Recent Articles

FOUR WEEKS OF MAY: ISHTAR

We’ve arrived at the end of Elaine May Month, with one of the most infamous debacles in Hollywood history, ISHTAR. Does the movie deserve its ragged reputation?

It seems like once every decade or so, there’s a major motion picture that ends up making such questionable creative decisions, weathering such tremendous behind-the-scenes drama, and enduring so much negative press that they become “Worst Movie Ever” contenders almost immediately upon release. In the 90’s, it was probably Rob Reiner's famous debacle NORTH. In the 2000’s, you couldn’t avoid hearing a joke about Ben Affleck’s GIGLI . And I’m willing to bet most people heard about the disaster that was 2016’s SUICIDE SQUAD long before they ever got around to seeing it, if they ever did at all.

The funny thing about those once-every-ten-years catastrophes is that those Worst Movie Ever tags eventually start to feel like foregone conclusions, rather than something the movie in question truly earned, an end result of press outlets needing a final punchline to the film they had spent months trashing. That is to say, it wouldn’t be very satisfying to roast BATTLEFIELD EARTH and then have it come out and be just mediocre, would it?

Well, in the case of BATTLEFIELD EARTH and stuff like SUICIDE SQUAD, the moniker ended up being apt. But for some of these others? They’re usually not great, but calling something the “Worst Movie Ever” before it’s even released is usually writing a check the movie can’t actually cash.

We also live in an era where movies that were initially critically derided and financially ignored wind up eventually getting revisited and often championed by future cinephiles. Off the top of my head, a short list of movies I’ve seen get reclaimed over the years include SPIDER-MAN 3, JINGLE ALL THE WAY, STAR WARS: EPISODES 1-3, THE VILLAGE, POPEYE…and ISHTAR.

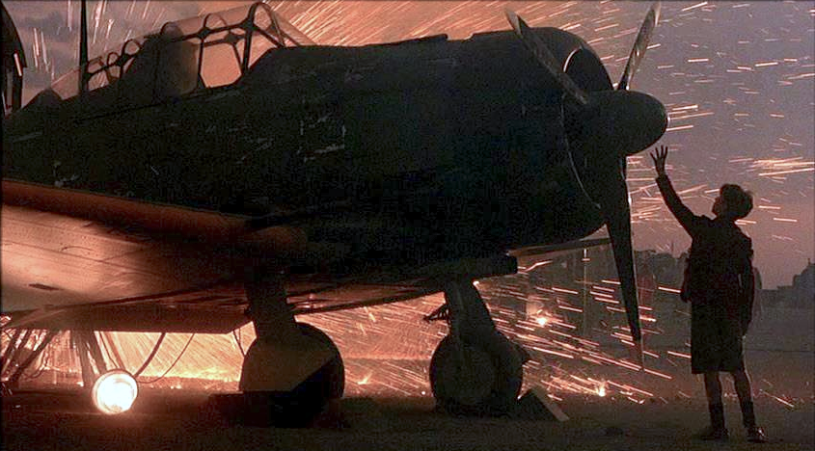

Ah, yes, ISHTAR, the movie that seemed to symbolize Hollywood failure more than any other when I was a kid. It felt like I heard it referenced a lot; I have a very specific memory of an Animaniacs episode set in a video store where a VHS copy of Elaine May’s final directorial effort was dropped to the floor, causing a nuclear explosion offscreen. Of course, I had never actually seen it; by the time I was old enough to have heard of it, it was almost ten years old. And the idea of watching a movie starring two men in their fifties wandering around in the desert didn’t sound that exciting to adolescent me.

But, as it happens, I have now seen ISHTAR, thanks to this self-imposed Elaine May marathon I’ve now completed. I find myself at a crossroads, trapped between two generation of cinematic evaluation. Is ISHTAR indeed an excessive unfunny attempt at comedy? Or is it in fact an under-appreciated romp?

In order to close out Elaine May Month, let’s find out!

