Recent Articles

We Are The Story: Robert Altman Walks in NASHVILLE

This week, we complete our look back at Robert Altman’s work of the 1970’s with a deep dive into NASHVILLE, a sprawling panorama of the country music scene, of how we treat celebrity, of the intangible desire for change, of…well, practically everything, really.

As there must always be in every subculture across the Internet, there’s an ongoing discussion currently being held amongst the denizens of Film Twitter. This time around, it’s about the necessity of sex scenes in movies. I promise this is going somewhere.

Like many, I’ve been burned many a time by a sex scene popping up out of nowhere, usually when a parent or relative has just walked into the room (thanks, THE TERMINATOR!). And no doubt, there are many, many, many films and indeed entire genres that have sex scenes that exist only to (at best) titillate or (at worst) leer at a unsavory circumstance. However, I will mention that determining that kind of intent usually requires at least a little context, both onscreen and off, as well as some prior knowledge into the director’s prior work.

This is why a sincerely-held blanket “get rid of ‘em” philosophy gives me pause. Some are needed, some aren’t. And even if it’s not needed, I often think, who cares? Are jokes in film needed? Shouldn’t the characters stop being silly and just get to the point? But people joke in real life, so it becomes a movie thing. So it goes with sex.

As near as I can tell, a lot of the pushback on characters fucking is coming from intense old man voice Gen Z-ers on TikTok (Enjoy being blamed for everything for awhile, kiddos! We millennials had our turn). To some degree, then, this “discourse” can simply be chalked up to a lot of young people working out their feelings towards art, maybe for the first time, all against the backdrop of an increasingly complicated world. They’re just doing it on a never-ending public forum, something that a lot of us are extremely fortunate didn’t exist when we were in our teens and early twenties (a lot of my dog shit opinions are gone, nothing but so much internet dust now).

I also think the slow development over the past two decades of blockbusters becoming sexless, almost asexual, has pushed this topic to its boiling point. The FAST AND FURIOUS franchise serves as an almost too-perfect litmus test. Consider Dom and Letty, the defacto “main relationship” of the entire series (if you don’t count Tej and Roman), a couple that goes from grinding on each other in the first movie, 2001’s THE FAST AND THE FURIOUS, to barely touching by F9: THE FURIOUS SAGA. Whether this is a development of people being able to get their kicks and thrills for free from other media, or a consequence of film franchises now mostly being so many action figures being smashed together, I couldn’t quite tell you.

However (I’m arriving at “the point”!), others have identified a less obvious, but more consequential, source of sex scenes being considered by some as “unnecessary” to the plot of a given movie. It’s this: in a world where everything is “content”, anything that doesn’t move that “content” forward is thus anathema to enjoyment. In other words, the plot is now the thing. You can see this in action within, say, the MCU fan circles, where the multimedia franchise’s quickly-atrophying critical and popular acclaim over the past couple of years is getting explained away as the recent movies simply just “not moving the plot forward yet” (ignoring the fact that a few of them since AVENGERS: ENDGAME have just plain not been good movies).

This theory makes the most sense, at least to me. This mindset, if sincerely held by a significant amount of film fans (and in a world where exaggerating complaints to generate outrage, who knows if there’s truly a majority at play here), is a shame! On the one hand, yes, stories are what we ultimately go to the movies for. But stories come in so many forms, and can be told in so many different styles. A binary system of determining whether a story is “being moved forward” or not shields you from a bunch of different storytelling possibilities.

Case in point (see? “The point”! We’re here!), the story of 1975’s NASHVILLE is wide in scope and breadth, yet it’s told via tiny scenes that seems disconnected until they’re not. And often, the disconnect is sort of the point, too. Most scenes in it are explicitly not “moving the story forward” in a macro sense, yet when it’s all taken as a singular piece, not a single thread of the tapestry turns out to be out of place.

It’s an ambitious film, and one that is regularly considered Robert Altman’s magnum opus. Without having seen the entirety of his filmography, I’m still willing to go along with that, if only because of its wild confidence. There are so many characters and so many overlapping developments and movements that you’d expect it to collapse under its own weight, were it not for Altman’s light touch and almost audacious assurance.

More than anything, NASHVILLE shows that stories can be told any number of ways and be just as impactful in its totality than almost any film being made in the modern market. And that makes it worth a watch no matter who you are.

NASHVILLE (1975)

Directed by: Robert Altman

Starring: too many to count

Written by: Joan Tewkesbury

Released: June 11, 1975

Length: 160 minutes

What is NASHVILLE about? Well, there’s a short answer, and there’s a long answer.

In short, the film provides a snapshot (or maybe a panorama) of the beating heart of the titular city’s music industry, at least as it stood in the mid-seventies. A bevy of singer/songwriters and producers, some well-established, some who are aspiring, and some who have had better days, descend upon the Tennessee town in advance of an upcoming concert/fundraiser for Hal Walker, a rousing underdog Presidential candidate for the fictional Replacement Party (a candidate we hear a lot from but, tellingly, never actually see).

In long, though, it’s almost impossible to really illustrate what it’s “about” at first watch-through. The sheer scope of everything you see, of the criss-crossing storylines, of the absolute volume of characters at work here, and the way many of them disappear from the film juuuuust long enough to make you think maybe they’re not coming back, just in time for them to get a showcase scene….it’s probably best to just take it in the first time.

