Recent Articles

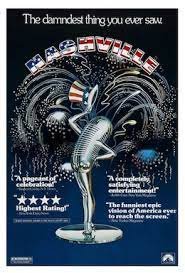

We Are The Story: Robert Altman Walks in NASHVILLE

This week, we complete our look back at Robert Altman’s work of the 1970’s with a deep dive into NASHVILLE, a sprawling panorama of the country music scene, of how we treat celebrity, of the intangible desire for change, of…well, practically everything, really.

As there must always be in every subculture across the Internet, there’s an ongoing discussion currently being held amongst the denizens of Film Twitter. This time around, it’s about the necessity of sex scenes in movies. I promise this is going somewhere.

Like many, I’ve been burned many a time by a sex scene popping up out of nowhere, usually when a parent or relative has just walked into the room (thanks, THE TERMINATOR!). And no doubt, there are many, many, many films and indeed entire genres that have sex scenes that exist only to (at best) titillate or (at worst) leer at a unsavory circumstance. However, I will mention that determining that kind of intent usually requires at least a little context, both onscreen and off, as well as some prior knowledge into the director’s prior work.

This is why a sincerely-held blanket “get rid of ‘em” philosophy gives me pause. Some are needed, some aren’t. And even if it’s not needed, I often think, who cares? Are jokes in film needed? Shouldn’t the characters stop being silly and just get to the point? But people joke in real life, so it becomes a movie thing. So it goes with sex.

As near as I can tell, a lot of the pushback on characters fucking is coming from intense old man voice Gen Z-ers on TikTok (Enjoy being blamed for everything for awhile, kiddos! We millennials had our turn). To some degree, then, this “discourse” can simply be chalked up to a lot of young people working out their feelings towards art, maybe for the first time, all against the backdrop of an increasingly complicated world. They’re just doing it on a never-ending public forum, something that a lot of us are extremely fortunate didn’t exist when we were in our teens and early twenties (a lot of my dog shit opinions are gone, nothing but so much internet dust now).

I also think the slow development over the past two decades of blockbusters becoming sexless, almost asexual, has pushed this topic to its boiling point. The FAST AND FURIOUS franchise serves as an almost too-perfect litmus test. Consider Dom and Letty, the defacto “main relationship” of the entire series (if you don’t count Tej and Roman), a couple that goes from grinding on each other in the first movie, 2001’s THE FAST AND THE FURIOUS, to barely touching by F9: THE FURIOUS SAGA. Whether this is a development of people being able to get their kicks and thrills for free from other media, or a consequence of film franchises now mostly being so many action figures being smashed together, I couldn’t quite tell you.

However (I’m arriving at “the point”!), others have identified a less obvious, but more consequential, source of sex scenes being considered by some as “unnecessary” to the plot of a given movie. It’s this: in a world where everything is “content”, anything that doesn’t move that “content” forward is thus anathema to enjoyment. In other words, the plot is now the thing. You can see this in action within, say, the MCU fan circles, where the multimedia franchise’s quickly-atrophying critical and popular acclaim over the past couple of years is getting explained away as the recent movies simply just “not moving the plot forward yet” (ignoring the fact that a few of them since AVENGERS: ENDGAME have just plain not been good movies).

This theory makes the most sense, at least to me. This mindset, if sincerely held by a significant amount of film fans (and in a world where exaggerating complaints to generate outrage, who knows if there’s truly a majority at play here), is a shame! On the one hand, yes, stories are what we ultimately go to the movies for. But stories come in so many forms, and can be told in so many different styles. A binary system of determining whether a story is “being moved forward” or not shields you from a bunch of different storytelling possibilities.

Case in point (see? “The point”! We’re here!), the story of 1975’s NASHVILLE is wide in scope and breadth, yet it’s told via tiny scenes that seems disconnected until they’re not. And often, the disconnect is sort of the point, too. Most scenes in it are explicitly not “moving the story forward” in a macro sense, yet when it’s all taken as a singular piece, not a single thread of the tapestry turns out to be out of place.

It’s an ambitious film, and one that is regularly considered Robert Altman’s magnum opus. Without having seen the entirety of his filmography, I’m still willing to go along with that, if only because of its wild confidence. There are so many characters and so many overlapping developments and movements that you’d expect it to collapse under its own weight, were it not for Altman’s light touch and almost audacious assurance.