ISHTAR

Directed by: Elaine May

Starring: Warren Beatty, Dustin Hoffman, Isabelle Adjani, Charles Grodin

Written by: Elaine May

Released: May 15, 1987

Length: 107 minutes

ISHTAR is the story of two very bad songwriters, Chuck Clarke (Hoffman) and Lyle Rogers (Beatty) that both manage to find each other and proceed to write terrible songs together in order to pursue their ambitions of becoming a famous singing duo. In an effort to scrape up work for them, their agent Marty Freed (Jack Weston) books them a gig in a Marrakesh hotel; as it happens, there’s an opening in the lineup due to recent political unrest. With nowhere else to turn, Chuck and Lyle head to Morocco.

Their flight takes them as far as neighboring Ishtar, where Chuck runs into a mysterious, desperate woman who claims her life is in danger and needs his passport. His decision to do so sets off a chain of events that takes us to the end of the film. Chuck and Lyle end up entangling themselves with the CIA, and find themselves in the middle of a complicated scheme to unseat the current Emir of Ishtar. Secret identities, double-crosses and good times with weapons ensue.

This complicated, yet simple, plot was meant to be an intentional riff by May on the old Bing Crosby-Bob Hope ROAD TO… vehicles, where the two stars usually played silver-tongued conmen who find themselves tossed around to faraway lands, and typically tended to be meta-riffs on popular genres of the time (desert adventure or jungle films, for instance). In a meeting with Beatty, May pitched her idea of doing a variant on that old series, set in the Middle East and starring Beatty.

I found Beatty’s appearance in this movie curious, since it didn’t seem like his kind of role, bordering on miscasting. It turns out that he was returning a favor to May, who had done extensive uncredited rewrites on REDS, as well as being the co-writer on the script for HEAVEN CAN WAIT. He decided to move forward with ISHTAR after he believed himself capable of providing the kind of protection May never had between her set and her studio.

Hoffman wasn’t as easily sold. As it turns out, his initial involvement was also as a result of a movie May had done uncredited rewrites on, 1982’s TOOTSIE. After eventually turning down ISHTAR, he’d go on to give May another shot, and met with her and brought along his creative consultant, playwright Murray Schisgal. They both felt that the movie shouldn’t leave the initial New York setting, believing the Morrocan stuff to overwhelm the rest of the film. Although he was hesitant, Hoffman ended up only doing the film after Beatty convinced him May would make it work.

In a fashion sadly typical of Elaine May films, the shoot quickly became chaotic. Columbia already had quick trigger fingers due to May’s reputation from MIKEY AND NICKEY for shooting much more film than is typically needed.

Many of ISHTAR’s behind the scenes issues were beyond their control. The decision was made to shoot the majority of the film in the actual Sahara Desert, and principal photography began just as Israel began bombing Palestine; the infamous murder of Leon Klinghoffer soon followed. Talk about your bad timing. There were also issues stemming from cultural differences between the American film crew and the Moroccan locals; there’s an infamous (possibly untrue?) story about one of the animal trainers dragging his feet on purchasing a blue-eyed camel, only to find out the camel was eventually eaten by its owner. Also, Morocco understandably didn’t really have the infrastructure to support a Hollywood film crew, and thus were unable to fulfill many requests and obligations.

Finally, Elaine herself seemed uncomfortable in the desert setting, and ended up fighting with people constantly. Some of her targets included: Warren Beatty, her cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, Warren Beatty, her editing crew, and Warren Beatty. Seriously, May and Beatty fucking hated each other by the end of this thing. Beatty felt like he was stuck on this shoot that was spiraling out of control because he had been doing it as a favor to a friend, yet he found himself disagreeing with May on almost everything. The budget ballooned, the release dates were delayed, and a public catastrophe was born.

As they often say, the story of what went wrong is twice as interesting as the product on-screen. The interesting and fraught friendship between Beatty and May takes this tragic arc that someone is almost definitely try to dramatize in a terrible prestige miniseries eventually. Maybe the people who brought us THE OFFER can take it on.

Well, enough about what went wrong behind the scenes. Was it all worth it? Was the initial dog-piling on this movie fair? What’s the tale of the tape?