Oh, and NASHVILLE is also a de-facto musical, and one of significant heft. By someone else’s count, there’s about an hour’s worth of music (about a third of the film’s runtime), but it truly feels like a constant throughout. Infamously, many of the key songs (including the Oscar-winning “I’m Easy”) were written by the actors who sang them, something that apparently rubbed actual contemporary Nashville musicians the wrong way at the time. A fascinating New York Times article details the community’s reactions to the movie’s premiere in the real-life Nashville. There weren’t any riots or anything, but honest-to-god country superstars like Loretta Lynn seemed a little riled that actual country music artists weren’t used to develop the music.

Most of the time, I’d be on their side; a lot of the creative work (and the expertise to be found among it) has slowly been slid onto the plate of the onscreen performer, to the point that it seems most people assume everything is now improvised on set (seriously, fire up an episode of the OFFICE LADIES podcast sometime; 85% of the questions they get are some variation of “was [insert line or moment] improvised????”)

But, here’s the thing. I actually didn’t know the actors mostly wrote the music going in, and was a little shocked to learn it as a fact. It just all sounded like mostly legitimate country and bluegrass to my untrained ear. So, my sincere props, y’all! The New York Times article talks about how many of the lyrics were met by the country insiders in the audience with smirking recognition, perhaps indicating a level of parody at play here that mostly flew over my head. I just thought the music was actually good!

Another reason country stars, and thus Nashville proper, didn’t warm up to the film right away was this uneasy sense that they were being made fun of. After all, what is there to make of these exaggerated characters representing your home turf? Rumors also swirled that some of the major characters were one-to-one stand-ins for major current country stars which is, uhhhh somewhat true, actually; for instance, Barbara Jean is based on the aforementioned Lynn, Tom Frank (Keith Carradine) is based on Kris Kristofferson. Some characters were merely composites; Connie White (Karen Black) is a mix of Tammy Wynette, Dolly Parton and Lynn Anderson, while Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson) is a cross between Porter Wagoner, Roy Acuff and Hank Snow.

Naturally, Altman had always resisted this literal interpretation. To hear it from him, NASHVILLE is, if anything, a movie about Hollywood. This narrative framework was just set in Nashville mainly because of his growing affinity for the area. Although the film was mostly improvised on set, the standard modus operandi for Altman by this point, Joan Tewkesbury had provided the road map, filling up a diary of her notes, experiences and observations. Some of them made it directly from her pages to his film, most notably the freeway pile-up that begins crashing the characters together.

But the actual tapestry of NASHVILLE? The ecosystem of country music and the eccentrics that it attracts, all amidst this feeling of unseen, intangible hope, could just as easily be applied to the film scene in California. Or the theater scene in New York. Or a million other subcultures in this strange, bizarre, wonderful world we live in. Anyone who’s found a community through passion can recognize the archetypes at play; the fallen star, the up-and-comer, the knowing cad, the overzealous fan, the service man who wants to climb the ladder.

More to the point, NASHVILLE is so clearly about the American experience, both in broad and specific terms. It is both intensely of its time, yet unbelievably timeless. Hell, many of the key creatives behind this might be shocked (or appalled) at how relevant it all still is.

NASHVILLE is very much captured in 1975, in particular when considering how much shit had gone down in America the previous fifteen or so years. JFK, MLK, Malcolm X and RFK’s assassinations had all been in the past twelve years (something that is so clearly on this movie’s mind; more on that in a second), and the Watergate scandal earlier in the 70’s had done much to erode what was left of the population’s confidence in its government after the prolonged war in Vietnam.

A strong desire for change was in the air, although if NASHVILLE is to be taken at face value, there was skepticism that it was really going to be possible, at least not without a fight. As mentioned, Hal Walker, the reason the story of the movie is even happening, the speaker of many amazing and rousing platitudes….dramatically speaking, he’s a ghost. We never see him, his words just sort of float through the atmosphere. Everyone gathers for the mere possibility of change, even if we don’t know what it looks like.

A lot of NASHVILLE’s thesis statement can be gleaned from its pretty glorious opening scene, two songs being sung in completely different styles, recorded in completely different contexts, and sung by people of completely different races. One half of the scene is Hamilton attempting to record a very straight-laced and traditional Bicentennial song, a literally-titled “200 Years” (written by Hamlin and Richard Baskin). Its chorus refrains, proudly if a little naively “we must be doing something right to last 200 years!” It’s rousing, if staid to its core.

The other half, in another room within the same recording studio, is Linnea Reese (Lily Tomlin) and the all-black Jubilee Singers (from Fisk University, at the very least based off a very real choral group, although I couldn’t confirm if they were appearing as themselves here) laying down a rousing gospel track. As the piano joyously pounds, Linnea struggles to be heard over the voluminous sound behind her, asking over and over if we believe in Jesus.

Two completely different and unique styles, borne from diametrically opposed lived experiences and perspectives, living right next door to each other. That’s Nashville. That’s America.

******

It’s difficult to figure out exactly who to best highlight amongst NASHVILLE’s cast. There are so many moving pieces within its ensemble cast that you could probably watch the movie ten times and have a new favorite every single time. However, I’ll highlight a couple that took me by surprise.