More than anything, NASHVILLE shows that stories can be told any number of ways and be just as impactful in its totality than almost any film being made in the modern market. And that makes it worth a watch no matter who you are.

NASHVILLE (1975)

Directed by: Robert Altman

Starring: too many to count

Written by: Joan Tewkesbury

Released: June 11, 1975

Length: 160 minutes

What is NASHVILLE about? Well, there’s a short answer, and there’s a long answer.

In short, the film provides a snapshot (or maybe a panorama) of the beating heart of the titular city’s music industry, at least as it stood in the mid-seventies. A bevy of singer/songwriters and producers, some well-established, some who are aspiring, and some who have had better days, descend upon the Tennessee town in advance of an upcoming concert/fundraiser for Hal Walker, a rousing underdog Presidential candidate for the fictional Replacement Party (a candidate we hear a lot from but, tellingly, never actually see).

In long, though, it’s almost impossible to really illustrate what it’s “about” at first watch-through. The sheer scope of everything you see, of the criss-crossing storylines, of the absolute volume of characters at work here, and the way many of them disappear from the film juuuuust long enough to make you think maybe they’re not coming back, just in time for them to get a showcase scene….it’s probably best to just take it in the first time.

Oh, and NASHVILLE is also a de-facto musical, and one of significant heft. By someone else’s count, there’s about an hour’s worth of music (about a third of the film’s runtime), but it truly feels like a constant throughout. Infamously, many of the key songs (including the Oscar-winning “I’m Easy”) were written by the actors who sang them, something that apparently rubbed actual contemporary Nashville musicians the wrong way at the time. A fascinating New York Times article details the community’s reactions to the movie’s premiere in the real-life Nashville. There weren’t any riots or anything, but honest-to-god country superstars like Loretta Lynn seemed a little riled that actual country music artists weren’t used to develop the music.

Most of the time, I’d be on their side; a lot of the creative work (and the expertise to be found among it) has slowly been slid onto the plate of the onscreen performer, to the point that it seems most people assume everything is now improvised on set (seriously, fire up an episode of the OFFICE LADIES podcast sometime; 85% of the questions they get are some variation of “was [insert line or moment] improvised????”)

But, here’s the thing. I actually didn’t know the actors mostly wrote the music going in, and was a little shocked to learn it as a fact. It just all sounded like mostly legitimate country and bluegrass to my untrained ear. So, my sincere props, y’all! The New York Times article talks about how many of the lyrics were met by the country insiders in the audience with smirking recognition, perhaps indicating a level of parody at play here that mostly flew over my head. I just thought the music was actually good!

Another reason country stars, and thus Nashville proper, didn’t warm up to the film right away was this uneasy sense that they were being made fun of. After all, what is there to make of these exaggerated characters representing your home turf? Rumors also swirled that some of the major characters were one-to-one stand-ins for major current country stars which is, uhhhh somewhat true, actually; for instance, Barbara Jean is based on the aforementioned Lynn, Tom Frank (Keith Carradine) is based on Kris Kristofferson. Some characters were merely composites; Connie White (Karen Black) is a mix of Tammy Wynette, Dolly Parton and Lynn Anderson, while Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson) is a cross between Porter Wagoner, Roy Acuff and Hank Snow.

Naturally, Altman had always resisted this literal interpretation. To hear it from him, NASHVILLE is, if anything, a movie about Hollywood. This narrative framework was just set in Nashville mainly because of his growing affinity for the area. Although the film was mostly improvised on set, the standard modus operandi for Altman by this point, Joan Tewkesbury had provided the road map, filling up a diary of her notes, experiences and observations. Some of them made it directly from her pages to his film, most notably the freeway pile-up that begins crashing the characters together.

But the actual tapestry of NASHVILLE? The ecosystem of country music and the eccentrics that it attracts, all amidst this feeling of unseen, intangible hope, could just as easily be applied to the film scene in California. Or the theater scene in New York. Or a million other subcultures in this strange, bizarre, wonderful world we live in. Anyone who’s found a community through passion can recognize the archetypes at play; the fallen star, the up-and-comer, the knowing cad, the overzealous fan, the service man who wants to climb the ladder.

More to the point, NASHVILLE is so clearly about the American experience, both in broad and specific terms. It is both intensely of its time, yet unbelievably timeless. Hell, many of the key creatives behind this might be shocked (or appalled) at how relevant it all still is.