Well, I regret to report that I didn’t like ISHTAR very much. I certainly don’t think it belongs on the Worst Movies Ever list; I’m not even sure it registers on the scale. But it is easily the least of May’s four directorial efforts and a strange misfire coming from someone who had such success at trying different genres and styles of films.

I didn’t go in wanting to hate it. I really did want to join the throngs that have sung the movie’s praises in recent years. But it turns out that I couldn’t, and it’s for one specific, overriding issue.

ISHTAR’s primary sin is that it just isn’t very funny.

There are moments here and there; I think the Paul Williams-penned songs succeed in their intentional ineptitude, and I greatly enjoyed how each Rogers and Clarke song is usually just a half-syllable off in meter, which causes it to hit the ear so badly. It’s also always welcome to give Charles Grodin a few moments to do his Grodin thing (although not nearly enough).

Finally, and crucially, I generally actually liked the characters of Rogers and Clarke. The way that they’re set up in the opening minutes (two inept songwriters who find each other almost by accident and end up losing their lives and savings as a result of their misfired ambitions), it seemed like a different movie entirely was in store. They’re broadly funny without feeling unmoored from reality. I would have been perfectly content if they had just stayed in New York and try to make it big (in this and this alone, Hoffman and I share some common ground).

Alas, we’re out of the United States by the twenty minute or so mark, and we arrive in the fictional Ishtar, on their way to Morocco to head to their first paid gig. Comedic hijinks ensue and they almost all fall flat onscreen. I can’t quite put my finger on why nothing seems to work, but work they do not.

I keep thinking about how Elaine May meant for this to be a tribute to the ROAD TO movies, a noble pursuit that somehow seems to have gotten lost somewhere down the line. I’m not the world’s foremost expert on those Hope and Crosby vehicles, but I can say that the best of the ones I’ve seen, ROAD TO MOROCCO, stood out from the others due to its actually quite catchy tunes and its wildly playful sense of humor; Hope and Crosby continuously make jokes about themselves as people, including their contract status at Paramount and their desire for Academy Awards. It’s a blatant break in character, but the actual characters don’t really matter in ROAD TO… films. Nor do the plots, as they’re usually merely flimsy excuses to get the pair into the next set-piece, usually involving Dorothy Lamour (Hope and Crosby usually comment on the thinness of the plots as well).

ISHTAR seems to have landed on the opposite philosophy, working very hard to establish Hoffman and Beatty’s characters (to some significant degree of success, as mentioned above) as well as an increasingly complicated plot. None of the trademark playfulness that one might expect from a ROAD TO riff is present here. It’s a little surprising to me that May replaced that with spectacle (that being said, Dustin Hoffman DOES fire off a rocket launcher in this, which is something), since her improvisation background would seem to be a great fit for that comedy style.

As a result, I find myself unable to reclaim ISHTAR as a slept-on classic. Instead, it’s merely a sad end to a far-too-small directorial body of work from one of the funniest people on the planet. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that Elaine May never directed anything else again. However, her legacy is definitely secure, having just this year received an honorary Oscar. She has a resume full of creative credentials longer than just about any other living person in Hollywood.

I don’t blame her for not returning to the director’s chair. Would you?

FOUR WEEKS OF MAY: MIKEY AND NICKY

Elaine May’s third feature is a quiet character-driven masterpiece, despite all the chaos behind the scenes that ran May from the director’s chair for another decade.

My “film journey”, for lack of a less pretentious term, started relatively late in comparison to others in my circles. In fact, I’d argue that it only really got going in earnest a couple of years ago.

Of course, I’ve been watching movies my whole life. When I was a kid, my mom showed me the big works of Disney, Spielberg and Lucas as well as select viewings of Classic Hollywood and pre-code stuff. My grandma opened me up to the comedic charms of the Marx Brothers, Abbott and Costello and the Three Stooges. Between me and my collection of friends, we covered most of the major blockbusters and Oscars bait that the late 90’s and early-mid 2000’s could offer.

