CLOSE ENCOUNTERS and the Cost of Passion: SPIELBERG SUMMER Continues!

Welcome to Week Four of our first Annual Summer of Spielberg! This summer, we’re working our way through the 70’s canon of Steven Spielberg and we’ve reached yet another notable film in his then-young career that warrants much discussion.

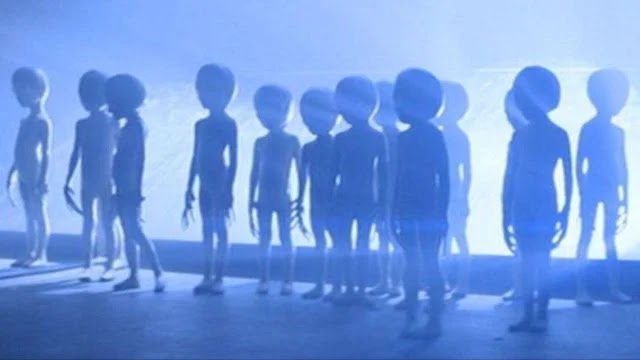

It’s an early Spielberg epic exploring humanity’s response to seeing colored lights in the sky, where people and animals begin disappearing from a sleepy town in Southwestern America, and true UFO believers become obsessed with proving their creeds to their families and loved ones. It all ends, as you remember, with first contact officially being made, and the true intent of our alien visitors being revealed.

I speak, of course, of 1964’s FIRELIGHT.

It was technically Spielberg’s “first film”, a distinction that could just as easily be made about 1971’s DUEL and 1973’s THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS. He famously made it at the age of 17 on a budget of $500, and even more famously turned in his very first profit after screening the movie for one night in Phoenix, AZ and making $501 at the box office (Spielberg figured in an interview with James Lipton in INSIDE THE ACTORS’ STUDIO that they got 500 people in the theater, charged one dollar a head, and someone must have ended up paying two, hence the profit).

The vast majority of FIRELIGHT is unfortunately unavailable to the public; something like three minutes of its semi-unfathomable 135-minute run time remains. On the other hand, considering the cast was mostly theatre students from the local high school, as well as Steven’s sister Nancy, one has to imagine three minutes is more than enough to pull whatever you need out of what is ultimately a curiosity, the Steven Spielberg movie before there were Steven Spielberg movies.

Everyone seemingly moved on after FIRELIGHT’s one-night-only release date of March 24, 1964. But Spielberg clearly never shook the idea of aliens visiting our world, a story borne from a lifelong obsession with unidentified flying objects and watching a meteor shower with his father. The reason we know he never shook it is because FIRELIGHT more or less got remade as an actual Hollywood-backed film, CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND. Only this time, there was way more pressure on Spielberg, who in the thirteen years since FIRELIGHT had made a genuine paradigm-shifting blockbuster in JAWS and was now being looked at to deliver once again.

And…he did! Spielberg managed to match the lofty expectations generated from his water-bound blockbuster and made a film that is much bigger in scope that JAWS ever was. It’s also much more melancholy in ways I had forgotten about. Most importantly, it’s a movie that reflects more of its creator’s obsessions and state of mind than maybe was even intended at the time.

Let’s do it! It’s CLOSE ENCOUNTERS time.

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND (1977)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Written by: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Richard Dreyfuss, Teri Garr, Melinda Dillon, Francois Truffaut

Released: November 16, 1977

Length: 135 minutes (theatrical version), 132 minutes (special edition), 137 minutes (director’s cut)

