LOST IN TRANSLATION and The Power of Connection

One of the hardest questions for me to answer is “what’s your favorite movie?”

Responding to any variation of the “what’s your favorite ___?” inquiry is a daunting task, mostly because…well, nobody ever seems prepared to receive the almost infinite number of possible responses. There are always hidden right and wrong answers, but even the right answer can often be deemed wrong. For instance, say you asked someone “who’s your favorite musical artist?”, and they answered with “The Beatles”. It would be a technically appropriate answer (maybe even The Answer), but it would feel somewhat unsatisfying, right? Deep down, it feels a little too easy or something, doesn’t it? On the other hand, say they responded with a sincere “Imagine Dragons!”. You wouldn’t be able to hide your instantaneous eye roll, begging the question as to why you even asked in the first place if you were going to throw attitude at an “incorrect” answer.

It’s a piece of common communication that often breaks down before it even begins.

Because what we’re really looking for is something interesting, an answer that provides a little insight into the inner workings of the person being asked. You’re kinda hoping the question “who’s your favorite musical artist?” gets responded to with something like “King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard”. So the natural anxiety, at least for me, is the feeling that I have to come up with something cool when asked about my very favorite things.

Thus, when people ask “what’s your favorite movie?”, I’ll mention a range of candidates and maybe spit out one or two titles that mean something dear to me, both in terms of its content as well as its significance in a certain time of my life.

But when it comes to “Favorite Movie”, I stay away from defining it altogether. I have too much trouble communicating it.

Anyway, LOST IN TRANSLATION is my favorite movie.

Or at least it has been. Maybe it still is! All I can tell you is that it’s one of the very few movies that still conjures up the exact feelings I had the first time I ever saw it.

It was November of 2003, I was fifteen years old and my mom and I were knocking out movies that were starting to get awards buzz. It’s a process that caused me to see quite a few films that I enjoyed (ADAPTATION, SIDEWAYS) and many that ended up going in one ear and out the other (RIP to SEABISCUIT and MILLION DOLLAR BABY). LOST IN TRANSLATION was quickly becoming an indie darling that particular year, so we headed down to the Tower Theatre, one of the only two theaters in town that really played stuff like this. I didn’t walk into the theater with any preconceived notions. I mean, I liked Bill Murray from all the stuff a fifteen-year old boy would have seen him in (GHOSTBUSTERS, GROUNDHOG DAY), but I didn’t know Scarlett Johannson and I certainly didn’t know Sofia Coppola.

Oooh, boy, did that change.

I had never really seen a movie that…not spoke to me, exactly, but allowed me so totally to enter its dreamlike haze. Part of it was the soundtrack, part of it were the characters’ knacks for expressing entire lifetimes of thought without actually saying anything, part of it was just its specific color palette. I had never seen a movie that had so completely absorbed me. I’m not certain I’ve ever seen another.

And, man, for years afterwards, I just would not shut up about this movie, so attached I had become to its dreamy melancholy. If someone else mentioned it at school, I desperately wanted to slide into the conversation (and often did, much to their chagrin). I lamented THE RETURN OF THE KING’s historic Oscar sweep that year, if only because it came at the cost of mostly freezing out LOST IN TRANSLATION (at least in my mind; Coppola did walk away with a Best Original Screenplay trophy). The second it got released on home media, I chronicled my pursuits of finding a DVD that was specifically in widescreen on my LiveJournal. There are people I went to high school with who will text me to this day whenever the movie comes up in the course of their natural lives. To them, I say, thanks for bearing with me.

It may surprise you, then, to hear that I really didn’t revisit LOST IN TRANSLATION once I graduated high school. The thing of it is, once you reach your college years and beyond, you begin the process of slowly reappraising and revisiting things you used to enjoy. You dig up old episodes of your favorite cartoons. You pop on all the albums that shaped you. You fire up the movies that formed your tastes. And you often start noticing…hmmm, a lot of stuff I used to like was actually pretty bad! Turns out there’s no accounting for taste when you’re a toddler, and who the fuck knows what goes through your mind when you’re a teenager.

