves as the turning point for Brody (although, notably, not a turning point for Vaughn, who I am convinced eventually became the President of the United States in the JAWS-iverse). In the fallout of the tense, brutal, pulse-pounding death of Kintner, and as the subsequent capture of the wrong shark is being heavily celebrated by the town, the movie still adds a touch that most movies nowadays might have skipped altogether.

Brody is approached by Kintner’s mourning mother who has nothing but a slap to the face and admonishing words for the sheriff. He knew the waters were dangerous, and that a girl had already been killed by whatever it is out there. And he let the beaches stay open anyway. How could he?

I think this is a scene that would have been excised for being too “dark” or something if JAWS were made today. After all, it makes us directly question the integrity of our lead character, something that legitimately might be considered too complicated to get into now. Because the thing of it is….Kintner’s mom is right. She’s not just an unfair obstacle for us to get upset at. Brody fucked up. Yes, yes, there’s the reflex of saying, “it’s actually Vaughn’s fault! HE’S the one who was forcing him to keep the beaches open!” Which is true. But the buck falls on the man whose job it is to keep people safe. And Brody knows it.

That’s why the moment resonates so hard. And it’s part of what motivates him from here on out.

For all that, though, the second half is really where the movie shines, and the fact that it works so well is a testament to how JAWS bakes in its exposition and character building through action. Brody, Quint and Hooper all band together to take Quint’s boat the ORCA out to kill the great white once and for all. Simply put, there’s nothing for the movie to set up about these three once they get on the boat. We’ve learned everything we need to know while we were busy being scared in the first half. Brody is the lawman who hates the water, Hooper is a steadfast and sarcastic expert, and Quint is the eccentric wild-card.

Notably, there are a few things two of the three characters have in common; for instance, Brody and Quint are the adults on the boat, while Quint and Hooper have the maritime experience (and scars to show for it) that Brody simply lacks. Most telling of all, Brody and Hooper don’t have the personal connection to a rogue shark that Quint ultimately does. But there’s nothing to unify the trio as a team as we set sail.

The real bonding moment between the three is Quint’s famous speech detailing the real-life horrors endured by the members of the U.S.S. Indianapolis, a moment that many have identified as the true heart of JAWS. This monologue, delivered during an otherwise quiet dinner between the three below deck, sets up the true terror inherent in a shark, maybe more than any other moment, sequence or visual in the movie. For those not familiar, the U.S.S. Indianapolis was a naval ship that was returning from delivering the initial parts of the atomic bomb before getting nailed by a Japanese missile. Those who survived the initial blast, however, found themselves sitting ducks for a series of brutal shark attacks. Of a crew of about 1,000, only about 300 survived.

It’s a harrowing, fucked-up story that’s just as chilling when you remember that it’s 100% true (also, it feels notable that the script changes the date of the sinking of the Indianapolis from July 30 to June 29, the same day and date of the fictional death of Alex Kintner). Thus, the decision to anchor Quint’s character as having lived through this real-life horror show makes his quest to kill the great white all the more understandable, perhaps the ultimate example of “raising the stakes” for a character.

What punctuates Quint’s speech even further in JAWS, however, is how the scene slowly transitions back to the three of them having drunken revels, banging on the table, singing sea shanties, and forgetting about their trouble ahead. Then, BOOM! The shark has returned and is pounding on the side of the ORCA. The danger detailed in Quint’s speech starts flooding back to the characters, and us, and the cost of failure has never felt so high.

The second half is also where all those clever work-arounds to cover for the mechanical shark not working come into play. As alluded to previously, one of the biggest, most famous pains in Spielberg’s ass during the making of JAWS was the fact that, among other things, the big mechanical sharks that had been created (in place of an actual trained shark, which was the original plan, holy shit) kept getting waterlogged and short-circuiting. I’d argue that Robert Shaw getting wasted all the time was as big of an issue as the shark, but I understand that JAWS is a hard movie to film without, you know, Jaws.

Brody, Quint, and Hooper eventually realize attaching buoyant barrels to the shark is their only chance at being able to keep tabs on its location. It’s a logical decision by the characters, and you figure, for the filmmakers, it’s a hell of a lot easier to control a bunch of empty barrels than it is a giant mechanical shark. However, this decision also sets up the barrels as the real visual signifier for us in the audience. It’s always cool when a movie works it out so a normal, benign object all of a sudden becomes terrifying.

JAWS barrels towards its exciting and famous conclusion, and it struck me that the movie is so self-contained (and, like many movies that are over thirty years old, just ends once it reaches its natural stopping point! No prolonged wrap-ups of subplots, no set-ups for potential sequels…the shark dies, movie over!) that I don’t even think I realized there were sequels to JAWS until I was a teenager. And that’s the sign of a great one. You can get off here, or you can keep driving down the Highway of Diminishing Returns. It’s up to you!

So why does JAWS not receive the same kind of world-ending ire that some of its other early blockbuster contemporaries do? Well, part of it is that it hasn’t watered itself down as much over the years. Yes, up until 2002, there were just as many JAWS movies as there were STAR WARS movies, which is bizarre to think about. However, the non-serialized format of the JAWS series has left its sequels as more obscure and less popular than its original, which allows it to stand above the rest of the series. This stands opposed to STAR WARS, where at least one of its sequels is arguably more beloved than the original (that sequel being, of course, THE RISE OF SKYWALKER).

Also, for whatever reason, JAWS has never been a property that anybody has tried to reclaim as fresh IP. We had the three sequels, one unofficial international follow-up/ripoff (okay, there are actually hundreds and hundreds, but only one that anybody really cares about), and…that’s it. No Saturday morning cartoon, no legacy sequel, no limited series on Peacock (at least not yet). Hollywood has, for whatever reason, seen fit to leave JAWS be.

Finally, I think JAWS is arguably the strongest of its imitators simply because of all the work they did to focus on human characters, so that when the shark starts snacking, we’re invested. It’s not quite the same thing, but it’s the problem that a lot of the American GODZILLA movies fail to understand, and I see audience expectations shifting in kind; I hear a lot of people say, “who cares about the humans at all? It’s a movie called Godzilla!” Well, actually, the human stories are vital for us to have an entry point into the destruction, but so often, movie studios want to cynically half-ass that part. Maybe because it’s hard? Maybe because it’s easier to pour money into the CGI than the writer’s room? Regardless, it would suit most studios to go back to the basics for awhile.

It’s a shame that, in the wake of JAWS’ undeniable success, the instinct was to replicate, and expand upon, the fireworks and thrills WITHOUT including the exquisite writing that makes everybody involved feel like a recognizable human soul, which only helps to increase the stakes. After all, what good is a shark eating somebody if I don’t care about them?

Next week: Brody and Mayor Vaughn return for 1978’s JAWS 2!

Best of

Top Bags of 2019

This is a brief description of your featured post.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sign up with your email address to receive news and updates.