Recent Articles

M*A*S*H is Still a Banger

This week, we revisit one of the most acidic war satires in hollywood history, the original film version of M*A*S*H! While some parts have aged quite poorly, in an age of toothlessness, much of Altman’s breakout feature hits even harder now than it did in 1970.

Some movies get burrowed into your brain at such a young age that you’re no longer able to truly view it with fresh eyes, so ubiquitous is its presence in your soul during your formative years. Amazingly, Robert Altman’s 1970 breakthrough feature is one of those for me.

With hindsight, M*A*S*H seems like a very odd choice for one of those things, doesn’t it? This hyper-specific, context-demanding, ultra-black comedy about the Korean War (that’s really about the Vietnam War)? First-class entertainment for a middle-schooler in the early 2000’s.

Well, I have my mother to thank for that. Genuinely.

My mom, a woman who made the decision to flip her career, go back to school and ultimately enter healthcare at more or less the same age I am now, has had a lifelong knack for zeroing in on media set in hospitals of all kinds. Well before he became a fame-chasing hack, she was aware of Dr. Oz back when he was a world-class heart surgeon thanks to a book she owned that incidentally featured him. I recall a DR. KILDARE movie sitting on the shelf. Her favorite television programs of all time include China Beach, ER, and M*A*S*H, both the television program and the movie that spawned it.

As I recall, she had tracked the movie down on VHS sometime in the late-90’s, during a time when video cassettes were starting to wind down as the dominant form of physical media. A couple of years later, M*A*S*H was finally released on DVD, chock full of special features and director’s commentaries and it was game on from there. And she watched it quite a bit. And when you’re a kid…well, you kind of just absorb what’s on the screen.

As a result, M*A*S*H has taken on a life of its own inside my head, even after not having gone near it in probably ten years. Just to give you one specific example, I’ve been doing Donald Sutherland’s little three-toned whistle to myself for decades, usually without even realizing I’m doing it. For another example, I realized on this most recent re-watch that I still have a clear memory of every single song that plays over the P.A. system (“Tokyo shoe shine boy….”).

I was surprised how much of it I had held onto after all this time, although it won’t be a shock that the movie made much more of an impact on me now that I’m fully an adult. Though even at the time, I had a strong sense that this was different than a lot of films I had seen, as it turns out, a cynical condemnation of the Vietnam War isn’t something a twelve-year-old can fully appreciate.

But I can now. Although more than a few of its elements are rough around the edges fifty years later, the audacity of Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H still shines through. In fact, considering how toothless current Hollywood satire can be, much of it has aged even better.

M*A*S*H (1970)

Starring: Donald Sutherland, Elliot Gould, Tom Skerritt, Robert Duvall, Sally Kellerman

Directed by: Robert Altman

Written by: Ring Lardner Jr.

Length: 116 minutes

Released: January 25, 1970

One doesn’t summarize M*A*S*H so much as just provide its basic outline: Surgeons Hawkeye Pierce (Sutherland) and “Duke” Forrest (Skerritt) arrives in South Korea and drive to the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital via stolen military jeep. As they make it to their new station, we are introduced to many of the other people already stationed there: commanding officer Henry Blake (Roger Bowen) and his assistant “Radar” O’Reilly (Gary Burghoff!), dentist Walter “The Painless Pole” Waldowski (John Shuck), man of the cloth Father Mulcahy (a very young Rene Auberjonois) and antagonistic fellow surgeon Frank Burns (Duvall), to name just a few. Two crucial late arrivals include colorful chest cracker “Trapper John” (Gould) and new head nurse Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan (Kellerman).

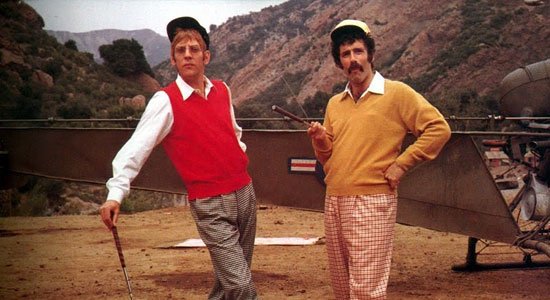

What happens in M*A*S*H? Well, the real answer is that, against this backdrop, Pierce, Duke and Trapper John mostly just kind of fuck around. They, like many men who got roped into an overseas war with a nebulous and unclear purpose, they spend their down time in Korea pulling pranks, harassing and sleeping with the few women there (including Jo Ann Pflug), and just…I dunno, playing golf?

