THE LONG GOODBYE Reveals the Folly of Caring

The pantheon of 70’s New Hollywood pioneers is vast. Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Peter Bogdanovich, Elaine May, yes even you, George Lucas…these are just the names I’m coming up with off the top of my head (and that’s just limiting the list to directors; if we opened this up to writers/cinematographers/producers….oh boy). However, none were quite as hugely influential yet somehow a little under-appreciated as Robert Altman.

For everything he was famous for (his ability to work in seemingly any type of genre; his naturalistic, improvisational style of dialogue; his knack for running counter to every American film style of his time) perhaps Altman’s most impressive trait was his consistency in output. Despite his relative late start (although he had done a ton of television work, he didn’t make his first movie until the age of 32, and his first major one wasn’t for ten years after), he managed to remain insanely prolific, basically releasing a movie a year all the way up until his death in 2006. It should be mentioned that he did it without much in the way of accolades from his industry; although he was nominated for a handful of Oscars over the course of his thirty-year career, he never won one, save for an honorary award after his passing.

Through it all, he remains a formative influence on several generations of working filmmakers and budding cinema aficionados. Yet, I really had only seen a couple of his thirty-five (!) movies, and most of those had only come in the last year or so. Well, no longer! Although a full career retrospective was a little intimidating (that would essentially be my entire year), I did want to take the next few weeks to be able to dig into this first decade of work.

First out of the gate is a subversive noir riff that seemed to be under-appreciated at the time of its release. Luckily, it’s gained a significant amount of clout (clout amount) in recent weeks, with its star doing the rounds here in California for its fiftieth anniversary. And it just so happens to be a film I’ve been wanting to knock off my list for a long time…

THE LONG GOODBYE (1973)

Directed by: Robert Altman

Starring: Elliot Gould, Sterling Hayden, Nina van Pallandt, Jim Bouton

Written by: Leigh Brackett

Released: March 7, 1973

Length: 113 minutes

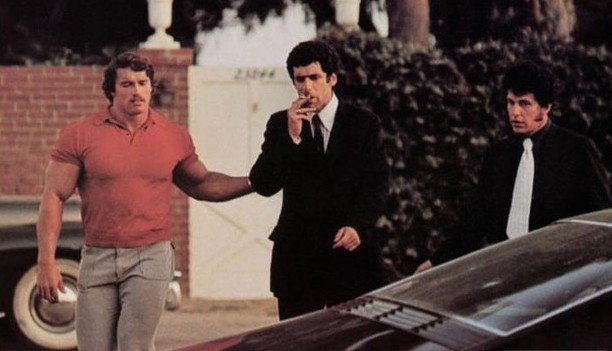

Like all detective stories, the plot of THE LONG GOODBYE is deceptively simple. After accepting an offer to drive his friend Terry Lennox (Bouton) across the border, private eye Phillip Marlowe (Gould) finds out from local authorities that Terry has been accused of killing his wife. Three days later, it gets reported that Terry has committed suicide. Marlowe doesn’t believe any of it. Thus, he plunges into sunny 70’s Hollywood to unravel the truth of the fate of his friend.