Because of this, I hesitated for well over a decade to revisit LOST IN TRANSLATION, because I just didn’t want to face the possibility that the reason it stirred me so was simply because I was a dumbass.

So there it sat. Until this week.

No, just kidding. I revisited it a couple of years ago first. Fuck, it would have been a way better story if I hadn’t, though, huh?

In February 2020 (yes, there really was a brief period of that year that vaguely resembled real life), the very same Tower Theatre that I had originally seen LOST IN TRANSLATION was doing a promotional event. Dubbed The Director’s Cup, it was a sort of March Madness bracket where eight different directors’ filmographies would be competing head-to-head against each other. Two movies would square off and be ran as a double feature over a weekend. You at home would get to vote for which director gets to move forward. So on and so on. They…uh….never got a chance to finish it.

Anyway, as a result, LOST IN TRANSLATION was playing in town to represent Sofia Coppola’s ouevre. Nervous as I was, I finally got to take my wife to see it how I saw it. This was it, the movie I had often talked about but never worked up the courage to actually pop in. In front of my spouse, no less, I was about to find out if my taste held up or not. And….

It held up. Of course it did. If anything, LOST IN TRANSLATION took on even more meaning now that I was an adult (we’ll get into it).

Now, it also revealed itself to be a movie with its own unique flaws, and we’ll talk about them as we get there. But it turns out there’s something universal about the feeling of disconnect, of being profoundly alone, and forging unexpected bonds in the middle of nowhere.

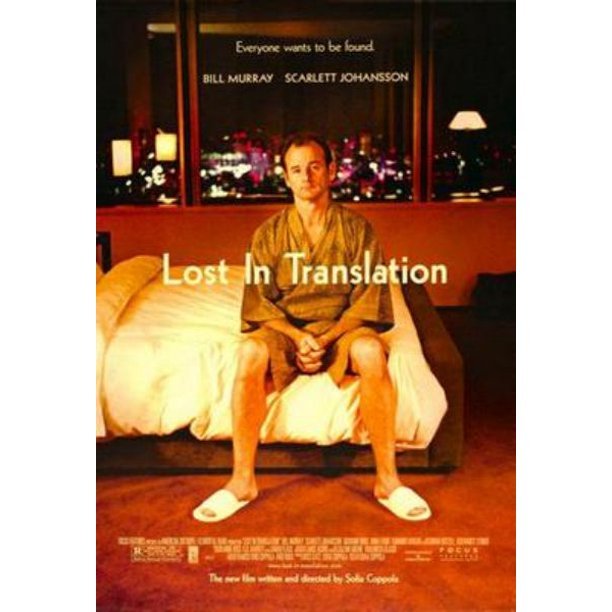

LOST IN TRANSLATION (2003)

Starring: Bill Murray, Scarlett Johannson, Fumihiro Hayashi, Giovanni Ribisi, Anna Faris

Directed by: Sofia Coppola

Written by: Sofia Coppola

Released: September 12, 2003

Length: 102 minutes

Bob Harris (Murray) is an American actor, one who has likely left his prime, who has arrived in Japan to shoot a series of Suntory Whiskey ads. He’s immediately and hopelessly out of his element; his translator has a habit of broadly summarizing the meticulous instructions being thrown at him, the hotel shower is much too small to accommodate him, and he can’t really adjust to the jet lag. His extensive travel is also clearly putting a strain on his marriage; his wife still needs him to pick out carpet samples, and she faxes him messages that come in the middle of the night.

Bob is a man who, in this particular moment, belongs nowhere.

Charlotte (Johansson) also happens to be staying in Tokyo, in the very same hotel in fact, as her rock photographer husband John (Ribisi) tours along with the band he’s currently working with. He’s sweet and well-intentioned, but neglectful in the way that only young career-oriented men can be. He’s always got somewhere to be so, most days, Charlotte’s left to wander the city alone. She’s far too young to be this disillusioned about her marriage and future, but here she is.

As any star-crossed people must, their paths soon intersect. Bob and Charlotte run into each other at the hotel bar, and they quickly spark up a friendship (or something deeper?) as it soon becomes clear that they are the only two people in the entire city, maybe the world, that they can actually communicate with.