Like many comedians from the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, I was primarily familiar with Lily Tomlin from her hosting stints on Saturday Night Live, although most people at the time probably knew her from ROWAN AND MARTIN’S LAUGH-IN. Folks nowadays likely know her from stuff like GRACE AND FRANKIE, a comedienne from previous generations that thankfully appears to be accepted and loved by younger generations (also known as the Catherine O’Hara Club). I hadn’t really ever seen her do a non-comedic role, however, although I had little doubt she’d be great.

She comes through! I think what really surprised me and made her stand out is that Linnea is so normal compared to both everyone else in the dang movie as well as every other character I’ve seen Tomlin play. She’s heartbreaking in her simplicity and nobility, a gospel singer that takes care of her two blind daughters, all the while being left unsatisfied by her husband (more on him in a second!). When she gets the chance to sleep with Tom, she can’t resist.

Linnea could be a really difficult character to sell to an audience, but Altman or somebody must have known that we were going to love her because she’s Lily Tomlin. They were right. One of the most unforgettable and memorable moments of NASHVILLE’s entire 160 minutes is her staring silently at Tom singing her “I’m Easy”. Maybe she knows she’s making a mistake, maybe not. All she knows is she’s doing something for her. She does all of us without a single written line of dialogue. I’m convinced she’s why the song won an Oscar.

If there’s a main backbone to the film, it’s probably the story of Barbara Jean’s recovery from a nervous breakdown. Ronee Blakely plays half of her scenes laid up in a wheelchair, but I found her entire arc pretty engaging, if only because it reminded me so much of how celebrities, especially women, tend to get squeezed from all ends until they collapse, sometimes emotionally and sometimes literally. Every aspect of her arc here happens publicly; her return, her collapse, her heartbreaking failed performance at Opryland (a scene so beautifully acted by Blakely, by the way, that I felt like I was watching a concert doc, not a narrative film), her violent death.

About the only thing she gets to do in private is recuperate. Even then, she gets to watch from her wheelchair as more glamorous performers take her now vacant slots, and she gets to observe her well-meaning manager/husband Barnett dismiss her anxieties as the beginnings of another nervous break. She never catches a break once in the film, but that’s how it goes for female celebrities throughout the past, present and future. We feel for them only when they’re finally at rest.

Barbara Baxley, star of both stage and screen, provided one of the other most memorable moments of the movie for me as Lady Pearl, the wife of Haven Hamilton. Midway through NASHVILLE, she gives this speech to Opal, a British reporter and our de-facto audience surrogate. Within this monologue, she talks about the reach John F. Kennedy Jr. had on areas of the country not previously thought possible, his subsequent assassination and. In doing so, she verbalizes and dramatizes the deep national tension at the time (and was still very much lingering in 1975) that NASHVILLE taps into so well:

And then comes Bobby. Oh, I worked for him […] he was a beautiful man. He was not much like John, you know. He was more puny-like. But all the time I was workin' for him, I was just so scared - inside, you know, just scared.

It’s here that the film starts to contextualize its ending. More on that in a second.

Finally, was there some sort of presidential order signed that mandated Ned Beatty appear in every single great American 70’s movie? This marks his third appearance on this blog in just under a year (including NETWORK and MIKEY AND NICKY). And, no surprise, he’s fucking great. You’re never going to believe it, but he plays an unsavory lush in this, although it’s notable that he never really does anything unsavory. He’s just not there for this saint of a woman he’s lucky enough to share a roof with. I’m a little shocked that Beatty only worked with Altman one more time (1999’s COOKIE’S FORTUNE). He’s a natural for the expository nature of his film set.

I could go on and on and on about every single character, and a real legitimate breakdown of this movie would almost have to in order to really dive into every nuance. You’d have to because these characters are the story. They are the plot, and the plot is them. Their human decisions affect the decisions of others. Or they don’t. Maybe their stories are purely internal. But that’s the story of humanity.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t talk about the ending, and why it’s so powerful in the midst of a world where just stepping outside can feel fraught with peril, where scanning the news invites you into a nightmarish hall of mirrors. In NASHVILLE’s final scene, as we finally reach the Hal Walker fundraiser, Barbara Jean gets assassinated on stage by a quiet, seething fan (a moment that seems eerily prophetic in the aftermath of Christina Grimmie’s 2017 murder, resulting in a world where stars like Taylor Swift have to walk around with what is essentially human Fix-a-Flat), and her limp body is immediately (albeit slowly) taken off the stage.

Amidst the shock, however, the indomitable human spirit endures. A new star takes the stage, and Hamilton urges the crowd to not give up, chillingly stating “we’re not Dallas!”. The entire crowd takes up in song.

It’s both ghoulish, bizarre yet simply moving. It’s America.

Although there is an uncharitable interpretation to be made of these final moments (a prediction of our current “the show must go on” culture that has essentially rotted our brains), I took it as perversely positive. For everything that this fucking country has had happen to it (and, of course, what it’s unleashed on others, both within and beyond its borders), we have a knack for moving forward anyway. Concerts endure. Sporting events endure. Beyond all reason, we still find political candidates to rally behind. We just kind of keep going.

Just, you know, try not to get too much blood on you while you do it.