NASHVILLE is very much captured in 1975, in particular when considering how much shit had gone down in America the previous fifteen or so years. JFK, MLK, Malcolm X and RFK’s assassinations had all been in the past twelve years (something that is so clearly on this movie’s mind; more on that in a second), and the Watergate scandal earlier in the 70’s had done much to erode what was left of the population’s confidence in its government after the prolonged war in Vietnam.

A strong desire for change was in the air, although if NASHVILLE is to be taken at face value, there was skepticism that it was really going to be possible, at least not without a fight. As mentioned, Hal Walker, the reason the story of the movie is even happening, the speaker of many amazing and rousing platitudes….dramatically speaking, he’s a ghost. We never see him, his words just sort of float through the atmosphere. Everyone gathers for the mere possibility of change, even if we don’t know what it looks like.

A lot of NASHVILLE’s thesis statement can be gleaned from its pretty glorious opening scene, two songs being sung in completely different styles, recorded in completely different contexts, and sung by people of completely different races. One half of the scene is Hamilton attempting to record a very straight-laced and traditional Bicentennial song, a literally-titled “200 Years” (written by Hamlin and Richard Baskin). Its chorus refrains, proudly if a little naively “we must be doing something right to last 200 years!” It’s rousing, if staid to its core.

The other half, in another room within the same recording studio, is Linnea Reese (Lily Tomlin) and the all-black Jubilee Singers (from Fisk University, at the very least based off a very real choral group, although I couldn’t confirm if they were appearing as themselves here) laying down a rousing gospel track. As the piano joyously pounds, Linnea struggles to be heard over the voluminous sound behind her, asking over and over if we believe in Jesus.

Two completely different and unique styles, borne from diametrically opposed lived experiences and perspectives, living right next door to each other. That’s Nashville. That’s America.

******

It’s difficult to figure out exactly who to best highlight amongst NASHVILLE’s cast. There are so many moving pieces within its ensemble cast that you could probably watch the movie ten times and have a new favorite every single time. However, I’ll highlight a couple that took me by surprise.

Like many comedians from the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, I was primarily familiar with Lily Tomlin from her hosting stints on Saturday Night Live, although most people at the time probably knew her from ROWAN AND MARTIN’S LAUGH-IN. Folks nowadays likely know her from stuff like GRACE AND FRANKIE, a comedienne from previous generations that thankfully appears to be accepted and loved by younger generations (also known as the Catherine O’Hara Club). I hadn’t really ever seen her do a non-comedic role, however, although I had little doubt she’d be great.

She comes through! I think what really surprised me and made her stand out is that Linnea is so normal compared to both everyone else in the dang movie as well as every other character I’ve seen Tomlin play. She’s heartbreaking in her simplicity and nobility, a gospel singer that takes care of her two blind daughters, all the while being left unsatisfied by her husband (more on him in a second!). When she gets the chance to sleep with Tom, she can’t resist.

Linnea could be a really difficult character to sell to an audience, but Altman or somebody must have known that we were going to love her because she’s Lily Tomlin. They were right. One of the most unforgettable and memorable moments of NASHVILLE’s entire 160 minutes is her staring silently at Tom singing her “I’m Easy”. Maybe she knows she’s making a mistake, maybe not. All she knows is she’s doing something for her. She does all of us without a single written line of dialogue. I’m convinced she’s why the song won an Oscar.

If there’s a main backbone to the film, it’s probably the story of Barbara Jean’s recovery from a nervous breakdown. Ronee Blakely plays half of her scenes laid up in a wheelchair, but I found her entire arc pretty engaging, if only because it reminded me so much of how celebrities, especially women, tend to get squeezed from all ends until they collapse, sometimes emotionally and sometimes literally. Every aspect of her arc here happens publicly; her return, her collapse, her heartbreaking failed performance at Opryland (a scene so beautifully acted by Blakely, by the way, that I felt like I was watching a concert doc, not a narrative film), her violent death.

About the only thing she gets to do in private is recuperate. Even then, she gets to watch from her wheelchair as more glamorous performers take her now vacant slots, and she gets to observe her well-meaning manager/husband Barnett dismiss her anxieties as the beginnings of another nervous break. She never catches a break once in the film, but that’s how it goes for female celebrities throughout the past, present and future. We feel for them only when they’re finally at rest.