But I’m not sure that I really dug into movies as something serious to study until the very recent past. True, I devoured trade magazines like Entertainment Weekly, and dutifully watched Roger Ebert and the villainous Richard Roeper every Sunday night. But this was really more of a way to stay on top of what was coming out, and what movies seemed to be trending upwards or downwards. It wasn’t a way to check out what had come before, or even analyze why I liked what I liked. It was just knowledge, nothing more.

There were several reasons for this paucity of actual viewing experiences. One of them was that watching the classics could be difficult, especially if it was a foreign film, as it often necessitated a trip to the video store and hoping for the best (Netflix’s “DVD by mail” service helped immensely in this regard). The primary reason, however, was that I went through a prolonged “anti-pretension” phase that kicked in around mid-high school and extended itself through, I dunno, like my early thirties or something.

It basically went like this: For the first third of my life, I hesitated to really dig into something that I knew was a passion of mine, lest I come off as a smart-ass know-it-all like the rest of the smart-ass know-it-alls I knew. Of course, this failed to account for the fact that this kind of “fuck the elitists” posturing was itself a form of pretension, the belief that your opinions were simply better than everyone else’s (this also leads very easily into living your life as just the devil’s advocate. People like this thing? It must be shit. I like something? It must be an underrated masterpiece, even if the thing I’m talking about is Spider-Man 2).

Anyway, by the time I hit 30, it dawned on me that, as a result of this kind of time-wasting, there were a lot of classics I just hadn’t seen. There’s still an embarrassingly long list. Even worse, a lot of the friends I have now are very smart film buffs that I just couldn’t follow along with or add to in conversation, the result of years of burrowing into my already-established interests, rather than expanding them.

To make matters even more devastating, I had discovered the much-beloved, now-defunct streaming app Filmstruck much too late, essentially after it had already been discontinued by Warner Media. Here it was, a streaming site that had put selections from the Criterion Collection and Turner Classic Movies potentially at my fingertips for a couple of years and I squandered it, completely unaware it was an option until it was already gone. It’s a terrible thing to find out about retroactively. An easy-to-access doorway to film history and I had blown it.

Enter The Criterion Channel.

For the unfamiliar, it’s what it sounds like: a streaming channel curated by the people behind the Criterion Collection, a pseudo-successor to Filmstruck. At the beginning of 2019, the launch of the app was announced, and an advance mailing list was opened up to the curious. As a lead-up to the app’s launch, a Movie of the Week program was announced. This way, potential subscribers could enjoy a single movie on the prototype platform, typically a movie that would give one an idea of the kind of programming the Criterion Channel would eventually house. I eagerly signed up, not wanting to miss another opportunity. This way, at least it seemed to me, I could start my film education in earnest, one week at a time.

First movie up? MIKEY AND NICKY.

It’s fair to say, then, that this week’s movie is responsible for my curiosity being stoked, and is responsible for the last few years of articles. Feels relevant, then, to revisit it again now for Elaine May Month.

Let’s get started.

MIKEY AND NICKY

Directed by: Elaine May

Starring: Peter Falk, John Cassavetes, Ned Beatty, Rose Arrick, Joyce van Patten

Written by: Elaine May

Released: December 21, 1976

Length: 106 minutes

MIKEY AND NICKY is a fairly simple movie, at least on its face. John Cassavetes is Nicky, a paranoid man holed up in an apartment for reasons that are initially only alluded to, although it seems as if the recent murder of a bookie might have something to do with it. Peter Falk is Mikey, Nicky’s lifetime friend who comes to his aid (not for the first time, it turns out) and just seems exhausted. His relationship with Nicky seems to swing between that of an older brother and of a father. At the beginning of the movie, he force-feeds him medicine; near the end of it, he’s fighting him in the street.

The above premise leads us into that most satisfying of movie genres, that of the night-time odyssey through the streets of a major city, in this case, Philadelphia. Nicky, fearing for his life, wants to constantly be on the move, while Mikey seems most concerned about keeping themselves in one place for reasons that are initially ambiguous. All the while, they appear to be followed by a gangster, played by 70’s perennial Ned Beatty.