*******

Not that it ultimately really matters, but Altman seemed to find his juice at the Academy Awards again after the success of M*A*S*H had thus far eluded him in the early to mid 70’s. NASHVILLE was nominated for five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. It lost both of those, although it must be said that this particular Oscar race was incredibly stacked. Its competition for Best Picture:

ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST (eventually won)

BARRY LYNDON

JAWS

DOG DAY AFTERNOON

Altman’s competition for Best Director:

Milos Forman (CUCKOO’S NEST, and eventual winner)

Federico Fellini (AMARCORD)

Stanley Kubrick (BARRY LYNDON)

Sidney Lumet (DOG DAY AFTERNOON)

What are ya gonna do? Altman had to settle for it being considered his magnum opus almost immediately, and probably his most enduring and popular film, besides maybe something like the aforementioned M*A*S*H*. Oh, and it still holds the record for most Golden Globe nominations for a single film, even all these years later. Not bad!

This brings me back to the “discourse” at the beginning of this article. By the same metric of “not ostensibly plot related = wasted calories” that leads to the very existence of sex scenes being questioned, NASHVILLE fails any possible equation you could run it through. Yet, do you want to live in a world where a movie like it could possibly be considered bad storytelling by any measurement?

Almost fifty years later, NASHVILLE remains an astounding achievement, both in scope and scale. It manages to reflect how stories can come from anywhere and everywhere. They surround us, both small and large. They are us. And there’s no “right way” to tell them. Let movies indulge! Let them take their time! Let them take you down oddball paths! The best ones have a way of enduring even when they’re weird.

That’s America.

3 WOMEN, 1 BLOG: Altman Goes To Dreamland

This week, Robert Altman delves deep into the world of dream theory with his 1977 impressionist masterpiece 3 WOMEN. To call it a “stolen identity” movie would be to sell it far short, but maybe it’s best to just experience it for yourself if you haven’t already!

As a general rule, I like to go into the movies I review in this space as cold as I possibly can. I try not to look up analyses or reviews ahead of time, and I definitely don’t peruse any plot details. Sometimes it’s just not possible with something that has completely permeated popular culture to the point that references are simply unavoidable (say, something like GOODFELLAS or A CLOCKWORK ORANGE). Sometimes, it just doesn’t matter; what difference does the element of surprise make when you’re breaking down fucking JAWS 3-D? But in general, I only allow myself basic story setups and cast lists for review. This theoretically gives me two advantages:

1) the movie is given the opportunity to unroll on its own terms, without any sort of behind-the-scenes drama or famous inspirations behind it attempting to inform me what it should be;

2) it gives me the chance to experience movies that have been around for twenty, thirty, almost fifty years in the way that audiences at the time might have. I want it to feel like picking up a newspaper, browsing the entertainment section for showtimes (yes, this used to exist) and exclaiming “Hey, it’s a new Altman! I like him! Let’s check it out” before heading down to the theater and just….seeing what happens.

Well, this week, this process really put me in a pickle. 3 WOMEN got on my radar essentially off of a recommendation (thanks, Tony!). I had vaguely heard of it, I was aware of who starred in it. But that’s it. So far, Advantage #2 was coming through in spades.

However, as you probably are already aware, Altman’s 1977 impressionist classic is not an easy movie to just go ahead and unpack the first time around, unless you happen to have a degree from Johns Hopkins or something. Let me tell you, living in a time where every other film is booked as having “psychological thriller” elements, 3 WOMEN is one of the true “psychological” films I really can think of.

More to the point, it really, really is a film where some prior research into Altman’s intent and inspiration would have been handy. Because it’s palpably different from Altman’s most famous works, so unbelievably so that, even as I struggled to grapple with the film in the days after watching it, the thought crossed my mind that Altman might really be the best American director of his generation, so deep is his versatility.

For anybody hoping to see a man stumble through a psych class term paper, you’ve come to the right place. 3 WOMEN!

3 WOMEN (1977)

Starring: Sissy Spacek, Shelly Duvall, Janice Rule

Directed by: Robert Altman

Written by: Altman

Released: April 3, 1977

Length: 124 minutes

The story: timid and wide-eyed Pinky Rose (Spacek) starts her first day at a geriatric “health spa” located in a middle-of-nowhere California dust bowl town and immediately becomes infatuated with her gabby, effortlessly cool coworker Millie Lammoreaux (Duvall). When Millie’s roommate moves out of their room at the Purple Sage Apartments, Pinky immediately snags the opening. The two spend their time hanging out at the Dodge City saloon, owned by ex-stunt double Edgar Hart (Robert Fortier) and his mute painter wife Willie (Rule). As Pinky’s infatuation grows, her personality begins to resemble that of Millie’s. Subsequently, Millie seems to regress the further the film goes on.

The movie obviously goes on from there, but to continue would technically be to….well, not ruin the movie entirely (it’s not a film that can really be ruined by reading the plot synopsis); it’s just…well, it’s hard to describe in words exactly what the movie is fully about. Put it this way: it’s one thing to read the story of 3 WOMEN, it’s quite another to experience it. It’s both loosely plotted and intensely fixated on character dynamics, both subtle and quite bold, at once emotional and cerebral.

3 WOMEN is surreal in the sense that every moment feels both disconnected from the ones before and after it, yet it all feels completely intertwined as a piece. In that sense, the filmography that came to mind while watching this was David Lynch’s, and I became convinced 3 WOMEN was a major influence on the future TWIN PEAKS creator’s work. However, I really couldn’t find any evidence to corroborate that, and I was reminded that Lynch is sort of infamous for not watching that many other movies, so who knows.