Barbara Baxley, star of both stage and screen, provided one of the other most memorable moments of the movie for me as Lady Pearl, the wife of Haven Hamilton. Midway through NASHVILLE, she gives this speech to Opal, a British reporter and our de-facto audience surrogate. Within this monologue, she talks about the reach John F. Kennedy Jr. had on areas of the country not previously thought possible, his subsequent assassination and. In doing so, she verbalizes and dramatizes the deep national tension at the time (and was still very much lingering in 1975) that NASHVILLE taps into so well:

And then comes Bobby. Oh, I worked for him […] he was a beautiful man. He was not much like John, you know. He was more puny-like. But all the time I was workin' for him, I was just so scared - inside, you know, just scared.

It’s here that the film starts to contextualize its ending. More on that in a second.

Finally, was there some sort of presidential order signed that mandated Ned Beatty appear in every single great American 70’s movie? This marks his third appearance on this blog in just under a year (including NETWORK and MIKEY AND NICKY). And, no surprise, he’s fucking great. You’re never going to believe it, but he plays an unsavory lush in this, although it’s notable that he never really does anything unsavory. He’s just not there for this saint of a woman he’s lucky enough to share a roof with. I’m a little shocked that Beatty only worked with Altman one more time (1999’s COOKIE’S FORTUNE). He’s a natural for the expository nature of his film set.

I could go on and on and on about every single character, and a real legitimate breakdown of this movie would almost have to in order to really dive into every nuance. You’d have to because these characters are the story. They are the plot, and the plot is them. Their human decisions affect the decisions of others. Or they don’t. Maybe their stories are purely internal. But that’s the story of humanity.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t talk about the ending, and why it’s so powerful in the midst of a world where just stepping outside can feel fraught with peril, where scanning the news invites you into a nightmarish hall of mirrors. In NASHVILLE’s final scene, as we finally reach the Hal Walker fundraiser, Barbara Jean gets assassinated on stage by a quiet, seething fan (a moment that seems eerily prophetic in the aftermath of Christina Grimmie’s 2017 murder, resulting in a world where stars like Taylor Swift have to walk around with what is essentially human Fix-a-Flat), and her limp body is immediately (albeit slowly) taken off the stage.

Amidst the shock, however, the indomitable human spirit endures. A new star takes the stage, and Hamilton urges the crowd to not give up, chillingly stating “we’re not Dallas!”. The entire crowd takes up in song.

It’s both ghoulish, bizarre yet simply moving. It’s America.

Although there is an uncharitable interpretation to be made of these final moments (a prediction of our current “the show must go on” culture that has essentially rotted our brains), I took it as perversely positive. For everything that this fucking country has had happen to it (and, of course, what it’s unleashed on others, both within and beyond its borders), we have a knack for moving forward anyway. Concerts endure. Sporting events endure. Beyond all reason, we still find political candidates to rally behind. We just kind of keep going.

Just, you know, try not to get too much blood on you while you do it.

*******

Not that it ultimately really matters, but Altman seemed to find his juice at the Academy Awards again after the success of M*A*S*H had thus far eluded him in the early to mid 70’s. NASHVILLE was nominated for five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. It lost both of those, although it must be said that this particular Oscar race was incredibly stacked. Its competition for Best Picture:

ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST (eventually won)

BARRY LYNDON

JAWS

DOG DAY AFTERNOON

Altman’s competition for Best Director:

Milos Forman (CUCKOO’S NEST, and eventual winner)

Federico Fellini (AMARCORD)

Stanley Kubrick (BARRY LYNDON)

Sidney Lumet (DOG DAY AFTERNOON)

What are ya gonna do? Altman had to settle for it being considered his magnum opus almost immediately, and probably his most enduring and popular film, besides maybe something like the aforementioned M*A*S*H*. Oh, and it still holds the record for most Golden Globe nominations for a single film, even all these years later. Not bad!

This brings me back to the “discourse” at the beginning of this article. By the same metric of “not ostensibly plot related = wasted calories” that leads to the very existence of sex scenes being questioned, NASHVILLE fails any possible equation you could run it through. Yet, do you want to live in a world where a movie like it could possibly be considered bad storytelling by any measurement?

Almost fifty years later, NASHVILLE remains an astounding achievement, both in scope and scale. It manages to reflect how stories can come from anywhere and everywhere. They surround us, both small and large. They are us. And there’s no “right way” to tell them. Let movies indulge! Let them take their time! Let them take you down oddball paths! The best ones have a way of enduring even when they’re weird.

That’s America.

Best of

Top Bags of 2019

This is a brief description of your featured post.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sign up with your email address to receive news and updates.