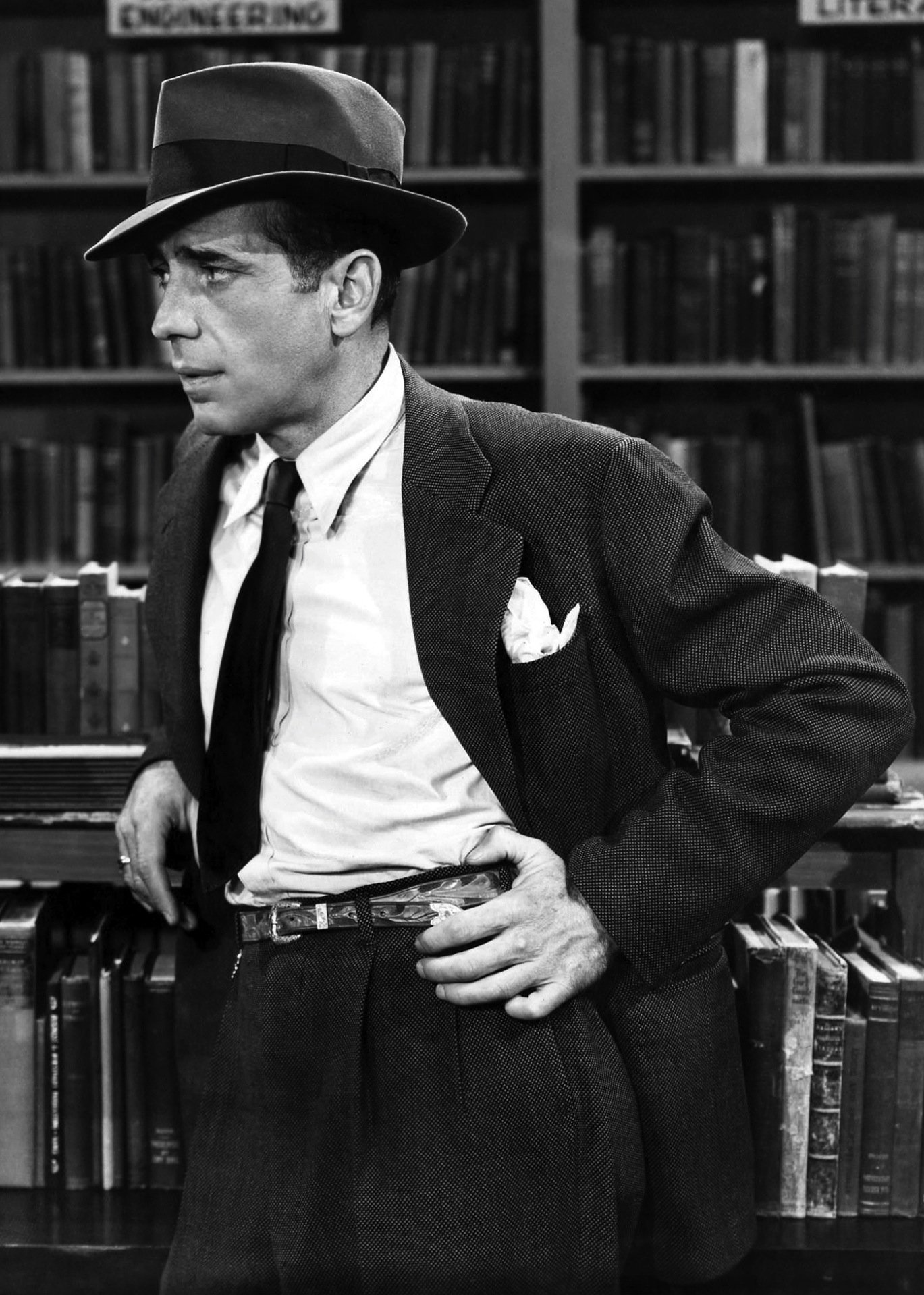

I should mention off the top that Phillip Marlowe is a character I admittedly don’t have a long history with, so this isn’t going to focus too much on comparing the various versions of the character that have appeared on both page and screen, the most famous by far likely being Humphrey Bogart’s turn in 1946’s THE BIG SLEEP.

Suffice it to say, however, that when most people imagine Phillip Marlowe, it’s difficult to shake that aforementioned classic “film noir” portrayal. A handsome, if sensitive and world-weary, gumshoe who may be wearing a tan trench coat or a pinstripe suit, tersely throwing out hard-boiled dialogue and navigating a tight, taut mystery, all the while effectively moving his way towards the truth.

That’s not the kind of character Robert Altman was interested in exploring in his film adaptation of the 1953 Marlowe novel, Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye. So….what did he want to do?

Right out of the gate, there are signifiers that THE LONG GOODBYE wasn’t going to be a companion piece to THE BIG SLEEP. For one, it’s set in the “modern day”, i.e. the 1970’s. For two, our lead is Elliot Gould, a man whose presence doesn’t exactly scream out Classic Hollywood.

The opening sequence of THE LONG GOODBYE serves as good a statement of purpose for the whole film as anything else. Put yourself in the shoes of the audience back in 1973 for a second. Outside of 1969’s MARLOWE (starring James Garner as the titular detective), there hadn’t been a big-screen adaptation of a Marlowe novel in over twenty-five years. And now here’s one by the guy who did M*A*S*H! Cool. So, how is this pioneer of this new era in Hollywood going to establish his vision of one of the most famous movie detectives of all time?