Still, it’s hard not think about MULHOLLAND DRIVE, a movie with very similar themes and a somewhat analogous setup (two women meet by chance, and find their identities becoming intertwined), as well as a movie that saw Lynch go up directly against Altman’s GOSFORD PARK in the 2001 Best Director Oscar race (they would both lose to Ron Howard for A BEAUTIFUL MIND. Hollywood!). I’m also aware that there are strong comparisons to be made to Bergman’s PERSONA (in fact, it was a direct influence for Altman), and I feel caught a little flat-footed that I haven’t seen it. Another argument for my ongoing film literacy!

To that end, something else that made 3 WOMEN such a difficult movie for me to go into cold was that my still only cursory knowledge of Altman’s major works did nothing to prepare myself for it. There’s nothing in M*A*S*H, MCCABE AND MRS. MILLER, CALIFORNIA SPLIT or THE LONG GOODBYE to indicate the man was capable of something so impressionistic (although subsequent research suggests something like BREWSTER MCCLOUD might have clued me in; can anybody confirm?). Sure, it’s rooted in that improvisational looseness that had long since become Altman’s trademark (more on that in a second), and his impeccable knack for casting actors who would wind up legends of their time is on full display. But it’s such a departure of what I’ve seen so far, it kind of threw me for a loop.

If you haven’t caught on yet, I feel completely unequipped to really unpack 3 WOMEN, at least not on just one watch. The first screening seems to be meant solely to just take it all in. It feels like it practically demands at least a couple of subsequent re-viewings to start taking in details and themes. For instance, I definitely know what feelings Pinky’s bad dream and the pool murals evoked in me (in both cases, an intense dissettlement); I just couldn’t tell you what they precisely mean.

To be clear, this isn’t the same thing as the complaint I levied against Kubrick’s THE SHINING, which I’ve always found so vague in intent as to be almost meaningless (an opinion that I sense I am increasingly alone in holding). No, here Altman is being very specific, I’m just missing what some of the details are supposed to indicate. In this case, Bobby, it’s me, not you.

For what it’s worth, Altman has claimed the inspiration for 3 WOMEN came to him in his sleep in the form of an anxiety dream that developed while his wife was laid up in the hospital. Specifically, he dreamt that he was shooting a movie about stolen identities in the desert that starred…Shelly Duvall and Sissy Spacek. He woke up in the middle of his dream, started writing notes down on a pad, then went back to his strangely prophetic dreamscape.

Post-dream, Altman collaborated with screenwriter Patricia Resnick (who would go on to work on, among other things, 9 TO 5 and the final season of Mad Men) to develop a treatment for this project, which wound up being about fifty pages. Resnick, by the way, would go on to collaborate with Altman many times after this, starting with 1978’s A WEDDING. That screenplay was largely skirted in favor of in-the-moment improvisations, allowing Duvall in particular to have a lot of agency in developing Millie’s character on the set. his was just as well: Altman didn’t intend to really have a screenplay at all, which tracks with what the movie truly felt like, and what made it sing.

Because 3 WOMEN isn’t so much a movie about words as it is about characters, behavior and images. The power of the film comes down to establishing firmly and quickly the differences between Pinky and Millie, then slowly watching as their personalities begin to intertwine, then shift back. Right off the bat, we can palpably feel the differences between our two leads. Where Millie is chatty and outgoing (even as, it turns out, she isn’t as beloved by her peers as she wants to believe), Pinky is intense, eager and interior. Much of the power of the film is seeing the two change as they continue to interact, almost as if they’re being brought together by some cosmic (or dream) force.

What might stand out amidst all of the above is that, hmmmm, I only really count two women there. Well, the third woman is the aforementioned mute wife Willie, and it’s here that I admit to being a little stymied. Her big contribution to the film are the creation of the aforementioned murals at the bottom of the pool at Dodge City. Plot-wise, she suffers a stillborn birth and is probably complicit with the other two women in the murder of Edgar.

So, yeah, someone smarter than me may need to jump in here and give a dissertation on Willie. If I had to make a guess (and since you’ve been nice enough to read this, I think I at least owe you a blind stab), I’ve taken Willie’s stillness, in every unfortunate sense of the word, to be the sort of axis against which Willie and Pinky shift up, then down again, throughout the course of the film. I also feel like it isn’t coincidence that all three women essentially have the same name; Millie and Willie are separated by just one letter that are basically identical. As well, it’s revealed that Pinky’s birth name is Mildred, or Millie.

Now, there are much, much, much deeper analyses of 3 WOMEN out there that views the movie through the prism of dream theory, and the way that people in a dream are able to kind of shift characters within that dreamscape. To that end, the common interpretation is that the three women represent the shifting psyche, personalities and lifetimes within one woman (the infatuated child, the liberated young woman, and the older mother). It all sounds right to me, although I certainly don’t have the credentials to really dig into any that.

But, the thing is, even if you didn’t give a whiff about any of the psychoanalysis of it all, the damn thing works kinda just on the surface level of “creepy roommate” movie. Spacek plays her wide-eyed obsession so well! It’s certainly not necessarily a subtle performance (you know almost immediately there’s something off about her), but it’s also not overplayed, a mighty difficult balance to strike. Spacek is a performer that I actually haven’t seen in as many things as I had thought, yet her biggest hits loom so large that it feels like I’ve grown up with her anyway. Here, Spacek plays Pinky’s obsession straight instead of going for overtly creepy. She also plays Pinky’s lack of clear identity perfectly. You even feel a twinge of weird sympathy for her as she appears to freak out on the couple that claim to be her parents after her suicide attempt (the movie takes turns).