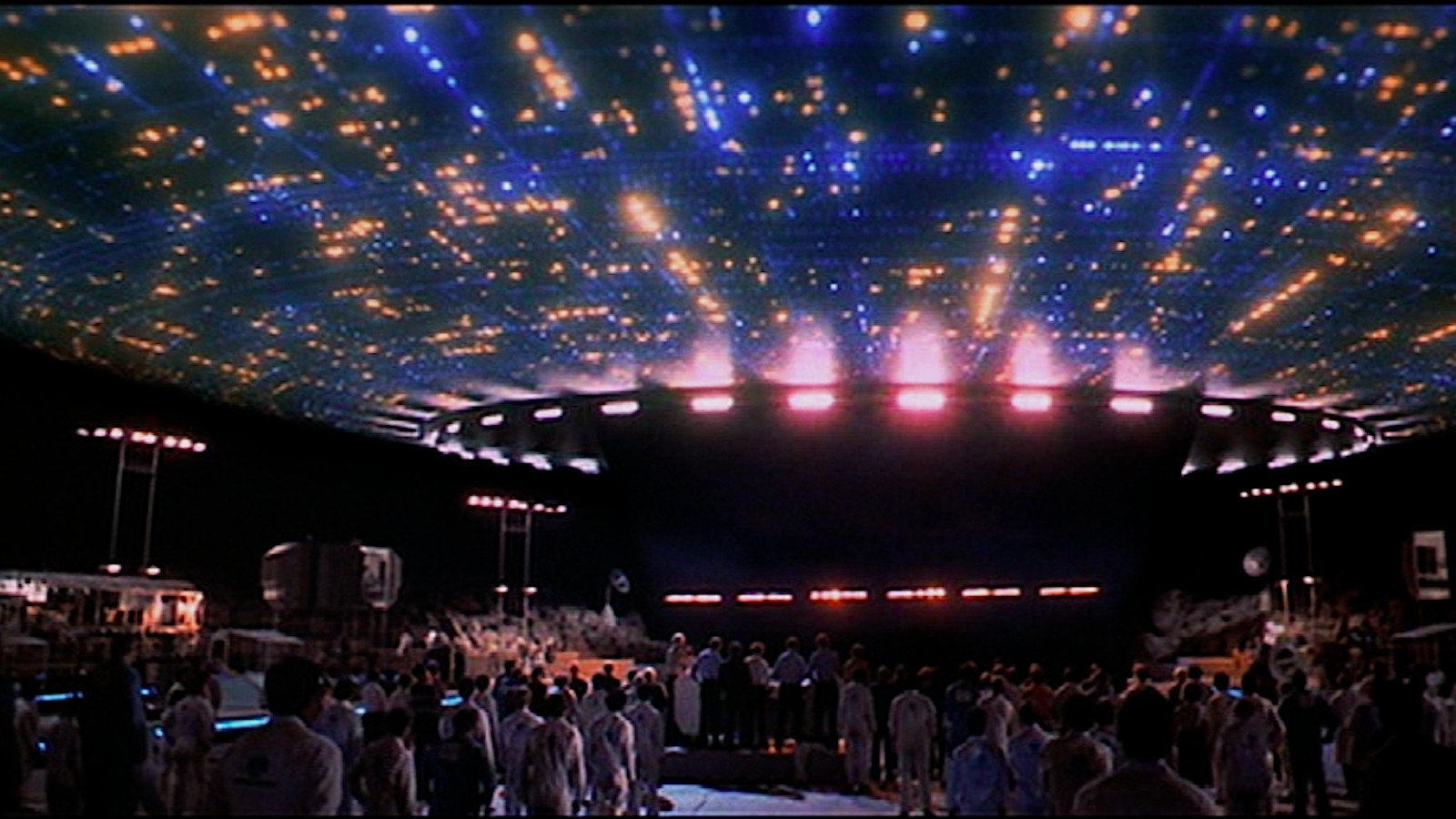

As one might imagine in a movie entitled CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, Spielberg’s fourth feature-length film, like many classic sci-fi stories before it, asks what might happen in a world where extraterrestrial beings finally reveal themselves to Earth. Its story consists of several threads that eventually weave together like a tapestry. There’s the tale of Roy Neary (Dreyfuss), who almost literally crosses paths with a UFO and becomes compelled to find it again. There’s Jillian Guiler (Dillon), whose little boy Barry is abducted by mysterious lights in the sky. There’s Claude Lacombe (Truffaut, the seminal French New Wave director making an extremely rare appearance in an English-speaking film), a representative of the French government who finds himself collaborating with the U.S. government on something incredible: establishing first contact. All parties will eventually find themselves in Wyoming, hoping to communicate with the aliens utilizing an established five tone sequence (you know the one, even if you think you don’t know it).

The most notable thing about taking CLOSE ENCOUNTERS sequentially is that, even though it’s not even close to being the first Spielberg movie, it may be the very first Genuine Spielberg Movie, one you’d be able to spot from a mile away. It has all the hallmarks one expects from his classics: we’ve got a fractured family (the Nearys), a lost child* (Barry), the wonders of space and the great beyond, benevolent alien beings, shadowy faceless government enemies and vehicles, and, most important of all, the Everyman selected by his circumstances to become the hero of an incredible story.