Well, over the first ten minutes of the movie, Phillip Marlowe’s main conflict is that he has to go the store and buy food for his cat.

It’s a bold, if inauspicious, introduction to one of the more famous detectives in Western fiction. But it’s hard to imagine any other way to kick this particular version of this particular character off. What better way to put a stamp on your modern version of a beloved gumshoe than by providing us essentially a short film of him just kind of walking around?

The beautiful functionality of pretty much all Altman films I’ve had the opportunity to see is that they are all entire islands unto themselves. War-torn Korea (that’s really a reflection of war-torn Vietnam). Snowy Washington at the turn of the 20th century. The music industry in 70’s Nashville. Popeye Village. Each of his films present entire and complete worlds that we are afforded only a precious few curated hours to spend within.

So it goes with THE LONG GOODBYE. This time, we get a deceptively cynical view of “modern” Hollywood. Not the “dream factory”, but rather the city itself. The movie sometimes looks pretty, but in an empty way.

In the middle of it all is this anachronism of a man, a dime-store lead of a detective novel dropped into a city in transition. It’s clear right away that he doesn’t quite belong where he is, and it’s not entirely clear how he got here in the first place. Notably, he’s the only character who smokes.

It’s why the opening reel of THE LONG GOODBYE is such a thrilling watch. Although it is loping and sprawling (and not unbroken, it should be stated; intercut through his quest to feed the damn cat is the arrival of Terry Lennox, kicking off the plot proper), it reveals a lot of character details about our lead detective. He lives alone, although his neighbors all seem familiar with him. He’s notably no stranger to being up in the middle of the night. He’s a cat person (fittingly, he’s revealed later on to have a real aversion to dogs, and vice versa). His cat has a preference in his dinner food, and it just happens to be the kind Marlowe doesn’t have. He’s cordial to the people around him, but he’s ultimately in his own Marlowe-world.

Sure, Marlowe may not have a ton of social skills, or have a woman in his life (I found it perfectly in character that he lives across from an apartment full of topless college girls, and he never makes anything resembling a pass at them), or appear to think about maybe stocking up on Courry brand cat food.

But he does appear to care that his friend has died under circumstances that don’t seem to add up. This is enough to set him apart from pretty much every person he comes across.

This brings us to one of the peculiar quirks of THE LONG GOODBYE’s “detective mystery” format. In this instance, our lead detective appears to be the only character to have any interest in solving the central mystery. Everyone else he meets along the way to solving the Terry’s murder seems to be in the midst of their own distinct incidental plot line. Marty Augustine just wants his money. Roger Wade just wants to keep maintain his explosive alcoholism by hiding away at a celebrity detox facility for days at a time. Dr. Verringer just wants his money. Eileen Wade turns out to just want to maintain her affair. The Mexican authorities just want their money.

On and on it goes. THE LONG GOODBYE is structured much like a video game fetch quest, except the game never threatens to progress and nothing is gained. It’s not an accident that many of Marlowe’s very best lines are delivered while talking to himself.

This all sounds like a recipe for a very frustrating watch (after all, why watch a mystery story where nobody wants to solve the mystery?), but it’s actually part of the movie’s true power. Although Gould plays him as a man whose emotions are kept inside, Marlowe eventually erupts at the revelation of the police knowing “who did it” and just hadn’t bothered to tell him. In this moment, all the false starts and sidetracks make his righteous indignation all the more cathartic.

Marlowe is more or less punished for caring, maybe the least cool thing you can possibly do in this part of California. This gets reinforced when (SPOILERS!) he finally tracks down his former friend, alive and well in a Mexican villa. Roger explains it all: he’s killed his wife and is probably going to get away with it because he’s legally dead. Marlowe offers another theory:

“Nobody cares but me.”

“Well, that’s you, Marlowe. You’ll never learn, you’re a born loser.”

“Yeah, I even lost my cat.”

In the films’ closing seconds, as he puts a plug into Terry’s chest, and as he walks away from the whole mess (walking right by Eileen driving by in a car), Marlowe appears to be a man unburdened. Whether this portends a happy or ominous future is up to the individual.