I’ve alluded in the past to how I’m mostly on the outside looking in in regards to the allure that Shelly Duvall has held on people over the last few generations. I’m not a hater or anything, I’ve just observed that people genuinely adore her to a somewhat intense degree. I don’t know if it’s just that I never grew up with Faerie Tale Theatre as a kid (I am making an assumption this is where most people were introduced to her), paired with the aforementioned lack of strong affinity for THE SHINING. That all said, 3 WOMEN is easily the most I’ve ever liked her. Crucially, you buy her playing “both personalities”, as Millie and Pinky start to swap dispositions and demeanors. She actually might be the biggest reason why the movie works as well as it does.

As for that third woman, crazy thing about Janice Rule: a few years before this movie’s release, the already wildly accomplished actress started studying psychoanalysis, using her fellow acting colleagues as her patients in 1973 (a veritable cornucopia of research opportunities there). She eventually earned her PhD in 1983, and practiced all the way to her death in 2003.

Two other things I wanted to mention: outside of a brief detour into the lyrical content of “Suicide is Painless”, I haven’t talked much about the scores of the Altman movies I’ve already reviewed (an especially egregious error when considered how important the different version of the title tunes are to THE LONG GOODBYE). Something in the opening seconds of 3 WOMEN that struck me immediately, however, was the dichotomy between the setting of the opening scene and the music that accompanies it.

Visually, we are plunged into a senior rehab facility (or “nursing home”, if you want to get pejorative), and it’s the type of facility you’d expect it to look like. It’s sterile, and moderately depressing, but otherwise non-descript. Yet, the Gerald Busby-composed music is quietly tense and sinister, almost like a warning. It sets up how the whole movie feels at times; everything seems recognizable, but you just keep waiting for it all to take a turn (and boy, does it ever).

One last little thing I loved about 3 WOMEN: it is a superb 70’s food movie. Tuna melts, pigs in a blanket, chocolate pudding tarts, something called “penthouse chicken”….although we don’t see much of these 70’s dinner party staples (well, except the tuna melts), the mere threat of them permeates seemingly the entire runtime. Whether this is all part of the dreamscape, or just a quirky little happenstance, it greatly delighted me. I would attend your dinner party, Millie!

In the end, film is a visual medium. More to the point, it’s an art form meant to use images as a vessel for emotion. Thus, even without a PHD in psychology in hand, 3 WOMEN was still able to make me feel strong emotions, even if they were sometimes clouded in confusion. It’s certainly unlike quite anything I’ve seen up to this point, and is possibly the movie that has screamed “revisit me!” the loudest.

M*A*S*H is Still a Banger

This week, we revisit one of the most acidic war satires in hollywood history, the original film version of M*A*S*H! While some parts have aged quite poorly, in an age of toothlessness, much of Altman’s breakout feature hits even harder now than it did in 1970.

Some movies get burrowed into your brain at such a young age that you’re no longer able to truly view it with fresh eyes, so ubiquitous is its presence in your soul during your formative years. Amazingly, Robert Altman’s 1970 breakthrough feature is one of those for me.

With hindsight, M*A*S*H seems like a very odd choice for one of those things, doesn’t it? This hyper-specific, context-demanding, ultra-black comedy about the Korean War (that’s really about the Vietnam War)? First-class entertainment for a middle-schooler in the early 2000’s.

Well, I have my mother to thank for that. Genuinely.

My mom, a woman who made the decision to flip her career, go back to school and ultimately enter healthcare at more or less the same age I am now, has had a lifelong knack for zeroing in on media set in hospitals of all kinds. Well before he became a fame-chasing hack, she was aware of Dr. Oz back when he was a world-class heart surgeon thanks to a book she owned that incidentally featured him. I recall a DR. KILDARE movie sitting on the shelf. Her favorite television programs of all time include China Beach, ER, and M*A*S*H, both the television program and the movie that spawned it.

As I recall, she had tracked the movie down on VHS sometime in the late-90’s, during a time when video cassettes were starting to wind down as the dominant form of physical media. A couple of years later, M*A*S*H was finally released on DVD, chock full of special features and director’s commentaries and it was game on from there. And she watched it quite a bit. And when you’re a kid…well, you kind of just absorb what’s on the screen.

As a result, M*A*S*H has taken on a life of its own inside my head, even after not having gone near it in probably ten years. Just to give you one specific example, I’ve been doing Donald Sutherland’s little three-toned whistle to myself for decades, usually without even realizing I’m doing it. For another example, I realized on this most recent re-watch that I still have a clear memory of every single song that plays over the P.A. system (“Tokyo shoe shine boy….”).

I was surprised how much of it I had held onto after all this time, although it won’t be a shock that the movie made much more of an impact on me now that I’m fully an adult. Though even at the time, I had a strong sense that this was different than a lot of films I had seen, as it turns out, a cynical condemnation of the Vietnam War isn’t something a twelve-year-old can fully appreciate.

But I can now. Although more than a few of its elements are rough around the edges fifty years later, the audacity of Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H still shines through. In fact, considering how toothless current Hollywood satire can be, much of it has aged even better.