What follows is what some people have uncharitably referred to as “nothing”. The body of the film is a series of events detailing the remainder of Bob and Charlotte’s stay in Tokyo. They spend a night on the town with some of Charlotte’s friends, as they hop from bar to karaoke bar. Bob reluctantly extends his trip for a few days in order to honor a booking on Japan’s version of “The Tonight Show”. Charlotte seeks something resembling spiritual awakening. They take a trip to the emergency room. Most of all, they both sit up at night and just…talk.

Again, not exactly what one would call the A to B to C method of screenwriting. But dismissing all of this as boring, as a not-insignificant amount of people seemed to do at the time, is an unfortunate way to dismiss what I would consider to be a very exciting and rousing film.

It’s through these vignettes that we learn so much about our two principals. More to the point, we learn just as much about them through their actions as we do through what they say. The stark differences in their demeanors when they’re together compared to when they’re apart. The way Bob’s malaise turns into joie de vivre. The way Charlotte suddenly seems able to articulate what she normally can’t even define to herself. That’s the movie in a nutshell.

Not to say that their words aren’t important. It struck me watching it this time around that Bob and Charlotte are both people who, despite them being at completely different points in their lives, find themselves in the same marital crossroad. They seem disillusioned, unsure of how they got here with their partner. It’s even interesting how their respective marriages kind of mirror each other; Bob is clearly the aloof partner in his marriage, similar to John in Charlotte’s.

All of this to say that this set-up leads to one of the more devastating exchanges in the whole film. During one of their middle-of-the-night talks, Charlotte bluntly asks Bob, “Does it get easier?” His reply: “No.”

He corrects himself, saying “yes, it gets easier”. But it’s too late.

This feeling of relief and honesty that Bob and Charlotte share with each other hits so nicely, not only because of the two astounding performances at the center of the narrative, but because Coppola so fully dramatizes their previous isolation within the first two minutes of screen time. Consider the first time we meet our central leads.

We can start with Bob, who is hazily sitting in the back of a taxi cab on the way from the hotel to the airport. He’s barely awake, and completely disoriented. The lights from the various billboards whiz by. Suddenly, as Death in Vegas’ “Girls” plays in the background, he sees it. One of his Suntory ads. The first thing he recognizes in this vast city he’s found himself in, and it’s a picture of himself, surrounding by Japanese type.

On the other hand, consider the first time we meet Charlotte. No, not the scene of her looking out the hotel window. It’s the famous first shot, a quietly framed shot of her rear end. It’s interesting to track people’s reaction to an opening like shot this, a desexualized picture of a private part. The first instinct I think anyone might have would be to giggle. However, the second is to get…a little uncomfortable, right? We’re used to shots of female body parts being depicted as sexual (consider that if the context were exactly the same, but with Bill Murray’s rear end, we’d likely know what to make of it more). But, in this instance? A female butt just…existing, as the opening credits roll?

So we just sit, slightly uncomfortable.

We’ve entered the characters’ headspace and it’s been thirty seconds.

———

The world of cinema has many examples of two unconnected people forging intense bonds due to random chance. BRIEF ENCOUNTER is probably the most famous, thanks to the heartbreaking performances of Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard, but also due to David Lean’s deceptively simple and efficient direction and the eloquent, Noel Coward inspired screenplay. It’s also not hard to make a connection between LOST IN TRANSLATION and Wong Kar-Wai’s international hit IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE, a similarly lush and devastatingly understated film about two accidentally connected people whose feelings cannot be fulfilled, released just three years earlier. Lest anyone think that movie wasn’t firmly in Sofia Coppola’s mind when she was putting LOST IN TRANSLATION together, consider that it appeared on her most recent Sight and Sound ballot.

However, there’s a key difference between the connections between Laura/Alec and Mrs. Chan/Mr. Chow compared to Bob and Charlotte. Bob and Charlotte is the one relationship out of those three that doesn’t feel explicitly romantic, or at the very least fueled by sexual desire.