MIKEY AND NICKY presents itself as a two-character play for the most part. As they bob and weave from one place to another, we get to see a lot of conversations between our two titular characters. As a result, we gain a ton of insight, implied or otherwise, as to the relationship between the two of them, as well as their own individual lives.

And, boy, do we have two great leads to present this tandem.

I want to first dig into Cassavetes’ work as Nicky. John Cassavetes is known more as an influential independent director now that it’s all said and done, but his career started as an actor. His appearance in MIKEY AND NICKY is interesting to me since the movie itself feels so influenced by Cassavetes’ directorial work; so much of it is close, intimate and honest.

Cassavetes’ Nicky is all tics and neuroses, befitting a man who feels like every moment could be his last. He’s obviously not taking care of himself and has a penchant for rash and impulsive actions, which is why he’s found himself in trouble in the first place. He refuses to do anything to take care of the ulcer he’s obviously suffering from. And most of all, he’s unspokenly suspicious of his only friend (as it turns out, rightly). Cassavetes has a lovely, natural chemistry with Falk, no doubt the result of years of collaboration together.

Peter Falk is yet another one of those guys that I think we all know, but maybe don’t appreciate to the fullest. I’m ashamed to say it, but I’m actually not that familiar with his most famous role, that of Columbo. But I have become increasingly more acquainted with Cassavetes. But, man, is there an emotion that face, that so unique face, couldn’t so subtly register and embody? In a movie that’s all about what’s not being said (like jazz, man), Falk’s portrayal of Mikey is the audience’s emotional Cliff Notes. You are keenly aware of his overlying (and often conflicting) feelings: guilt, exhaustion, genuine brotherly affection, anxiety….it’s all there. I don’t know that the movie would have worked without him.

Both Falk and Cassavetes complement each other’s performances so well. Nicky comes off as so sufficiently tiresome that Mikey’s frustration and exhaustion with a lifetime of being maybe his only friend feels justified and obvious. His eventual betrayal also feels emotionally true, and Nicky slowly sussing out how the night is destined to end without ever truly explicitly confronting Mikey about it is ultimately where MIKEY AND NICKY derives its power.

(May I say how much I like mob movies that are almost exclusively about the lowest rungs on the org chart? So many are about making your way to the top. However, MIKEY AND NICKY there’s much drama to be wrung from the people that are frankly fortunate to even be at the bottom.)

The production of MIKEY AND NICKY was the one that appeared to run May away from the director’s chair for over a decade. Filmed in 1973, the movie wouldn’t be released until 1976, so long and how tense the conflict was between her and Paramount Pictures, her old foes from A NEW LEAF.

Again, May’s budget ballooned quickly; when the movie was being produced by Twentieth Century-Fox, the budget went from $1.6 mill to $2.2, which caused the studio to drop the film entirely, allowing Paramount to swoop in to save the day. Paramount’s involvement came with stipulations, the most vital of which were the $1.8 million budget and the hard deadline of June 1, 1974 for the film to be completed. Well, 6/1/74 came and went, and no completed movie was delivered, although the budget had inflated to almost $4.5 mill.

Part of the extended production had to do with May’s decision to constantly keep the camera rolling, maybe for hours at a time if she deemed it necessary, even when Falk and Cassavetes had long since left the scene (as the famous story goes, a new camera operator got in trouble for calling “cut”; when asked why in the world the take should continue after the actors left the physical set, May replied, “because they might come back”). As a result of this unusual decision, the film has this completely improvisational feel to it, even though it indeed was pretty much entirely scripted all the way through.

I’ve always had mixed feelings about this approach. On the one hand, it does feel wasteful, and I can’t help but understand why Paramount was having a panic attack regarding all this. I also don’t quite understand the point of continuing to roll the camera at the end of the scene if you’re following along with a tight script. Except to say that, as mentioned, MIKEY AND NICKY has this sprawling feel as a result. Even though the film is only 106 minutes, it feels, in the best way possible, like you’re with these two characters the entire twelve or so hours that the story unfolds during. You’ve been through a marathon evening, and I don’t know if the movie would have had the same effect if a more efficient director (say, Clint Eastwood) had directed it. We’ll never know.