M*A*S*H (1970)

Starring: Donald Sutherland, Elliot Gould, Tom Skerritt, Robert Duvall, Sally Kellerman

Directed by: Robert Altman

Written by: Ring Lardner Jr.

Length: 116 minutes

Released: January 25, 1970

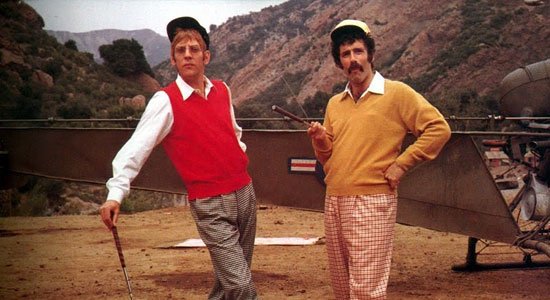

One doesn’t summarize M*A*S*H so much as just provide its basic outline: Surgeons Hawkeye Pierce (Sutherland) and “Duke” Forrest (Skerritt) arrives in South Korea and drive to the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital via stolen military jeep. As they make it to their new station, we are introduced to many of the other people already stationed there: commanding officer Henry Blake (Roger Bowen) and his assistant “Radar” O’Reilly (Gary Burghoff!), dentist Walter “The Painless Pole” Waldowski (John Shuck), man of the cloth Father Mulcahy (a very young Rene Auberjonois) and antagonistic fellow surgeon Frank Burns (Duvall), to name just a few. Two crucial late arrivals include colorful chest cracker “Trapper John” (Gould) and new head nurse Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan (Kellerman).

What happens in M*A*S*H? Well, the real answer is that, against this backdrop, Pierce, Duke and Trapper John mostly just kind of fuck around. They, like many men who got roped into an overseas war with a nebulous and unclear purpose, they spend their down time in Korea pulling pranks, harassing and sleeping with the few women there (including Jo Ann Pflug), and just…I dunno, playing golf?

That’s during downtime. When, it’s…uh…uptime, wounded and dying soldiers are brought in from the battlefield via helicopter and it’s time to get to work. Intercut through all the buffoonery are tactful-but-bloody scenes in the actual surgery room (or tent), where our characters now have to rely on their extensive training to make split-second decisions in order to patch up our armed forces.

Anarchy is the name of the game for M*A*S*H, both in terms of the characters’ attitudes to the cold chaos and injustice surrounding them, and in terms of how the film is structured. It isn’t traditionally plotted, with an A-B-C format. Instead, it kind of lopes along, moving from vignette to vignette until it abruptly concludes. This refusal of traditional format subsequently makes it a difficult movie to peg down completely.

It’s tempting to categorize M*A*S*H as a war movie or, perhaps more accurately, an anti-war movie. And this isn’t wrong. M*A*S*H is anti-war in the sense that the movie is more or less physically absent of war, as least as it’s usually presented in a Hollywood “war” film. None of our primary characters see combat, and they’re not really soldiers in the traditional sense. There is a major battle sequence to wrap up the film: a climactic football game shot like a war zone, complete with men getting hurt and collapsing to the ground.

However, bloody conflict is felt in other ways. As mentioned above, the members of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital are ultimately left responsible for the consequences of combat, saddled with the job of closing up the holes blown into the chests of men in a war being fought right in their backyards.

So, yes, it is anti-war, just not in the way we’re accustomed to. Compare M*A*S*H to something like Stanley Kubrick’s PATHS OF GLORY, an absolutely brilliant anti-war film where the injustice of war and how soldiers are expected to act against their own innate humanity is laid bare. However, we also know where Kubrick stands in regards to its message. To be infuriated, left with feelings of helplessness and desperation as these young men are led to their deaths at the hands of their own country for the crime of being scared…this is how Kubrick screams into the void. Through stark photography. Through Kirk Douglas’ masterful and steady performance.

But, M*A*S*H….doesn’t really leave you with any of that. Nobody gives a rousing monologue (in order to do that, they’d have to stop worrying if their erectile dysfunction makes them gay first), nobody verbally expresses their frustration or anxieties, nobody gnashes their teeth at their evil generals. The closest we get to something like that is the sequence in Japan, where they blackmail an annoying hospital commander by staging photos of him in bed with a hooker.

Otherwise, all of that interiority is expressed by the fucking around, the pranking, the harassment. For as strong leaders as Duke, Trapper and Hawkeye are when shit starts going down, they don’t really conduct themselves as noble defenders of liberty. In one of the biggest signs that opinion on American interventionism had taken a turn, their behavior is more akin to that of rowdy frat boys.

In this sense, maybe it’s best to describe MASH as an anti-Hollywood war film. Compared to more rah-rah films of the time (such as the movie that eventually beat it out for Best Picture, PATTON), Altman’s M*A*S*H may as well have been transported from a different planet. It’s an intentional, full-throated attack on what had come before; it’s no accident that many of the P.A. announcements throughout the film are advertisements for similar war films from around the time of the Korean War, their summaries and casts read with the same kind of nervous deadpan as one would when announcing the opening of a new latrine.

Now, given the description of individual scenes and moments above, it won’t shock you to hear that not everything about M*A*S*H has aged perfectly. It’s pretty blunt about gender and ethnic relations, the kind of movie whose soundtrack indicates the scene has changed to Japan by the banging of a gong. One of the only black characters with lines carries the nickname “Spearchucker”, with no apparent intended irony (in-universe, it’s because he used to throw javelins in high school, but come on). Strong women exist to be taken down a peg, to take the stick out of their ass.