The exact nature of Bob and Charlotte’s relationship is absolutely open to interpretation (it’s part of the beauty of Coppola’s creation) but to me, I’ve always read it as non-sexual, yet wildly intimate. Over the brief time that they share space with each other, these otherwise unrelated and unconnected people are almost quite literally soulmates.

Yeah, sex does enter the equation, in a roundabout way. A running joke about a lounge singer who warbles in the background throughout many of the scenes at the bar resolves with Bob sleeping with her. It comes to a head when Charlotte catches him with company the next morning. And, sure, it all makes things awkward for Charlotte (Johansson’s choice of expressing bemusement rather than shock in this moment has always fascinated me). However, it never feels like a matter of jealousy, at least not to me. It’s more like a bubble bursting, a reminder that this….whatever it is…has an inherent end date.

It can’t just be the Bob and Charlotte show forever.

This “soulmate” character dynamic is key for a couple of reasons. The primary one is that it assures that the significant and blatantly obvious age gap between the two leads never feels lecherous; for all the subsequent criticism levied against the film, I’ve never heard anybody ever accuse it of being “gross”. The second reason is that this difference is what ultimately gives this movie its power. It’s what gives it its universality.

Despite everything, humans are inherently social creatures. Even introverts (of which I consider myself one) can only isolate for so long before a desire to communicate arises; it’s why the Internet can be both a wonderful and dangerous place. I think there’s something more beautiful, then, about Bob and Charlotte’s respective yearning is just for someone to finally get them, rather than a desire to get into bed. Just my two cents.

———

Coppola has stated she drew much of her inspiration regarding Bob and Charlotte’s dynamics off of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall’s chemistry in THE BIG SLEEP. I found this sort of surprising at first, as those are humongous shoes to fill, and I wouldn’t exactly say it’s a one-to-one translation. However, viewed through this prism, I see what Coppola is going for. There’s an comfortable rhythm to Bogart and Bacall’s dialogue and interactions, maybe the best real-life couple to ever do it (there’s a reason THE BIG SLEEP instantly jumps up a few notches whenever the two are on screen).

Murray and Johansson are absolutely no Bogart and Bacall (who in the history of cinema ever was?), but that easygoing nature is totally there, and I think it helps fuel the storytelling so well. Again, when you think about the major theme of “communication”, it’s a good instinct to have our two leads be so at ease with each other after a few days (and maybe a lifetime) of not really being understood, either by others or by themselves. Why not draw inspiration from the most communicative screen couple in film history?

For their part, both Murray and Johansson are fucking revelatory here, perhaps the crowning achievement in two equally successful filmographies (in completely different directions). Though it’s pigeonholed her at times, Johansson’s power has long been her old soul, her ability to project lifetimes of experience beyond her years. Although she isn’t often doing much at all throughout the film, her world-weariness is so apparent from the jump. To that end, consider Scarlett is actually playing OLDER in this (Charlotte is supposed to be 22, Scarlett was 17 at the time of filming). Not everything she’s made between then and now has been brilliant, but there’s a reason why, unlike many of her costars, she’s unlikely to have suffered much from spending a decade in the Marvel machine.

On the other hand, the most jarring thing about Bill Murray’s portrayal of Bob Harris is how un-chatty his depiction of the character is. It’s so against type; Murray had made his career playing smarmy wise-asses on SNL before perfecting the formula in things like GHOSTBUSTERS, WHAT ABOUT BOB? and GROUNDHOG DAY. He’s mostly known now, I suspect, for kinda being an Internet meme, one of those guys who’s famous for being eccentric, although I suspect that’s a mostly self-promoted persona (and one that has its damages; we’ll get there).

Point being, his performance here seems to be this real turning point for him. It came off his career-pivoting work in Wes Anderson’s early stuff like RUSHMORE and THE ROYAL TENENBAUMS. Those were supporting roles; here, he’s front and center. Intense melancholy hangs on him just as well as detached sarcasm ever did. The relative lack of a full screenplay (the final document was apparently only 75 pages) also allowed for Murray to do what he does best: improvise and give little wisecracks. The “Roger Moore” photoshoot scene is one of those little “can’t see the acting” moments that are so rare in film, and it’s because of Murray.