Anyway, Paramount took Elaine May to court. Having flashbacks to how everything regarding A NEW LEAF went down, May was determined to not let the same studio butcher two of her movie. She took the extraordinary measure of essentially holding two reels of the movie hostage, storing them in a garage in Connecticut that belonged to a friend of her husband’s. She eventually relented and allowed Paramount to create the final cut, although the experience was devastating enough that she wouldn’t return to the director’s chair for another ten years.

Maybe all of this was the sacrifice needed to make MIKEY AND NICKY what it was. Because interestingly, although I ultimately don’t think it hangs together quite as well as THE HEARTBREAK KID, I think if I had to recommend just one Elaine May film, it would be this one. It illustrates so well the disruptor spirit that May retains to this day. She made a masterpiece by doing it her way, even though her way led her into a courtroom once again, and her treating a random suburban garage like it was WACO or something.

And, more importantly to me, this version of MIKEY AND NICKY ultimately led me to this moment right here, turning this space where I was awkwardly reviewing episodes of SNL or whatever to a space to talk about movies and why they work. It was a joy to run down the streets of Philadelphia again. Do yourself a favor and do the same sometime this week, too.

FOUR WEEKS OF MAY: THE HEARTBREAK KID

Men are the worst.

It’s a thought as old as the earth itself, and the reality of that statement is something that society is still currently trying to grapple with in real time (and maybe not doing such a wonderful job at it). But, look, it’s true. Certainly everyone gets anxious and insecure at some points in their lives. But there’s something about how specifically male insecurity and anxiety manifests itself that can be simultaneously interesting and infuriating. It seems like female insecurities manifest in damage done insularly, the type done to the self. Male insecurity tends to lead to outward damage, the type that’s done to other people.

Hilarious, right? We all laughing yet?

I say all this because, on rare occasion, you happen to run into a film from fifty years ago that shines a light on this concept of male insecurity so succinctly and precisely WHILE somehow managing to stay sharply, acidly funny and oddly poignant throughout its 106 minute runtime.

Naturally, it was directed by a woman.

Let’s dive into THE HEARTBREAK KID.

THE HEARTBREAK KID (1972)

Directed by: Elaine May

Written by: Neil Simon

Starring: Charles Grodin, Cybil Shepard, Jeannie Berlin, Eddie Albert

Released: December 17, 1972

Length: 106 mins

Lenny Cantrow (Grodin) and Lila Kolodny (Berlin) are a pair of newlyweds a few days into their cross-country honeymoon. Lenny isn’t feeling so great about it, now that the luster and shine of the wedding is starting to fade. He’s noticing things about Lila he didn’t before. Her sloppy way of eating egg salad, for instance. Or the way her skin easily burns in the sun. The reality of “til death do us part” is starting to hit him in his soul, and it’s starting to eat at him immensely not even a week in.

Once he runs into Kelly Corcoran (Shepard), a beautiful, young, leggy blonde, on a Florida beach, Lenny becomes bound and determined to woo her, in defiance of all logic or respect to his new bride. Kelly seems to be into him, but her father (Albert) remains completely unimpressed. THE HEARTBREAK KID becomes a long race to the altar as Lenny has to maintain his pursuit of Kelly while still keeping his honeymoon going smoothly. The script, a Neil Simon adaptation of a Bruce Jay Friedman short story, firmly establishes its main character as an unabashed skunk, a man who only decides to talk to his wife about ending things once he has no further choice, a man who weaves lies that barely make any sense and only skate by because his bride idealizes the idea of being married to him beyond all reason (in the way only the young can).