Again, when put in context, the brazenness is the point and, to be honest, one of the most realistic things about M*A*S*H. Given the absence of anything else to do except patch up pawns in a pointless war, our characters blow off steam by being assholes. Funny assholes, but assholes nonetheless. Intense as it may be, it shouldn’t surprise you to learn that many related to this disillusionment in 1970 America.

Still, not all of it is handled with perfect grace. Maybe its most disappointing failure is in the depiction of Hot Lips Houlihan. Maybe the confusion as to the goal of this character as writ is aggravated by the fact that she’s played by Sally Kellerman, someone I’ve always found a little annoying (fire up a couple of her musical numbers from LOST HORIZON sometime if you disagree), putting her at a disadvantage in my heart and mind. But I think M*A*S*H the film fails her in the end.

It’s not so much that the horned-up, frustrated men surrounding her decide to take her down a peg simply for the crime of being a strong-willed woman in a war zone (again, this mostly reads as sadly realistic); it’s the fact that she becomes dumber and dumber as the movie goes on. During the infamous “shower scene” (where the curtains get pulled down, revealing her in her entirety to the entire squad) and her subsequent explosion at Blake, we both feel her exasperation, her frustration at the insanity that surrounds her (and we darkly laugh at Blake barely giving a shit, such is the male military machine).

From there? We never see that strong “head nurse” character again. By the time we get to that climactic football sequence, she’s a “blithering idiot” head cheerleader. Now, writing this all out, this sounds like an intentional shift, a consequence of being worn down by the hyper-masculine gears of war. But if that’s the case (and it may be!), it needed to be more apparent, at least for me. As it stands, her enthusiastically misunderstanding even the basic fundamentals of football as a sport feels like it’s meant to be genuinely funny. This may be a misread on my part.

Thankfully, the movie is bursting at the seams with iconic performances regardless. Donald Sutherland’s turn as Hawkeye has gotten swallowed up whole when Alan Alda’s version became essentially the only one in the public consciousness now. But he’s terrific here, playing him as a laid back observer of humanity. Once again, young Elliot Gould was a force to be reckoned with, and it’s no accident that the movie goes into another gear once Trapper John enters the fray. He’s anarchy personified, and he’s perfect.

As for Tom Skerritt, did anybody have a better knack for being in the most popular movies of all time? This, ALIEN, TOP GUN, STEEL MAGNOLIAS….though Duke may be the lesser of the three leads (and the only one not to be carried over to the TV show), he brings a nice cool-guy energy to perfectly balance out Sutherland and Gould.

Whether M*A*S*H is Altman’s best work is highly debatable. However, it might be the most indicative of his directorial trademarks, and a good early rubric for what to expect from his films going forward. All of that iconic overlapping, improvisational speech is in full force here, and it’s hard to imagine the film being any other way. What better way to effectively communicate the chaos under a MASH unit tent than everybody talking over each other?

(It should be noted the overlapping speech is also used for comedic effect, usually through Gary Burghoff’s Radar, who remains a half-second ahead of Major Burns’ orders.)

Of course, maybe the biggest ding to M*A*S*H ‘s legacy is the subsequent legacy of its spinoff project….uh… M*A*S*H, the CBS sitcom that ran for eleven years and cranked out a finale that to this day remains the single most watched episode of television in American history. For as much of a smash as MASH was in 1970, by the 80’s, the definitive versions of these characters had been cemented into the country’s consciousness.

I will say that the basic idea of M*A*S*H actually translates pretty well to episodic television (the movie is more or less structured like a bunch of episodes smashed together), but it’s always amused me how much Robert Altman hated and resented the TV show. He admitted as much in an out-of-nowhere moment on, of all things, a DVD commentary track. Whether or not he’s off-base, I’ll leave up to you. However, I always respect people who wake up extra early to be the best hater they can be.

Okay, one other thought re: the television series. We all know its theme, that somewhere-between-jaunty-and-somber instrumental melody line to “Suicide is Painless”. It’s classic, maybe the single most recognizable sitcom theme of its day. Re-watching the movie, however, made me remember that we get the full song and lyrics not once, but TWICE (once during the opening credits, and one at Painless’ “funeral”). And, folks, I was reminded that “Suicide is Painless” is one of the most nihilistic songs ever written.

The game of life is hard to play

I'm gonna lose it anyway

The losing card I'll someday lay

So this is all I have to saySuicide is painless

It brings on many changes

And I can take or leave it

If I pleaseThe sword of time will pierce our skins

It doesn't hurt when it begins

But as it works its way on in

The pain grows stronger, watch it grin

Woof. It’s very funny to me that this has managed to become a thirty-second jingle that everyone instantly recognizes from reruns. There’s a reason they left the lyrics off the opening TV credits.

All in all, M *A*S*H’s legacy was immediately secured, earning five Academy Award nominations, although it won only Best Adapted Screenplay. Fifty years on, I think it deserves more shine than it does now, eclipsed by a long-running sitcom and later, better work from its director. It’s an American satire so anarchic that it seems almost unbelievable it got made at the time, much less now.

Isn’t that worth a look?

Best of

Top Bags of 2019

This is a brief description of your featured post.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sign up with your email address to receive news and updates.