*Although, something I haven’t yet noted: essentially every one of Spielberg’s films prior to this have also included a missing child in some way. It’s more literal in THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS (the Poplins are trying to regain custody of baby Langston) and JAWS (the death of Alex Kintner), while in DUEL, the loss is more implied (David Mann’s family life is on the rocks). Steve’s been doing it from the beginning!

It’s all the more impressive that Spielberg was able to establish such a reliable template for himself when you consider how turbulent the movie’s creation really was. JAWS has taken up all the oxygen when it comes to “troubled 70’s Spielberg productions”, but CLOSE ENCOUNTERS did not itself have much of a smooth birth. Its initial conception goes back to 1973 as a film entitled WATCH THE SKIES, with Paul Schrader working on a first draft of the script. JAWS pushed everything back a year or so, and a major setback occurred when it turned out Spielberg fucking hated Schrader’s draft, eventually referring to it as “one of the most embarrassing screenplays ever professionally turned in to a major film studio or director”. Seems a bit harsh to me, but suffice to say, Spielberg and Schrader split over creative differences soon after. After several rounds of rewrites from folks like John Hill, David Giler and Matthew Robbins, Spielberg began taking a crack at the script himself, using the famous Disney song “When You Wish Upon a Star” as influence.

A couple of years later, once JAWS was in the rearview mirror and Spielberg’s alien project was finally ready to go, its producing studio, Columbia, ran head-on into financial issues. This already huge problem was exacerbated by the fact that CLOSE ENCOUNTERS’ budget grew exponentially. Spielberg had quoted the studio about $3 million in 1973; by the time its filming was completed, it sat at about $20 million. Lightning strikes and hurricanes destroyed much of the Alabama soundstages. A producer, Julia Phillips, eventually got fired for doing too much cocaine. Spielberg himself said the shooting experience for CLOSE ENCOUNTERS was “twice as bad” as JAWS, just to set the bar.

One of the seemingly biggest factors in the shoot being prolonged is the fact that Spielberg’s own vision for the film kept increasing in scope throughout the life of the movie, all the way up to and including its release. The production schedule kept lengthening as new ideas kept generating in Spielberg’s head, and he had issues defining the movie’s “wow-ness” in various cuts. Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond eventually had to drop out of reshoots due to other commitments (although a team including Douglas Slocombe took over, so perhaps everything worked out).

This all leads to one of the most famous aspects of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS: the existence of several cuts. The theatrical version was released in November of 1977, but Spielberg never seemed truly satisfied with the way it turned out. Despite having final cut privileges and a request to the studio for six more months, Spielberg agreed to have the movie released as it stood, only later leveraging its success to make a director’s cut in 1980. Famously, that director’s cut actually wound up being five minutes shorter, as he wound up going back and removing or shortening many other scenes (most notably the scene where Roy throws a bunch of bricks and dirt into the family kitchen), exercising an artist’s right to fuck with a completed work that his friend and colleague George Lucas would take to its absolute breaking point.

The Director’s Cut also features the addition of several minutes of footage, including an infamous, studio-mandated look at the insider of the mothership, a move that Spielberg regretted so much that it generated a third cut of the film, a VHS “Collector’s Edition” that included all the new and old footage, minus the mothership interior. There actually appears to be a fourth recut version floating out there, a syndicated television edition that was available on a 1990 Criterion Laserdisc.

(For what it’s worth, the version I watched was the theatrical version. It may be the only version I’ve seen. Maybe somewhere down the line, I’ll check out the other two versions just to say that I did. The Director’s Cut has its ardent supporters, up to and including the late Roger Ebert who called it better than the original. I just…man, Spielberg’s right, he shouldn’t have given in on the mothership interior. It seems so anti-imagination and, thus, anti-Spielberg. One of these days.)

The reason I bring all this extensive recut history up is that, whether he intended it or not, nothing could be more illustrative of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS’ main themes of single-minded obsession in the face of something extraordinary than this driving need for Spielberg to get the movie right. One can easily imagine him sifting through the footage of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS at various points of his life and looking much like Richard Dreyfuss hovering over those mashed potatoes. Hell, one can just as easily imagine him seeing that fateful meteor shower as a kid and getting that obsessive idea implanted in his head: “I have to tell this story.” He tries it once with FIRELIGHT, he tries it several times over several decades with CLOSE ENCOUNTERS, he comes back to it over and over in his filmography (picking it up next with E.T.). He keeps plugging away at that five-toned tune, hoping to finally make contact.