There’s no real getting around it: Lenny is a goddamn monster who’s reckless with the heart of a woman whose only definable crime is being normal. However, he’s nevertheless presented with honesty and wit. Thus, you as the audience are faced with the sudden reality of, if not actively rooting for Lenny, at least sort of hoping he gets egged on so you can watch him dig himself deeper and deeper into his scheme.

This kind of duality (serious scenes presented as comedy) is sort of typical of Neil Simon material. Take something like BAREFOOT IN THE PARK, a play about a pair of newlyweds who are essentially fighting the entire time. The thing about stuff like this is that the only way for it to work is for everybody involved in the production (actors, producers, the director, costume department, everybody) to be on the precise wavelength that the script demands AND have the ability to execute on it. In the example of BAREFOOT, if the fights are played too realistically, this comedy all of a sudden becomes an unpleasant, uncomfortable drama. Play it too over-the-top “funny”, however, and the play collapses entirely, the characters nothing more than broad and un-relatable caricatures.

So it goes with THE HEARTBREAK KID, which is threading such a small and tight needle. The entire movie hinges on Lenny being driven almost entirely by id and the need for sexual conquest and validation WHILE still staying likable to your audience (I wouldn’t be surprised if some people feel the movie doesn’t actually thread it successfully). His complete and total terror at staring down the barrel of forty or fifty years with his new bride and his weaving of his increasingly outrageous lies to her in order to keep spending time with Kelly should be funny, rather than reprehensible (which, of course, it is).

This requires absolutely nailing your choice of leading man. If he plays the nastiness too realistically, the movie becomes unwatchable. However, if the comedy is approached as too broad, the movie flatlines. Although we laugh at him, we ultimately have to believe and feel Lenny’s internal tension, or else there’s no reason for him to be doing what he’s doing. It’s a pivotal casting decision.

Enter Charles Grodin.

We’ve talked about Grodin in this space a little bit before. Specifically, I’ve previously talked about him hosting the 1978 Halloween episode of Saturday Night Live, maybe one of the greatest nights of the show ever (the whole breakdown is here, but the TL;DR version is that the whole episode hinges on a meta bit that Grodin missed dress rehearsal and now has to fumble his way through all of the night’s sketches). He also appeared in movies that have either become cult favorites (CLIFFORD) or childhood staples (BEETHOVEN). However, I’d argue he made the bulk of his career off of perfecting a “prickly asshole” persona on late night shows, sparring with Letterman and Conan for years.

Well, you could consider THE HEARTBREAK KID the starting point of that acidic persona. I legitimately don’t know who else could have done this role, either now or in 1972 (I know there’s a 2007 Farrelly Brothers remake starring Ben Stiller. I haven’t seen it; it’s possible it’s good, though I have my doubts. But I don’t think that Stiller is quite right, as funny as he often can be). Grodin just presented himself as so unassuming and normal, at least in relation to other movie stars at the time. But he also knew how to express every thought and gear turn inside his head without doing much with his face at all. This kind of thing allows him to practically get away with murder, comedically speaking. He makes breaking a woman’s heart and bringing her to tears seem like the funniest shit you’ve ever seen. That’s comedy magic, baby.

Grodin as Lenny is funny in the way that Jason Alexander was funny as George Constanza. You both simultaneously hate his guts AND eagerly await him continuing to spin plates in anticipation of everything collapsing. Actually, I thought about George and Seinfeld a lot while watching THE HEARTBREAK KID. Doesn’t the whole “I got into an accident last night” set of lies feel like a George bit? Doesn’t explaining his beach tan away by explaining he had to sit on the steps of the courthouse for hours feel like something only a Constanza could have come up with?

The supporting players are also perfectly cast. Cybill Shepard I’ve long been familiar with, and she’s someone I honestly hadn’t thought much of. But she makes for a good straight woman against Grodin’s schemer. Kelly’s role is essentially to be this perfect girl for Lenny to lust after, but I think it’s crucial that the movie presents her as a real person. She goes to a good school, she’s obviously intelligent, and her sexuality is implied rather than displayed, which prevents her from just being a sex object. This is where I think May’s touch and eye becomes so crucial; the scene where Lenny and Kelly play the “no touching” game could have easily been presented as salacious and leering in a time when mainstream movies were starting to push and experiment with how sex would be displayed on camera (same year as LAST TANGO IN PARIS!). Instead, everything is cut just so that you remember more happening than there really is.