That’s during downtime. When, it’s…uh…uptime, wounded and dying soldiers are brought in from the battlefield via helicopter and it’s time to get to work. Intercut through all the buffoonery are tactful-but-bloody scenes in the actual surgery room (or tent), where our characters now have to rely on their extensive training to make split-second decisions in order to patch up our armed forces.

Anarchy is the name of the game for M*A*S*H, both in terms of the characters’ attitudes to the cold chaos and injustice surrounding them, and in terms of how the film is structured. It isn’t traditionally plotted, with an A-B-C format. Instead, it kind of lopes along, moving from vignette to vignette until it abruptly concludes. This refusal of traditional format subsequently makes it a difficult movie to peg down completely.

It’s tempting to categorize M*A*S*H as a war movie or, perhaps more accurately, an anti-war movie. And this isn’t wrong. M*A*S*H is anti-war in the sense that the movie is more or less physically absent of war, as least as it’s usually presented in a Hollywood “war” film. None of our primary characters see combat, and they’re not really soldiers in the traditional sense. There is a major battle sequence to wrap up the film: a climactic football game shot like a war zone, complete with men getting hurt and collapsing to the ground.

However, bloody conflict is felt in other ways. As mentioned above, the members of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital are ultimately left responsible for the consequences of combat, saddled with the job of closing up the holes blown into the chests of men in a war being fought right in their backyards.

So, yes, it is anti-war, just not in the way we’re accustomed to. Compare M*A*S*H to something like Stanley Kubrick’s PATHS OF GLORY, an absolutely brilliant anti-war film where the injustice of war and how soldiers are expected to act against their own innate humanity is laid bare. However, we also know where Kubrick stands in regards to its message. To be infuriated, left with feelings of helplessness and desperation as these young men are led to their deaths at the hands of their own country for the crime of being scared…this is how Kubrick screams into the void. Through stark photography. Through Kirk Douglas’ masterful and steady performance.

But, M*A*S*H….doesn’t really leave you with any of that. Nobody gives a rousing monologue (in order to do that, they’d have to stop worrying if their erectile dysfunction makes them gay first), nobody verbally expresses their frustration or anxieties, nobody gnashes their teeth at their evil generals. The closest we get to something like that is the sequence in Japan, where they blackmail an annoying hospital commander by staging photos of him in bed with a hooker.

Otherwise, all of that interiority is expressed by the fucking around, the pranking, the harassment. For as strong leaders as Duke, Trapper and Hawkeye are when shit starts going down, they don’t really conduct themselves as noble defenders of liberty. In one of the biggest signs that opinion on American interventionism had taken a turn, their behavior is more akin to that of rowdy frat boys.

In this sense, maybe it’s best to describe MASH as an anti-Hollywood war film. Compared to more rah-rah films of the time (such as the movie that eventually beat it out for Best Picture, PATTON), Altman’s M*A*S*H may as well have been transported from a different planet. It’s an intentional, full-throated attack on what had come before; it’s no accident that many of the P.A. announcements throughout the film are advertisements for similar war films from around the time of the Korean War, their summaries and casts read with the same kind of nervous deadpan as one would when announcing the opening of a new latrine.

Now, given the description of individual scenes and moments above, it won’t shock you to hear that not everything about M*A*S*H has aged perfectly. It’s pretty blunt about gender and ethnic relations, the kind of movie whose soundtrack indicates the scene has changed to Japan by the banging of a gong. One of the only black characters with lines carries the nickname “Spearchucker”, with no apparent intended irony (in-universe, it’s because he used to throw javelins in high school, but come on). Strong women exist to be taken down a peg, to take the stick out of their ass.

Again, when put in context, the brazenness is the point and, to be honest, one of the most realistic things about M*A*S*H. Given the absence of anything else to do except patch up pawns in a pointless war, our characters blow off steam by being assholes. Funny assholes, but assholes nonetheless. Intense as it may be, it shouldn’t surprise you to learn that many related to this disillusionment in 1970 America.

Still, not all of it is handled with perfect grace. Maybe its most disappointing failure is in the depiction of Hot Lips Houlihan. Maybe the confusion as to the goal of this character as writ is aggravated by the fact that she’s played by Sally Kellerman, someone I’ve always found a little annoying (fire up a couple of her musical numbers from LOST HORIZON sometime if you disagree), putting her at a disadvantage in my heart and mind. But I think M*A*S*H the film fails her in the end.