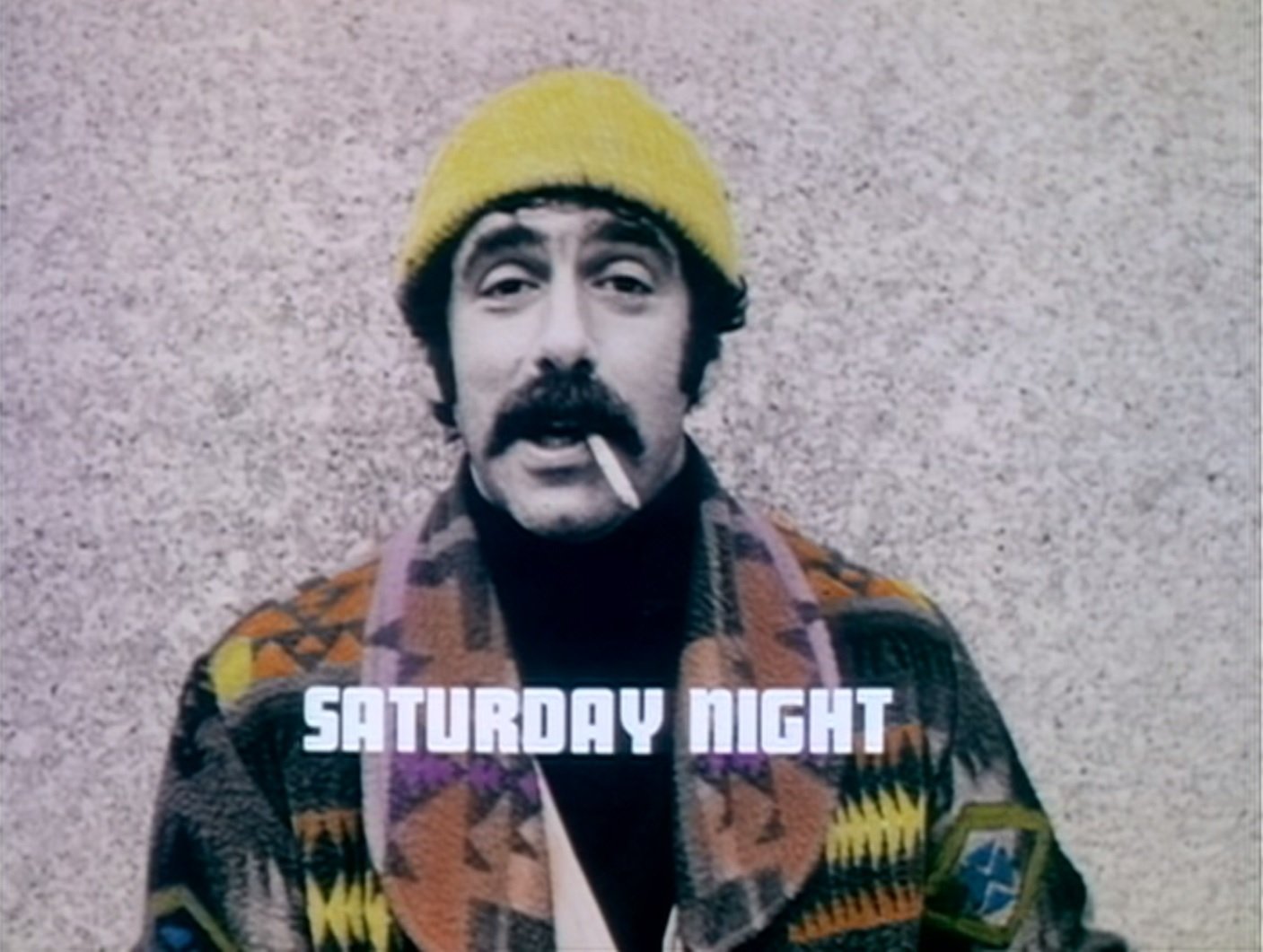

I couldn’t let this article pass by without gabbing about Gould. He’s somebody that I hadn’t really taken much stock of until recently. He’s not somebody whose movies I’ve taken a deep dive into, although there were two that were on a lot in the house in my formative years. One is a previous Altman collaboration that I’m going to defer discussion of for now (more to come!), and the other is the first Steven Soderbergh OCEAN’S ELEVEN movie, where his trademark delivery and voice provide some of its very best moments (“I owe you from the thing with the guy in the place, and I’ll never forget it…”)