I wasn’t familiar with Jeannie Berlin at all, to the point that I didn’t know until sitting down to write this that she is in fact Elaine May’s daughter, which clarified a lot for me. In fact, this is the only major work I’ve seen her in. She’s great! Again, Lila’s only real sin in Lenny’s eyes is just not being an unattainable supermodel. She gets bad sunburns! She’s a little messy! (One might argue that Lenny considers her too Jewish, but I am not nearly adept enough at untangling the film’s Jewish/WASP politics; the good news is that there are plenty out there who are, and you should definitely give them a read.)

Like many in this film, the role of Lila is precise and deceptively difficult. “Be normal” might be the single most difficult assignment a performer can get. You’re basically telling an actor not to act. Yes, it’s funny to see her miss a spot when she’s wiping her mouth, but the only way it remains so is if she’s nonchalant about it. Berlin understands that so well, and plays the reality of everything so honestly that it makes Grodin’s frustration during that famous dinner scene so much funnier. It’s no surprise she earned a Best Supporting nomination at that year’s Academy Awards.

Eddie Albert also snagged a Best Supporting nomination, eventually losing out to Joel Gray for CABARET (I mean, what are you gonna do?). Albert’s role is equally as non-flashy as Berlin’s, and I have to imagine the Oscar nom was built off the back of the scene at the end where Mr. Corcoran tries to buy Lenny out and make him go away (“I’m a brick wall!”). It’s a great scene, Lenny’s “final boss” of sorts, as the one guy he can’t bullshit. Albert, of course, is probably best known from GREEN ACRES and movie work like (oh hey!) ROMAN HOLIDAY. His veteran presence is wonderful here, too, as you keep waiting for him to take a swing at Grodin.

The thing about this movie, which is sort of a hard thing to admit, is that May and Simon’s analysis of the fragility of the male ego is so on point. I’d venture to guess there’s a variant out there in the multiverse of every man on the planet that approaches life the exact same way that Lenny does here. Sometimes the immediate next step of committing to a goal is dealing with the regret of having committed to it. The only real way for men to win at life is to make sure that version of him remains in the multiverse. Lenny makes it his prime timeline.

To that end, the movie surprises by not necessarily ending in a total collapse for Lenny (perhaps that’s the biggest difference between him and the George Constanza character). Actually, he more or less accomplishes his goal of winning Kelly’s hand in marriage, even resisting her father’s bribery offer. Even the presumed punchline of Lenny immediately having a panic attack about spending his life with Kelly, the allure of a lusty romance forever punctured, doesn’t quite materialize.

Instead, the dark joke of THE HEARTBREAK KID ends up being that Lenny’s success is pyhrric. Yes, he’s secured his beautiful 22-year old bride, and he’s now a part of an elevated society that would previously have been unavailable to him. But…now what? He can’t exactly BS his way through the Corcoran circle of family and friends like he could with Lila and her family. He’s not impressive in any way. Nobody except maybe Kelly really likes him.

By the end of the movie, he’s functionally completely alone, without another card to play or bullet to fire.

As far as the “Elaine” of it all, it seems by all accounts that the production of THE HEARTBREAK KID was relatively smooth sailing, at least as compared to the trouble she had with A NEW LEAF, and the all-out chaos that would ensue with MIKEY AND NICKY and ISHTAR. Maybe that’s why it feels so tight and efficient in comparison to her first film (which really only starts showing signs of meddling towards the very end anyway). There’s a clarity of thought that the movie is able to see through from start to finish. I have to wonder if this movie would have worked at all without her comedic sense at play here.

As it stands, I loved it, and it might be a new entry in my “Favorite Movies” category. For a couple of bucks on Youtube (or for free; there are a couple of champs who have uploaded it in full on that site), you can enjoy it as well.