I still think he was robbed of the Best Actor Oscar that year (as far as who did win that year? My only comment about Sean Penn in MYSTIC RIVER is that oftentimes acting awards interpret Best Acting as most acting).

———

It’d be disingenuous to talk about LOST IN TRANSLATION without diving its most common criticism, that of its “otherism” and “Orientalism” of Japanese people. However you may feel about it, it’s hard to deny that a large chunk of the movie hinges on the differences between our two leads and the people that surround them. In fact, Coppola wrings a lot of comedy out of it; an early shot of Bob towering over everybody in an elevator gives you an idea of what we’re talking about.

To be clear, this is not “woke mind virus” trying to re-evaluate a decades-old piece of work; charges of uncomfortable racism has dogged the movie since the week it came out. I distinctly remember people on internet forums banging this drum very early on in the movie’s run (including one person who ran a website called Lost In Racism, a name so hilariously blunt that I’ve never forgotten it). And in an era of heightened scrutiny and hate towards Asian-American communities, LOST IN TRANSLATION can admittedly be an uncomfortable watch at times. A not-insignificant amount of Bob and Charlotte’s banter revolve around the way Japanese people speak English. There’s a joke at a restaurant where every picture of the different specials are exactly the same. There’s at least two more “L and R” jokes than you probably remember.

Here’s the thing, though. Outside of a few instances that I’ll get into in a minute, I don’t know that the joke is often specifically on the people of Tokyo. In that elevator shot mentioned above, the interpretation “the movie thinks it’s funny that Japanese people are short” feels like a disingenuous read, at least to me. If anything, the joke is that Bob is different. He’s already a man out of place, and now he barely has anywhere to hide. We laugh due to his discomfort. At least I do (I’m not interested in altering art for the sake of accommodating for those who are laughing because “lol, Japanese are short"!” Fuck you. Stop watching movies.)

One of the bigger themes of the movie is an inability to communicate. Hell, the title is an obvious giveaway. Viewing the film through that frame, sequences like the commercial shoot become clearer in intent. The commercial director rapidly firing off long and eloquent acting notes to Bob, only for his translator to boil them down to a vaguer “more intensity”…it’s a good bit! And the scene isn’t trying to illustrate how crazy these Japanese people are, it’s driving home Bob’s isolation, how there isn’t one single person in his world at this moment that is able to talk to him, or for him to talk back to. Without these scenes, Charlotte and Bob’s stories intertwining wouldn’t have half the impact. The intent isn’t to offend, it’s to dramatize.

Now, that all being said….

Back in 2020, sitting there watching it in an actual theater, the only scene that truly landed with a thud was the “lip my stocking” sequence with the female sex worker. For context: an early scene shows a madam coming up to Bob’s room and giving him instructions that he doesn’t understand, including a command to rip her stocking. You can probably do the racist math from there.

It’s not that it doesn’t fit the movie, per se; it’s another example of a communication breakdown between Bob and a person in his space. The issue is that the joke of the scene truly does seem to be on her, the Japanese woman whose behavior is so crazy and weird, despite her being on her own home turf. To that end, this was the scene where you could sort of feel the 2020 theater audience get a little tense (for comparison, the scene received hearty laughter when I saw it back in 2003. Make of any of this what you will).

Everything else, though? Bob and Charlotte poking fun at everyone’s poor English? It sort of made sense to me within the confines of the characters’ situations at hand. To be clear, the characters making the occasional “L’s and R’s” jokes isn’t, like, great behavior or anything (and you could strongly argue it was irresponsible of Coppola to include such dialogue in the first place), and if people in real life were called out on this sort of thing, they’d hopefully feel pretty embarrassed. And the movie doesn’t really provide comeuppance or consequence for any of it, although I’d also argue it’s not obligated to, either, depiction not equaling endorsement and all that.

On the other hand….two outsiders talking shit to each other about their unfamiliar surrounds feels realistic to me. We all do it, even if it’s an uncomfortable thing to admit. I find it highly believable that two white Americans basically stranded in Tokyo with nobody else to talk to would begin rolling their eyes and saying, “why does everyone here talk funny?”. It’s not nice, but it’s a defense mechanism. It’s what people do.