It’s not so much that the horned-up, frustrated men surrounding her decide to take her down a peg simply for the crime of being a strong-willed woman in a war zone (again, this mostly reads as sadly realistic); it’s the fact that she becomes dumber and dumber as the movie goes on. During the infamous “shower scene” (where the curtains get pulled down, revealing her in her entirety to the entire squad) and her subsequent explosion at Blake, we both feel her exasperation, her frustration at the insanity that surrounds her (and we darkly laugh at Blake barely giving a shit, such is the male military machine).

From there? We never see that strong “head nurse” character again. By the time we get to that climactic football sequence, she’s a “blithering idiot” head cheerleader. Now, writing this all out, this sounds like an intentional shift, a consequence of being worn down by the hyper-masculine gears of war. But if that’s the case (and it may be!), it needed to be more apparent, at least for me. As it stands, her enthusiastically misunderstanding even the basic fundamentals of football as a sport feels like it’s meant to be genuinely funny. This may be a misread on my part.

Thankfully, the movie is bursting at the seams with iconic performances regardless. Donald Sutherland’s turn as Hawkeye has gotten swallowed up whole when Alan Alda’s version became essentially the only one in the public consciousness now. But he’s terrific here, playing him as a laid back observer of humanity. Once again, young Elliot Gould was a force to be reckoned with, and it’s no accident that the movie goes into another gear once Trapper John enters the fray. He’s anarchy personified, and he’s perfect.

As for Tom Skerritt, did anybody have a better knack for being in the most popular movies of all time? This, ALIEN, TOP GUN, STEEL MAGNOLIAS….though Duke may be the lesser of the three leads (and the only one not to be carried over to the TV show), he brings a nice cool-guy energy to perfectly balance out Sutherland and Gould.

Whether M*A*S*H is Altman’s best work is highly debatable. However, it might be the most indicative of his directorial trademarks, and a good early rubric for what to expect from his films going forward. All of that iconic overlapping, improvisational speech is in full force here, and it’s hard to imagine the film being any other way. What better way to effectively communicate the chaos under a MASH unit tent than everybody talking over each other?

(It should be noted the overlapping speech is also used for comedic effect, usually through Gary Burghoff’s Radar, who remains a half-second ahead of Major Burns’ orders.)

Of course, maybe the biggest ding to M*A*S*H ‘s legacy is the subsequent legacy of its spinoff project….uh… M*A*S*H, the CBS sitcom that ran for eleven years and cranked out a finale that to this day remains the single most watched episode of television in American history. For as much of a smash as MASH was in 1970, by the 80’s, the definitive versions of these characters had been cemented into the country’s consciousness.

I will say that the basic idea of M*A*S*H actually translates pretty well to episodic television (the movie is more or less structured like a bunch of episodes smashed together), but it’s always amused me how much Robert Altman hated and resented the TV show. He admitted as much in an out-of-nowhere moment on, of all things, a DVD commentary track. Whether or not he’s off-base, I’ll leave up to you. However, I always respect people who wake up extra early to be the best hater they can be.

Okay, one other thought re: the television series. We all know its theme, that somewhere-between-jaunty-and-somber instrumental melody line to “Suicide is Painless”. It’s classic, maybe the single most recognizable sitcom theme of its day. Re-watching the movie, however, made me remember that we get the full song and lyrics not once, but TWICE (once during the opening credits, and one at Painless’ “funeral”). And, folks, I was reminded that “Suicide is Painless” is one of the most nihilistic songs ever written.

The game of life is hard to play

I'm gonna lose it anyway

The losing card I'll someday lay

So this is all I have to saySuicide is painless

It brings on many changes

And I can take or leave it

If I pleaseThe sword of time will pierce our skins

It doesn't hurt when it begins

But as it works its way on in

The pain grows stronger, watch it grin

Woof. It’s very funny to me that this has managed to become a thirty-second jingle that everyone instantly recognizes from reruns. There’s a reason they left the lyrics off the opening TV credits.

All in all, M *A*S*H’s legacy was immediately secured, earning five Academy Award nominations, although it won only Best Adapted Screenplay. Fifty years on, I think it deserves more shine than it does now, eclipsed by a long-running sitcom and later, better work from its director. It’s an American satire so anarchic that it seems almost unbelievable it got made at the time, much less now.

Isn’t that worth a look?

Best of

Top Bags of 2019

This is a brief description of your featured post.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sign up with your email address to receive news and updates.