In that sense, you get more of Steven Spielberg’s psyche in Roy Neary than maybe he even meant to, which may be why subsequent editions tried to sand the edges off that particular storyline, even if said edges are just too jagged to ever be made smooth.

Oh yeah, that ending. I guess we should talk about that ending.

What really struck me about CLOSE ENCOUNTERS on this rewatch is just…how kind of sad the ending is, even a little bleak. Oh, sure, on the whole, the final half-hour or so is Spielberg firing on all cylinders. Humans and aliens slowly and successfully communicating via the usage of simple musical tones is pure Spielbergian fantasy (I mean this as a compliment). It’s thrilling and is perfectly paced, perfectly scored. It’s maybe the most parodied and memorable part of the whole film. Tonally and textually, the ending of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS is quite the crowd-pleaser.

No, I mean the way Roy Neary’s story actually concludes. Neary’s journey is, of course, the backbone of the entire picture. To recap, he is a lonely electrician who is merely in the right place at the right time to get an up-close encounter with a UFO. From then on, he becomes singular-minded and obsessive about an undefined shape. He sees it in his pillows, he draws it on his work notes, he famously builds it at the dinner table with his mashed potatoes.

The shape is revealed to be Devils Tower in Wyoming, the agreed landing spot of our alien visitors, the area where first contact will officially be made. Roy eventually begins to make his way over to Wyoming in order to fulfill his new destiny, but not before successfully scaring off his wife and kids. Prior to his departure to Wyoming, a morning of throwing bricks and dirt into the kitchen is enough to cause his wife Ronnie (Garr, in peak heartbreaking form) to take the kids to her sister’s for a while.

As I had correctly recalled, the movie ends with Roy being chosen by our alien visitors to come back with them into space, where he’ll be able to embark on the most incredible adventure any human could ever imagine being on. What I had forgotten, however, is that the scene of Ronnie leaving for her sister’s is the last time we see her or the kids in the movie ever again. There’s no resolution beat at the end where Ronnie realizes her husband was correct, no cut to them catching up with this incredible event over the broadcast news, no nothing. Frankly, positive resolution between Roy and Ronnie may not even be a realistic thing to hope for; I turned to my wife at the end of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS and asked her, “if I had all of a sudden starting acting like a lunatic, obsessed with a location and convinced aliens are speaking to me until you literally left the house, would it matter at all if I was later proven to be 100% correct in my beliefs?”, her immediate answer was “no”. It’s reasonable to believe Roy never sees Ronnie or his children ever again.

But then, such is the Great Theme of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS, that of single-minded devotion and obsession, bordering on religiosity. No matter what happened in their lives previous to the movie’s start, all of our principals have undergone a soul-rattling, magnificent experience. From the second the spaceship first arrives, the lives of Roy, Claude, and Jillian (and many nameless others) have diverged from their relatively normal paths. They are now responding to a higher calling, not unlike the many in history who have turned their backs on their loved ones and the lives they had built in order to better devote themselves to God, shaving their heads and vowing poverty and charity.

So, yeah, although it’s a wonderful and uplifting ending in terms of tone and texture, it’s difficult to call the conclusion of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS overall “happy”. The lives of those left behind have quite literally been ruined, or at least altered irrevocably. Subsequent editions have tried to trade out some of Roy’s crazier moments for scenes that play with more sympathy (like him breaking down inside his shower, for instance). But, it’s hard to edit or tinker around the fact that Roy ditches his life and loved ones to pursue a higher calling. It’s magical and devastating in equal measure.

In that sense, CLOSE ENCOUNTERS seems to be a story of emerging genius (and how closely it can be linked to genuine insanity), and I don’t think it’s an accident that this is the version of the UFO story that emerged once Spielberg took over the script himself. It’s also not surprising to me that Spielberg seemed to struggle with articulating it all, going back and tinkering with it two or three times. It’s sort of a movie about Spielberg at this time in his life, having changed Hollywood irrevocably and forging his path as an industry great while barely entering his thirties. Not that Spielberg broke the hearts of all of his loved ones in order to make fucking JAWS or anything, but there’s the feeling of truth to how Roy is drawn by a higher power to this jaw-dropping turn in his life.

That’s the power of lights in the sky. And meteor showers. And getting all your friends together to make a too-long movie that earns your first dollar. It just may trigger something in your brain and soul that kicks off a lifelong passion.

And the world may change along the way.