But where it really hit me about my emotional connection to Gould was his appearance last year on Saturday Night Live, during John Mulaney’s go at a Five-Timers sketch. Because where I really got to see his full range of talents on display was during his many, many hosting stints during the first few years of SNL. He holds together the famous Godfather Therapy sketch. He was the dastardly network suit in the Last Voyage of Star Trek sketch. And, just so you all are aware, he was doing the “tap-dancing during the monologue” thing decades before Walken started doing it.

Compare all of that goof-around-ery with the very poised, nuanced and interior performance he gives here, and one has to wonder if Gould arrived at the precise wrong time in Hollywood. After Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice in 1969, it appeared that his superstar window had closed by 1973. How someone who seemed so of his time yet distinctly old-fashioned could be ever-so-slightly displaced in the industry is curious. On the other hand, it allowed to do quirkier work like this, and he remains beloved now, so I guess it all worked out.

There’s another old star in THE LONG GOODBYE that I would be sad not to highlight. Sterling Hayden is in a good chunk of this, and he’s phenomenal as always. I’ve always been in love with his singular energy and presence, and I’ve had difficulty expressing exactly why. Maybe it’s because he gives the type of performances that only come from “normal people” that get plucked into Hollywood basically by accident (I remain convinced a lot of what made him unique would have been beaten out of him in an acting school). He’s a little stiff, and in some of his earlier films, he sometimes looks a bit uncomfortable in front of the camera. But he draws you in like almost no other actor I’ve ever seen, past or present.

Same deal here. Maybe it’s his very specific voice timbre, a skill he puts on glorious full-throated display as the incorrigible Roger Wade. Maybe it’s his ability to make bad men heartbreaking, his vulnerability incongruous with his old-school handsome looks. Maybe it’s because his name is Sterling. For whatever reason, I’m always excited when he turns up in a film.

Leigh Brackett is credited with the screenplay for THE LONG GOODBYE, although given Altman’s improvisatory, overlapping nature that appears to be on display throughout here. Brackett’s hire seems like a “bridging the gap” moment; Brackett made her name early in life writing mystery novels very much in the vein of Raymond Chandler. She then pivoted to writing science fiction screenplays; her last work before passing away was an early draft of THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK (I’d like to think she’s a big unheralded reason why the quality of dialogue takes a dramatic step up between Episodes IV and V).

But her most famous work is undoubtedly the script to….1946’s THE BIG SLEEP! It’s difficult to tell exactly what her specific contributions were, nor how much of it was kept once the cameras started rolling. But I feel relatively certain that she was likely a guiding force in maintaining Phillip Marlowe’s anachronistic feel. The smoking, the outfit, the loneliness, the hard-boiled asides to himself: this all feels indicative of what an noir detective should feel like.

THE LONG GOODBYE was not exactly universally beloved upon its initial release. The reframing of the Phillip Marlow character was (and remains) atypical, and I don’t get the impression everybody cottoned to the concept of making him a sunny loser. Elliot Gould was also in a unique place in his career, where his particular presence and talents precluded him from quite becoming the A-list star that he seemed to be becoming earlier in the late-60’s.

In the other hand, Pauline Kael and Roger Ebert (the only two film critics that ever mattered anyway) got it immediately. Ebert described this version of Marlowe as “thrust into a story were everybody else knows their roles; he wanders clueless and complaining, and then suddenly understands exactly what he must do”. As for Kael, she put it thusly:

Gould’s Marlowe is a man who is had by everybody — a male pushover, reminiscent of Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity. He’s Marlowe as Miss Lonely- hearts. Yet this softhearted honest loser is so logical a modernization, so right, that when you think about Marlowe afterward you can’t imagine any other way of playing him now that wouldn’t be just fatuous.

Thus is the power inherent to a Gould-Altman team-up. Needless to say, I loved THE LONG GOODBYE. And it made me curious to revisit one of the only other Altman movies I had seen. Hell, I practically grew up with it…

Next week: we’re off to Korea!