Oh, and I guess another thing to address is the Bill Murray of it all. I grew up with Murray as a presence for as long as I can remember. He’s a guy who made his career off of being funny in front of a camera, but built his legacy off of cultivating eccentric stories about himself, some of which can sometimes sound a little too good to be true. There’s also a large chance that he’s just a genuine asshole; Geena Davis and Lucy Liu have both recently opened up about how poorly they got along with him on their respective sets, and he managed to get Aziz Ansari’s directorial debut scuttled by getting a sexual harassment complaint made against him. In isolation, one can rationalize any one of those things as “Bill being Bill” and retroactive judgment being made against him. On the other hand, it’s possible he’s just always been a dick and has successfully gotten us to look at it as just “funny troll” behavior. You’ll have to be the judge, but I felt like it should be mentioned regardless.

———

Back to what makes this movie such a treat.

First of all, we’ve talked a lot about Murray and Johansson, but there are other actors who shine in this. Fumihiro Hayashi almost walks away with the whole midsection of the film as “Charlie Brown”, a friend of Charlotte’s who adds some gleeful anarchic danger to their nights on the town (in a instance of life possibly imitating art, Hayashi is a friend of Coppola’s in real life). Giovanni Ribisi is perfectly cast as Charlotte’s aloof and flighty husband.

And, my favorite of all: Anna Faris makes a couple of brief, but important, appearances as Kelly, an American actress also in Toyko on a press junket. Her depiction of that superficially nice, yet completely vacuous celebrity is so perfectly realized that it’s been long rumored to be a spiteful caricature of Cameron Diaz, which has never really been confirmed or denied (I don’t really see it, FWIW).

I also think LOST IN TRANSLATION perfectly captures the hazy romance of travel, including the weird sensation of posting up in a hotel for days at a time (in some ways, it’s even stranger when it’s a nice place). I especially have always loved how the movie takes the time to show all aspects of Tokyo, both the big urban hubs and its smaller, more serene spiritual side, all without ever feeling like a corporate travelogue.

Finally, as will become a recurring theme in this series, I simply cannot wrap this up without talking about the soundtrack. I wouldn’t say LOST IN TRANSLATION has a score, per se. Every piece of music within it is a pre-existing song, although there are a handful of Kevin Shields songs that were written specifically for the film. But every track is chosen so thoughtfully in building the atmosphere and vibe (people have described the sound as “dreampop”; couldn’t have said it better myself). It’s a big reason why the movie made such an impression on me in the first place; the scene of everybody singing 80’s hits in the karaoke room was responsible for putting me on a New Wave kick for a while in my 20’s.

And when the final song in the final scene starts, as the opening riff to Jesus and Mary Chain’s “Just Like Honey” begins to play as our two leads separate, likely never to meet again…twenty years on, and I still get chills. And if you don’t, I don’t want to know you.

No, I’m kidding. It’s not that serious. I really love that moment, though.

———

This is silly, but I think about Bob and Charlotte a lot. I wonder how their respective marriages turned out, if Charlotte realized just how much goddamn life is ahead of her, and that she doesn’t need to play mistress to her husband’s occupation. I wonder how, or if, Bob navigates his starkly obvious midlife crisis. If he patches things up with his wife. If the whiskey ads were lucrative enough to have been worth it. Hell, I wonder if, in the advent of social media, Bob or Charlotte started chatting again or even braved figuring out a time and place to meet again after all these years.

It’s a movie I desperately wish could be given a follow-up, a BEFORE SUNSET-esque check-in on these two fascinating people. Yet I know that the very reason LOST IN TRANSLATION has any power at all is that it is an unresolved note. It’s a film that famously preserves its most cathartic moment (Bob’s final words to Charlotte) from its audience; Bob’s final words to Charlotte are whispered and rendered inaudible to us, a bold moment of dignity. They don’t know what happens next. And neither do we.

It’s a movie that gives you exactly as much as you need while leaving you wanting more.

I don’t think there’s a greater compliment I could pay a movie than that.